This is a rare case where I somewhat sympathize with the NIMBYs. This area has no capacity for increased trip generation on any mode other than walking and biking, and those modes will continue to be unpleasant alternatives for non-local trips until the bridge is replaced and/or Sullivan Square gets nuked from orbit.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

BHA Charlestown/Bunker Hill Redevelopment | Charlestown

- Thread starter Scipio

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

This is a rare case where I somewhat sympathize with the NIMBYs. This area has no capacity for increased trip generation on any mode other than walking and biking, and those modes will continue to be unpleasant alternatives for non-local trips until the bridge is replaced and/or Sullivan Square gets nuked from orbit.

Exactly. It's so easy being an misinformed individual to just say, let's build this and think that it is a great improvement from their viewpoints and not consider the genuine negative impact it will have on the people that actually live there. To those individuals, stick with city simulators because that's not how real life works.

Traffic problems aren't going to change if you hold up a development or 20. That's the part that people are struggling with. I think too many activists have some vague hope from some of the comments I've read that if we can only defeat all projects traffic will somehow ease. It won't. You're going to be stuck in traffic in this city from 6AM to 2AM. That's not going to change no matter how many more residential buildings go up or how many get blocked.

Of course transit should be improved, but think of this: Wouldn't having more people in the city particularly new residents actually increase the chances for transit improvements as more and more people demand it? As opposed to having only long time residents here who are used to the MBTA's deficiencies.

Of course transit should be improved, but think of this: Wouldn't having more people in the city particularly new residents actually increase the chances for transit improvements as more and more people demand it? As opposed to having only long time residents here who are used to the MBTA's deficiencies.

odurandina

Senior Member

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2015

- Messages

- 5,328

- Reaction score

- 265

Seattle and SF are spending tens of billions on transit.

Massachusetts is spending its money on Mass Health and bloated public unions.

the day they passed Mass Health, the first thing i thought of was all the doomed air rights projects, and affordable units.....

no, srsly......

Massachusetts is spending its money on Mass Health and bloated public unions.

the day they passed Mass Health, the first thing i thought of was all the doomed air rights projects, and affordable units.....

no, srsly......

- Joined

- Sep 15, 2010

- Messages

- 8,894

- Reaction score

- 271

Seattle and SF are spending tens of billions on transit.

Massachusetts is spending its money on Mass Health and bloated public unions.

the day they passed Mass Health, the first thing i thought of was all the doomed air rights projects, and affordable units.....

no, srsly......

I know I'm the first to craw when we go off topic, but srsly, check your priorities.

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

Odd way to view it. Traffic problems aren't going to change if you hold up development, that's correct, but it will exacerbate if development goes through without improving the existing infrastructure.Traffic problems aren't going to change if you hold up a development or 20.

Another weird way to think of the issue. It can be changed and waiting until the problem gets worse is how we ended up with the Big Dig. In other word, shortsighted planning and the idea of holding off improvement in infrastructure will end up coming back to haunt the city later. Residents are requesting to at least maintain the status quo but the city should be looking for ways to alleviate the issue. Again, residents' worries would most likely be assuaged when improvements are made (such as the plan to upgrade the Charlestown bridge with a dedicated bus lane). Until then, the issues raised by the residents are legitimate and deserve to be heard.That's the part that people are struggling with. I think too many activists have some vague hope from some of the comments I've read that if we can only defeat all projects traffic will somehow ease. It won't. You're going to be stuck in traffic in this city from 6AM to 2AM. That's not going to change no matter how many more residential buildings go up or how many get blocked.

This line of thinking is completely out of order and is shortsighted. The improvement should come before not after, otherwise you end up having the same situation as the Seaport where you are building up without the necessary infrastructure to support it. This line of thinking is how Los Angeles was built.Of course transit should be improved, but think of this: Wouldn't having more people in the city particularly new residents actually increase the chances for transit improvements as more and more people demand it? As opposed to having only long time residents here who are used to the MBTA's deficiencies.

By the way, please note that this is not just isolated to infrastructures related to traffic. This includes schools, fire stations, police stations, etc. In regards to schools, increasing the density of Charlestown without expanding school facilities will reduce the quality of education for Charlestown residents who are low-income and have limited resource to make up for it.

Kent, you're imaging a world that doesn't exist. That's cool, and I hear ya, but I'm trying to ground this in the reality that we live in for the foreseeable future.

Traffic problems will have no discernible change with these developments. You'll be stuck in traffic regardless. I'd also say that even with improved transit, traffic will never get better until flying cars are invented. I'm not saying that doesn't suck, but it is what it is. An upgrade to the Charlestown bridge sounds good. Dedicated bus lane? Sure. Will that make much of a difference? I'm skeptical.

