statler

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 7,938

- Reaction score

- 543

Yes, we speak of things that matter,

With words that must be said,

"Can analysis be worthwhile?"

"Is the theater really dead?"

Dangling Conversation - Simon & Garfunkel

Boston Globe - March 14, 2010

How to start an art revolution

A manifesto for Boston

By Dushko Petrovich | March 14, 2010

The recession has shaken many aspects of the American economy, and the art market is no exception. A world that had been flush with the ambition, energy, and freedom of a boom now finds itself in a serious crisis.

Funds are still wired from rich collectors to established galleries, but for working artists, especially young ones ? the as-yet anonymous talents who will shape the next phase America?s imaginative life ? a notoriously precarious vocation has become even less tenable. Many of the galleries that sell their work have collapsed; day jobs are harder to find, while studio rents and educational debts are still looming large. Within the art world, a once bullish and even rowdy scene has become decidedly more circumspect, its members nervously hoping ? some might say fantasizing ? that some good can come of hard times, that the market?s crash might give a new, more humane shape to the art world.

The wishful thinking and the practical solutions both tend to focus on New York, the center of the American art world, whose high-rent lifestyle and fast-paced market can be as deflating as they are seductive. Artists talk optimistically of changing the city, and they talk about fleeing to some cheaper, more isolated place ? upstate, maybe, or back to their hometowns. And they often wonder, sometimes out loud, if there isn?t another option ? somewhere that offers a similar richness of community and culture, at a safer distance from a demanding and capricious market.

It might sound strange to say it, but Boston could very well become that place.

The city isn?t exactly known for its boisterous and vital art scene, but Boston?s big cultural secret is that it has all the elements to build something genuinely important in the art world, and genuinely different. Boston could become the place where America?s most exciting young artists converge.

The city itself may not realize it yet, but if Boston took the initiative, if its political and cultural leaders got behind the idea, it could make itself into a real engine for the country?s creative life. The larger economic situation could actually be a moment of opportunity for the city, which has a rare chance to develop a new model for American artistic life. If that happened, it wouldn?t just benefit local artists and the art world ? it would be great for Boston as well.

For Boston to become a significant center for American art, we first have to admit that it is not one now. Puritan roots, bad weather, centuries of dominance by New York ? all these things and more have kept Boston from contributing to art in the outsized ways it has contributed to science, politics, or scholarship.

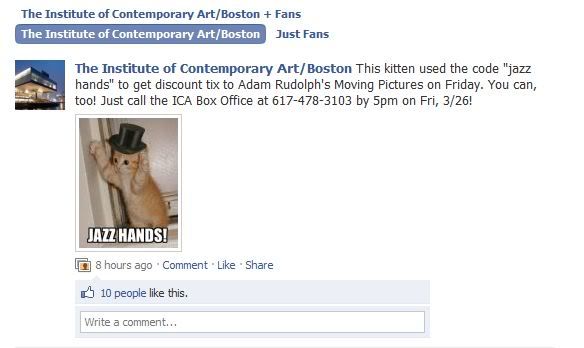

Today, Boston is known for producing a lot of art students, but not a lot of groundbreaking art. Dealers do OK business on Newbury Street or in the South End, but we?re sorely missing the handful of big, creative galleries that can make an art scene really thrive. The Institute of Contemporary Art is beautiful and beautifully placed, but it?s just finding its feet as a major institution and still exists in relative isolation from the daily life of the city. The many artist?s spaces and universities ? which do have public events like open studios, lectures, and exhibitions ? are dispersed by geography. The general consensus on Boston?s art scene is that it?s fragmented at the grassroots and too complacent at the institutional level. The most commonly heard complaint is that it?s sleepy.

Viewed from a slightly different angle, however, the local scene looks remarkably like a sleeping giant. Boston?s artistic resources are actually unparalleled for a city of its size: several great museums, a superabundance of universities, many galleries, a highly educated and increasingly sophisticated audience, and a density that allows for the most important element in cultural life: interaction between creative people. It will never be New York ? with its incomparable critical mass of money, museums, and media ? but Boston already has the infrastructure to build a valuable alternative.

