JimboJones

Active Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2007

- Messages

- 935

- Reaction score

- 1

Not sure if anyone would find this interesting, but w/e!

Source: Ancient Italian Abodes Spur An Unlikely Real Estate Boom - By Rosamaria Mancini, The Wall Street Journal

In Puglia, at the heel of the Italian boot, a centuries-old architectural peculiarity has turned into an unlikely real-estate boom.

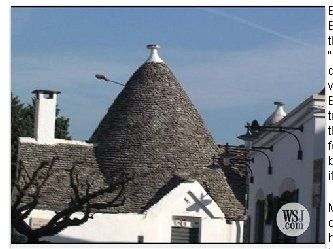

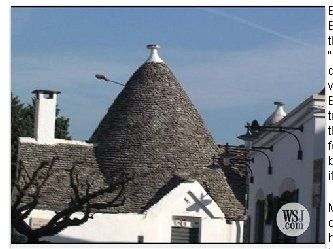

To the locals, the trulli -- the cone-roofed structures that dot the countryside -- are a reminder of the region's humble past. The most basic trulli are one-room, round huts constructed of stacked, dry stones, which form walls and a simple vaulted cone roof. They date back to as early as the 14th century, and most housed peasants or livestock -- or both. Dimensions are snug: The average cone is slightly bigger than a four-person camping tent. Many lack necessities, such as running water or toilets.

Trulli, quirky structures in Southern Italy that once housed peasants and livestock, sparks an unlikely real estate boom.

But to a growing number of British, Dutch and Germans, they are the ideal fixer-upper. "Our kids thought we were crazy," says Stephen Snooks, who moved from Derby, England, to a 300-year-old trullo (from the Greek troulos or tholos, meaning dome) about four years ago. "They couldn't believe we were going to live in it."

Mr. Snooks first saw a picture of a trullo on the Internet, then headed to Puglia with his wife to see what they were all about. To them the trullo was romantic, it was steeped in history and it was a property they could fix up. It reminded them of the cone-shaped coast houses in the English countryside that were used for drying hops for beer. They also fell in love with the region and the simple way of life they could have in Puglia, where people still take siestas in the afternoons and Sundays are for relaxing.

They laid down a deposit on a five-cone trullo -- each room has its own cone-shaped roof -- on about two acres that cost a total of ?57,000 ($85,570). Three months later they moved to the small town of Martina Franca and lived out of their camper while they gave the trullo a thorough cleaning and installed a bathroom. "I thought, 'I need my bloody kitchen,' " says Mr. Snooks's wife, Jo Waters, but after sinking another ?30,000 into renovations after moving in, she says she got used to life in a trullo. The renovations included connecting a power line for electricity, and repairing the pump for a rainwater tank to provide water for the bathroom. (They bring in bottled drinking water.) They also added appliances to the kitchen and painted inside and out.

There are about 5,000 trulli in various states of disrepair scattered among the olive groves and prickly pear cacti in the Valle d'Itria, on the strip of land flanked by the Adriatic and the Ionian seas. Stone was plentiful in the area, and according to local legend, the trulli were built without mortar so they could be quickly disassembled into a pile of bricks when the tax collector came. About 1,400 of them are located in the town of Alberobello, designated a Unesco World Heritage site because of the structures.

During the 20th century, the trulli were abandoned by their owners, who fled to the city in search of modern conveniences. Some were used as occasional country homes by locals, while some of the larger ones were turned into rustic country inns or restaurants.

Then, foreigners started coming. About five years ago, low-cost carriers, such as Ryanair, began ferrying people to nearby Bari from Frankfurt and London. Visitors were intrigued by the oddly shaped structures, many with Christian or astrological symbols painted on their roofs.

Sensing opportunity, local real-estate firms started advertising in British magazines, and pushing the trullo as a unique country-home investment. Pietro D'Amico, who owns a local property firm, says he sold 200 trulli to British buyers last year, a 10% increase from the year before.

The recent trulli boom is partly a continuation of the foreign-fueled real-estate speculation that began in Tuscany several decades ago, where so many British began buying second homes that it was given the nickname Chiantishire. As the values of country homes in Tuscany soared, the more adventurous wandered into nearby regions such as Umbria, and then farther south to the Marche and Abruzzo, buying up abandoned farmhouses or run-down villas. Puglia is the end of the line.

"These are properties that are still affordable, in spite of the soaring real-estate prices in Italy," says Lucia Bruno, an architect whose company helps restore trulli.

While a trullo might be cheaper than a Tuscan farmhouse, prices have risen in recent years. Today, unrestored trulli with three cones go for around ?80,000, an increase of about 30% from five years ago, according to Mr. D'Amico. The cost of fixing one up has also surged. Adding the basics -- bathroom, kitchen and electricity -- can cost at least another ?80,000, he says.

Gregory Snegoff, of California, was living in Rome for several years but grew tired of its big-city chaos and, along with his wife, decided to move to the country. The actor/director first learned about Puglia and its trulli from friends. He initially rented a trullo and then decided to buy one in the small town of Ceglie Messapica, where they have lived for four years.

"For us, it's wonderful," says Mr. Snegoff, who bought a one-cone trullo and another small structure, which sit on six acres, for ?25,000. "We are interested in a self-sustaining way of life where we can eat the fruit and vegetables we grow and enjoy the peace and tranquility of the country."

As more foreigners have bought trulli, businesses have popped up to service them. Ms. Bruno, who is from Turin and now lives in a restored trullo powered by solar panels, heads a small firm called Trullishire (after Tuscany's Chiantishire) which tries to help foreigners find qualified local craftsmen and offers assistance in navigating the thicket of red tape that comes with restoring a trullo. Trulli have to be restored in accordance with strict building-code and planning regulations, which can be a tangled bureaucratic process. Common requests that are denied include enlarging or adding to the trulli's small windows, or adding sunrooms or expansions using wood or terra cotta.

There are a few new trulli owners who have pushed the envelope, turning what was once a humble abode into a luxury residence. Ms. Bruno is handling the construction management of a five-bedroom, three-bathroom trullo, with an underfloor heating system powered by solar energy, for a London resident. It will also feature a 16 ?-foot-by-26?-foot in-ground pool. The owner paid ?90,000 for the trullo but is spending ?300,000 on the restoration and expansion, says Ms. Bruno. It took more than a year and several revisions of plans to get a building permit, Ms. Bruno says.

Source: Ancient Italian Abodes Spur An Unlikely Real Estate Boom - By Rosamaria Mancini, The Wall Street Journal