Charlesview Keeps the Faith

By Andreae Downs

Globe Correspondent / August 10, 2008

They are preachers and teachers, but in the brouhaha over the future of the Charlesview Apartments, they've mostly been listeners.

"We have been listening and trying to be as sensitive as possible to the concerns raised," said the Rev. Samuel Johnson, pastor of the Community United Methodist Church and chairman of the Charlesview board of trustees.

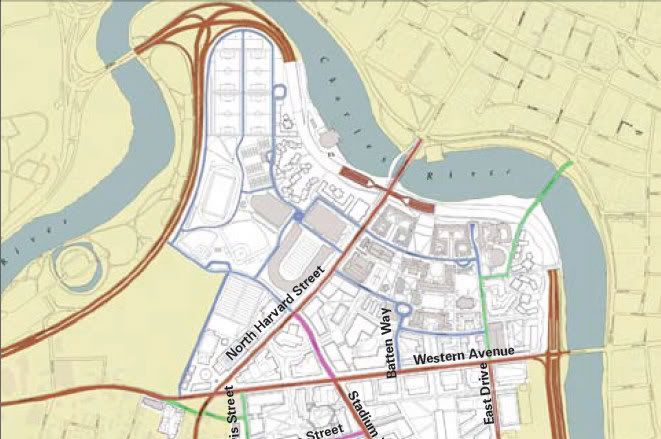

At issue are plans to raze the 213 Charlesview units at Barry's Corner and replace them with 400 apartments in the Brighton Mills area, where the land was obtained in a swap with Harvard University. The proposal has come under fire from neighborhood activist groups, which want shorter buildings, more open space, and better retail options.

But the trustees on the Charlesview board, created four decades ago from five mainline congregations to manage the apartments, say they represent a large, and less vocal, part of the community - the members of their congregations, as well as current and former residents of the Charlesview. And they're working with the developer, Community Builders Inc., to make sure their principles are being upheld.

According to Lawrence Fiorentino, a Barry's Corner neighbor and chairman of the board's development committee, "a lot of residents of Allston are former tenants of Charlesview." He added: "Everyone I've talked to on the board and in the community is excited about what is going to happen with Charlesview. Most feel it will be a jewel in the North Allston community."

For these constituents, density isn't a bad word.

Community Builders representative Felicia Jacques points to the new project's community center, increased retail offerings, and energy efficiency - which could include an energy cogeneration plant that requires density - as reasons why the structures will be an asset to the community. The board also wants to increase affordable housing options.

More to the point, Charlesview residents say, the current buildings are crumbling, and they need a decent place to live - fast.

"The walls are melting," said Raisa Shapiro, a tenant at Charlesview since 1990. The structure now is leaky, Shapiro said, and "large mice" are standard - more so since Harvard broke ground on its science center across the street.

"All my relatives are engineers," Shapiro said, "and they say, 'Run away! That's not safe!' "

Jacques said, "The physical plant at the existing Charlesview isn't safe in the longer term," which she put at three years.

Before construction can begin, however, many details remain to be worked out.

The proposal before the Boston Redevelopment Authority would be on 6.9 acres and include a 10-story building near the Charles River. At least one neighborhood group has suggested that the complex be spread out over an additional 13 Harvard-owned acres to reduce density.

In April, the BRA issued a "scoping" document that lists things the developer needs to address. It included recommendations to reduce density and make buildings shorter - more like surrounding properties.

"We are quite pleased with the BRA scoping," Johnson said. "We feel they support us and what we're doing." But, he noted, the trustees still want 400 units and, despite the calls for lower density, can't make plans to build on property they don't control.

Community Builders hopes to have an answer to the BRA suggestions by next month, allowing construction to start next year, Jacques said.

Activists say that to do that, the developer would have to ignore a big part of the scoping, which asks that the project take into account the BRA-sponsored communitywide planning process.

In general, the more vocal neighborhood activists say, the trustees leave too much of the planning to the developer. "We've reached out to all the congregations, and they've said their hands are tied, that Community Builders runs the show," said Tim McHale of Litchfield Street.

Controversy is nothing new to the Charlesview. In the early 1960s, the BRA had condemned the 9.3 acres of Barry's Corner - 4.5 acres of which house the current complex - as "blighted." The agency, fresh from flattening the West End, proposed razing the neighborhood of mostly single-, two-, and three-family homes and building a 10-story, 372-unit luxury apartment complex.

The resulting skirmish was recorded in William Marchione's book, "Allston-Brighton in Transition: From Cattle Town to Streetcar Suburb."

Paul Berkeley of the Allston Civic Association was in his 20s.

"I saw people dragged from their homes in handcuffs by the police, hundreds of people screaming and shouting; then a moving truck backed up to the house, emptied it, and then a bulldozer would come and knock it down," he said recently. That was when he decided to get involved in neighborhood affairs.

At about the same time, Fiorentino's mother, Josephine, was thinking Barry's Corner could use sprucing up. But the idea hatched at her Allston kitchen table - and shared by neighborhood activist Joseph Smith (now memorialized in the name of a local health center) - was for an affordable housing complex.

Fiorentino and Smith brought the idea to the monsignor of St. Anthony's, their parish, according to Lawrence Fiorentino. "At the time, houses of worship were the centers of community," he said.

The parish priest reached out to neighboring congregations for support, and after Methodist and Modern Orthodox congregations signed on, the group netted a $5,000 planning grant. Eventually, they persuaded the city to buy into the idea. In 1971, the Charlesview garnered a $5 million federally backed mortgage.

"Charlesview emerged as a kind of compromise," Marchione said in a recent interview.

Fiorentino knows of at least two original tenants who still live at the Charlesview. By the management company's estimates, about 40 percent of the tenants have been in place more than a decade.

Through consolidations over the years, the five original congregations have merged into three: St. Anthony's, Community United, and Congregation Kadimah-Toras Moshe. They serve about 1,300 people, or roughly 85 percent of the neighborhood.

But some things haven't changed over the years.

"What's amazing is how the five different congregations are still in lockstep," Fiorentino said. "The causes we champion are the same; the ways we go about that are the same."

Link