Joe_Schmoe

Active Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 374

- Reaction score

- 0

This month I?m going to feature someone somewhat less well known, but one that I really love?Boston granite style and Gridley Fox Bryant. If I could have my way, everything would be Boston granite style. It?s the only architectural style that has a city?s name in it and you?d think that for this reason alone, more architects designing in Boston would somehow incorporate it into their designs. Alas, I guess that granite is now too expensive to use in construction. Funny how when we were a poor country and built things by hand we could build with granite, but now that we?re a rich country and build with machines, it?s too expensive.

The oldest surviving building by Bryant in Boston is the Charles Street jail.

The old jail has seen better times, but hopefully the ongoing renovation will leave it no worse for wear. What?s worse is how the jail now seems cut off from the rest of the world by Storrow Drive, the MGH T station, Mass General hospital, and the Mass eye and ear infirmary. Surely these structures could have had more respect for their venerable neighbor. The new Mass General hospital wing seems to have made an effort in this direction by using greyish glass to match the grey granite of the jail, but it still looks to be turning its back to the jail and isolating it.

Coincidentally, I was taking a walk and I came across this building, right in the middle of a neighborhood:

I thought it looked a lot like the Charles street jail, and sure enough, a nearby plaque indicated it was indeed designed by Bryant. It is the Cambridge poor farm, where the destitute (and insane) were sent to labor. It was actually quite progressive in its day.

Bryant went on to design the amazing granite wharf buildings on the waterfront.

Commercial block was supposedly a major influence on H.H. Richardson, which you can see in his later commercial buildings:

Mercantile Wharf.

Mercantile Wharf was basically cut in half by the central artery. Can you imagine how impressive it must have been when it was twice as long as it is now?

The last of Bryant?s surviving great warehouses is the State Street block.

One of the things I love about Boston granite style is how the granite is not polished or smoothed in any way. It is left rough and textured.

Architecture has been smooth and sleek for what, 90 years now? When is some young architect going to get bored and sick of smooth and sleek and be truly cutting edge by rediscovering texture in building materials? Imagine what the Long Wharf Marriott, or Cobb?s Moakely courthouse, or City Hall for that matter, would have looked like, if they has used granite instead?

State Street block was also dismembered by the central artery. Here is what it looked like when it was whole, and when the water came right up to it

The less said about the new condos the better.

Although architecturally unexciting, I do kinda like how the new additions sit on top of the block like birds hitching a ride on the back of a great whale. I go back and forth on whether it would be better off to have its original mansard in place.

Around 1860, Bryant got into French Second Empire style in a big way. Here are his commercial buildings on Franklin Street on the site of Bullfinch?s Tontine Crescent:

Supposedly, Bryant helped his frequent collaborator Arthur Gilman with the layout of the Back Bay. Bryant designed the first three of the new houses on Arlington St. There are three separate houses here, but the structure has the unity of one large mass. Condo developers today could learn a thing or two from this about having unity without monotony.

Bryant and Gilman also worked together on these townhouses on Commonwealth Ave:

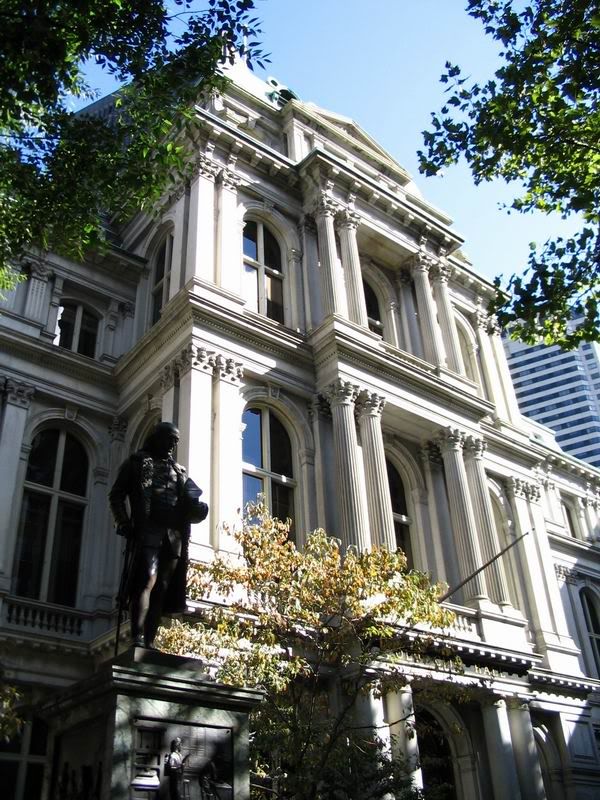

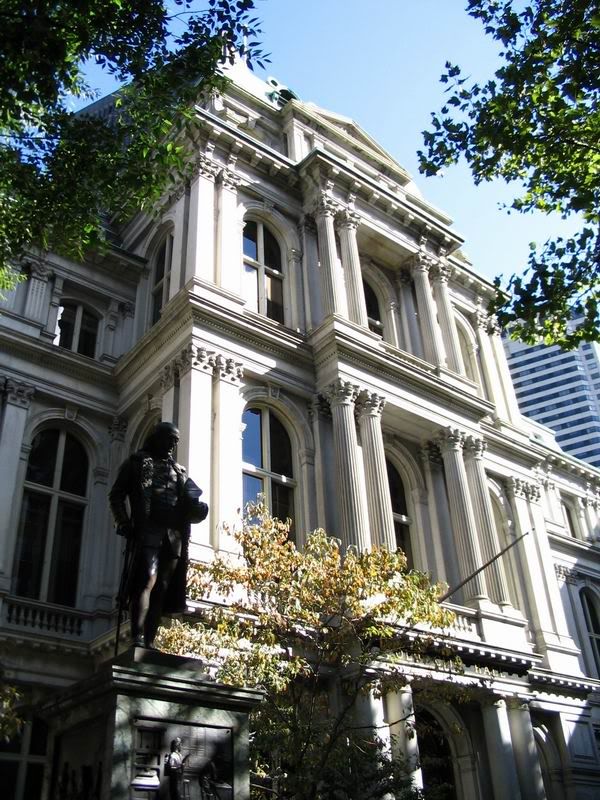

They also collaborated on this obscure building. I think it used to be a government building or something