That alternative would be a community more on a European model, where universities, museums, and other public institutions ? including the government, which can help with health care and rent stabilization ? combine to encourage a different, less market-dependent approach to creating art. Without ignoring the art market, Boston could position itself as a place to engage it more inventively, providing a much-needed haven for less commercial and more experimental work that pushes culture forward. Instead of (badly) imitating New York, Boston could provide a counterpoint: a well-considered sanctuary for artists to develop at a less frenzied pace, carefully harnessing the city?s wealth of tradition to the perennial strength of its youth.

Imagine a Boston where there weren?t just a handful of galleries in the South End and on Newbury Street, but shows were opening up all over ? in unused retail space, in loft apartments, in neighborhoods where people actually live. What if the ICA opened up a satellite branch in Somerville, or the Museum of Fine Arts increased access to its world-class archives, perhaps by displaying them in study centers around the city? What if Harvard established a fine arts degree, offering teaching positions to internationally known artists and providing their students warehouse studios in Allston? Picture an annual art fair that attracted top collectors and media to the Hynes convention center in search of emerging talents ? boosting the city?s economy and giving Bostonians a standing date with the global art elite. It?s not hard to envision how a dynamic new art scene would have benefits beyond art ? it could enliven whole neighborhoods, improve the city?s economy, even transform its outlook and place in the world.

This might sound like a radical departure for Boston, but in fact the idea of an art haven draws on our region?s deep tradition of deliberately created artists colonies. Early in the last century, many prominent artists ? George Bellows and Edward Hopper among them ? came to New England not just for its picturesque views and peaceful communities, but also for its intellectual and spiritual camaraderie. Artists colonies in places like Old Lyme and Cos Cob, Conn., and Ogunquit and Monhegan, Maine, provided sanctuary from the pressures and customs of the commercial centers, offering instead a community in which to engage and redefine the leading movements of the age. Their seaside views and bucolic scenes might look tame to our eyes, but in their willingness to apply the breakthroughs of 19th-century European painting to the visual facts of American life, those mild pictures actually laid the groundwork for a very vibrant century in American art. Their living arrangements also look pretty mild in retrospect, but those unconventional communities ? which emphasized creative interchange and solitude over status and commerce ? could serve as inspiration for a more sustainable, and more productive, local artistic life.

New England is still rich in artists colonies. The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the Vermont Studio Center, and MIT are just a few of the institutions that offer updated (and more temporary) versions of the older communities. But the much-expanded nature of the contemporary art world calls for something more organized and ambitious. In order to carry on this important tradition in a way that has a real and lasting impact, the region needs to innovate on a much larger scale.

So what would it take transform the artistic life of the city? With so many moving pieces, it will require more than a single gesture, but a good starting point would be the universities. With globally recognized names and campuses that span the Charles, they?re capable of attracting talent from anywhere, and even in straitened circumstances, they?re huge landowners and major investors in local communities.

Harvard University alone could make a big difference. Just by establishing a graduate program in fine arts, Harvard could immediately create ripple effects benefiting both the university and the city around it. For a relatively small investment, the university could convert some of its holdings in Allston into a program that would bring in world-class artists (with their ambitious students), make better use of its soon-to-be-unified museum system, and put the school on par with Yale and Columbia universities, which already have highly influential masters of fine arts programs. This would not only transform a neighborhood and raise the cultural profile of the school, it would be exactly the kind of gesture that could rouse the city?s other players into action.

Boston?s other universities and art schools teach so many of the nation?s emerging artists that another obvious priority would have to be keeping them here after they graduate. Some programs are already in place. For several years, Boston University has been hosting an annual large-scale art show ? the Boston Young Contemporaries ? to showcase the region?s outstanding new master?s graduates. Northeastern University has a new initiative that links curatorial students with art students, who work together to put up temporary exhibitions around the city. These moves are helpful, but they only begin to address young artists? two biggest problems: debt and rent. One step would be to pair these exhibitions with prizes ? a year?s workspace and stipend, for example ? that would reward promising artists for staying in the city.