Probably, Bryant?s greatest overall architectural composition was Boston City hospital, where Bryant designed the entire campus:

At its center was this absolutely terrific administration building.

Although some of the original structures remain, they are all overwhelmed by cold unsympathetic modernist buildings by Hugh Stubbins. The administration building was lost altogether.

All in all, Bryant designed probably close to 200 buildings in Boston, 150 or so of which were located downtown.

The thought of all of downtown Boston made of granite and French Second Empire structures is mind-boggling. It would surely be one of the country?s greatest architectural districts if it still existed as it did. However, a little thing called the great fire of 1872 destroyed 150 of Bryant?s buildings located downtown, including this one, the Cathedral Building, located at the corner of Franklin and Devonshire Streets.

Despite, the loss, Bryant heroically redesigned over a hundred of his destroyed buildings, such as the Transcript building.

However, most of these have again been lost to subsequent development such as Merchants National Bank Building, formerly located at 28 State Street

As you can tell from the tone of this months entry, one of my favorite things about Boston is the old granite warehouses and commercial buildings. I?ll end this thread with Bryant?s Horticultural hall, which used to sit on Tremont Street across from the Granary burrying ground.

The oldest surviving building by Bryant in Boston is the Charles Street jail.

The old jail has seen better times, but hopefully the ongoing renovation will leave it no worse for wear. What?s worse is how the jail now seems cut off from the rest of the world by Storrow Drive, the MGH T station, Mass General hospital, and the Mass eye and ear infirmary. Surely these structures could have had more respect for their venerable neighbor. The new Mass General hospital wing seems to have made an effort in this direction by using greyish glass to match the grey granite of the jail, but it still looks to be turning its back to the jail and isolating it.

Coincidentally, I was taking a walk and I came across this building, right in the middle of a neighborhood:

I thought it looked a lot like the Charles street jail, and sure enough, a nearby plaque indicated it was indeed designed by Bryant. It is the Cambridge poor farm, where the destitute (and insane) were sent to labor. It was actually quite progressive in its day.

Bryant went on to design the amazing granite wharf buildings on the waterfront.

Commercial block was supposedly a major influence on H.H. Richardson, which you can see in his later commercial buildings:

Mercantile Wharf.

Mercantile Wharf was basically cut in half by the central artery. Can you imagine how impressive it must have been when it was twice as long as it is now?

The last of Bryant?s surviving great warehouses is the State Street block.

One of the things I love about Boston granite style is how the granite is not polished or smoothed in any way. It is left rough and textured.

Architecture has been smooth and sleek for what, 90 years now? When is some young architect going to get bored and sick of smooth and sleek and be truly cutting edge by rediscovering texture in building materials? Imagine what the Long Wharf Marriott, or Cobb?s Moakely courthouse, or City Hall for that matter, would have looked like, if they has used granite instead?

State Street block was also dismembered by the central artery. Here is what it looked like when it was whole, and when the water came right up to it

The less said about the new condos the better.

Although architecturally unexciting, I do kinda like how the new additions sit on top of the block like birds hitching a ride on the back of a great whale. I go back and forth on whether it would be better off to have its original mansard in place.

Around 1860, Bryant got into French Second Empire style in a big way. Here are his commercial buildings on Franklin Street on the site of Bullfinch?s Tontine Crescent:

Supposedly, Bryant helped his frequent collaborator Arthur Gilman with the layout of the Back Bay. Bryant designed the first three of the new houses on Arlington St. There are three separate houses here, but the structure has the unity of one large mass. Condo developers today could learn a thing or two from this about having unity without monotony.

Bryant and Gilman also worked together on these townhouses on Commonwealth Ave:

They also collaborated on this obscure building. I think it used to be a government building or something

Probably, Bryant?s greatest overall architectural composition was Boston City hospital, where Bryant designed the entire campus:

At its center was this absolutely terrific administration building.

Although some of the original structures remain, they are all overwhelmed by cold unsympathetic modernist buildings by Hugh Stubbins. The administration building was lost altogether.

All in all, Bryant designed probably close to 200 buildings in Boston, 150 or so of which were located downtown.

The thought of all of downtown Boston made of granite and French Second Empire structures is mind-boggling. It would surely be one of the country?s greatest architectural districts if it still existed as it did. However, a little thing called the great fire of 1872 destroyed 150 of Bryant?s buildings located downtown, including this one, the Cathedral Building, located at the corner of Franklin and Devonshire Streets.

Despite, the loss, Bryant heroically redesigned over a hundred of his destroyed buildings, such as the Transcript building.

However, most of these have again been lost to subsequent development such as Merchants National Bank Building, formerly located at 28 State Street

As you can tell from the tone of this months entry, one of my favorite things about Boston is the old granite warehouses and commercial buildings. I?ll end this thread with Bryant?s Horticultural hall, which used to sit on Tremont Street across from the Granary burrying ground.