A bolder initiative ? one that would set a useful and very provocative precedent ? would be for local universities to eliminate debt from advanced degrees in the arts. Rather than consider the master of fine arts a pay-as-you-go professional degree (like law or medicine), it could be treated as one of the humanities, like history or literature, where the university funds the education of accepted candidates, whose research furthers its larger mission. This move would obviously require significant initial investment, but the city?s universities would benefit doubly: by immediately attracting a larger (and better) pool of students, who would then go on graduate unshackled by loans, ready to start making impact in their field.

As for rent, one could imagine a program where universities worked together with the city and local museums to establish a network of post-graduate residencies for their outstanding students. Space could be found near existing institutions, in underdeveloped areas already owned by the schools, or in retail spaces currently left empty.

The ICA would also have a role to play. The museum recently jumped into the big leagues with its dramatic waterfront building and a series of marquee shows by international artists, but unfortunately, the building?s location also isolates it from the neighborhoods where people live and work. The ICA already does conventional outreach ? in the form of concerts, readings, and screenings ? but what about something less conventional? What if one of the universities helped the ICA secure a satellite location in a cheaper neighborhood, the way New York?s Museum of Modern Art runs the dynamic P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens? Imagine ICA Lower Allston. Or, for that matter, imagine a small network of museum/academic centers in edge neighborhoods, like the Fogg East Somerville and the Gardner Mission Hill, each with a university affiliation and a few prestigious fellowships for artists or curators. The payoff could be new exhibitions, classes for the community, and fresh and unexpected work from all corners of the city.

Riskier shows at noncommercial centers would provide a launch pad for younger artists ? giving them an audience and a way to start making a living with their work ? and would also put much-needed pressure on the city?s galleries to refresh their own programming, taking full advantage of the local talent and energetically trying to expand their audience, rather than merely playing to the tastes of established buyers. The popularity of the First Fridays event in the South End suggests that Boston?s public has a real appetite for galleries adopting a creative, open-door approach instead of the traditional, business-like one.

As Boston?s gravity increased, attracting more talent and civic pride, it would exert more pull on other regional powerhouses. New England already includes two of the nation?s most important art schools ? RISD, in Providence, and Yale, in New Haven ? along with many smaller but esteemed programs like those at Bennington and Hampshire colleges and Brandeis University. Traditionally, graduates of these schools head straight for New York to start their careers, but as the city?s energy grows, Boston will look increasingly attractive. Artists who come to (or stay in) Boston for places like the MFA and Harvard will, in turn, help enliven those same institutions, continually rousing the city?s vast collections from their intermittent slumber, ensuring that our accumulated treasures don?t stagnate.

Of course, much of what makes an art scene vibrant and important is intangible and totally impossible to mandate. We can?t summon the forward-looking collectors, or issue a casting call for big personalities, much less rally the sundry and sensitive critics, the networks of friends, the countless idiosyncratic details that any decent art scene needs to thrive. What we can do is recognize the opportunity and lay the groundwork for something that nobody else is yet doing.

It is also hard to describe precisely what would follow. Much has been written about the economic benefits of artistic institutions, but less attention is paid to the unquantifiable contribution that art itself makes to a city. Yes, there would be more street traffic, more customers, and less crime in neighborhoods with lively new galleries or resident artists, but there would also be more reflection, more discussion, more laughter ? more feeling.

The space Boston could occupy is one that doesn?t exist yet in America. The biggest art markets will always be in New York or Los Angeles, because that?s where the money and collectors are. The more interesting question for Boston is, where will the artists be? For artists, especially early-career artists who innovate and invent, Boston could really become a place to stay and develop. And that would benefit both American artists ? who can bring their work to maturity outside the often brutal commercial pressures of Manhattan ? and the city, which would reap both the material and the immaterial benefits of art.

Dushko Petrovich, a painter and critic, teaches at Boston University and is the founding editor of Paper Monument.

This piece focuses on fine art, but I think performance art should be included in the conversation as well.

.