But your idea of how the city should do all these improvements before people start moving in sounds great and I'm completely on board. Do you have any examples in the last half century of any major city actually doing so? Yes, they should. But asking taxpayers to spend money now for the benefit of potential future residents isn't something that will happen politically because people won't vote to do that. Blame the voters, society, etc but that kind of forward thinking just doesn't exist.

What does exist is an increasing # of people demanding an improvement. More people in the city = more people relying on transit because of existing gridlock = more pressure to improve transit system. Simple supply and demand when you boil it down. Since we can expect little to no federal money as long as the Trumpster is around, only a critical mass of voter engagement because they have a personal involvement will get the city/state off their butts. That starts with having more and more troops on your side by increasing the housing supply.

Traffic problems will have no discernible change with these developments. You'll be stuck in traffic regardless. I'd also say that even with improved transit, traffic will never get better until flying cars are invented. I'm not saying that doesn't suck, but it is what it is. An upgrade to the Charlestown bridge sounds good. Dedicated bus lane? Sure. Will that make much of a difference? I'm skeptical.

But your idea of how the city should do all these improvements before people start moving in sounds great and I'm completely on board. Do you have any examples in the last half century of any major city actually doing so? Yes, they should. But asking taxpayers to spend money now for the benefit of potential future residents isn't something that will happen politically because people won't vote to do that. Blame the voters, society, etc but that kind of forward thinking just doesn't exist.

What does exist is an increasing # of people demanding an improvement. More people in the city = more people relying on transit because of existing gridlock = more pressure to improve transit system. Simple supply and demand when you boil it down. Since we can expect little to no federal money as long as the Trumpster is around, only a critical mass of voter engagement because they have a personal involvement will get the city/state off their butts. That starts with having more and more troops on your side by increasing the housing supply.

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

Yes, Somerville. Assembly Station on the orange line.But your idea of how the city should do all these improvements before people start moving in sounds great and I'm completely on board. Do you have any examples in the last half century of any major city actually doing so?

Wouldn't enabling the ~1.2 million daily commuters to the city to live within city limits actually reduce traffic? Boston is too dependent on commuters for an old city that wasn't planned to accommodate cars.

No, because more people are going to move in regardless. Also many people in cars are doing so because they have to (taking a trip, transporting large/heavy stuff, work in a place with no transit, etc) or are already carpooling/ubering/busing/etc which we all like to see but still clog the roads.

Think of any growing city in the US. Has any city reduced gridlock with the exception of ones that have experienced a massive population loss?

The funny thing is I agree with a lot of the opinions expressed here about how it would be nice if certain things could be done. At the risk of offending the Thread Police, the N/S Rail Link is a great example of a project I'm 100% on board with in terms of what it does, but believe by the time the funding comes through the Transporter from Star Trek will already be up and running.

Likewise, in major cities there is no longer a way to avoid gridlock. People are moving to Boston to chase jobs, and if you're stuck with the choice of no gridlock/no work or gridlock/paying job - most people will chose the second one. What Boston needs to do is grow and grow and grow and have that increasing amount of people demand better transit options. Politically the bigger you are the more attention you get in a representative democracy. Embrace growth as a tool to improve transit not because that's the best way to do it, but because its the most likely way. The second part of that is to throw in the towel on the traffic, which isn't the same thing as liking it. Only depopulation will fix that and not too many people are advocating that.

Yes, Somerville. Assembly Station on the orange line.

Huh. what does everybody say Somerville traffic is a disaster then?

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

Huh. what does everybody say Somerville traffic is a disaster then?

It didn't get worse. It would have gotten significantly worse if you let Assembly Row build out and have everyone in that neighborhood take their cars into the city instead of taking the Orange Line. You keep thinking the goal is to completely wipe out traffic issue. The goal is to not exacerbate it or limit it. I said it each time in each of my posts.

odurandina

Senior Member

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2015

- Messages

- 5,328

- Reaction score

- 265

Boston is getting to be huge by Boston standards.

For you youngin's, it beats the crap out of 1970.

For you youngin's, it beats the crap out of 1970.

It didn't get worse. It would have gotten significantly worse if you let Assembly Row build out and have everyone in that neighborhood take their cars into the city instead of taking the Orange Line. You keep thinking the goal is to completely wipe out traffic issue. The goal is to not exacerbate it or limit it. I said it each time in each of my posts.

Why wouldn't they just go to Wellington?

Regardless, I've never said that people are expecting to completely wipe out traffic. You've sorta made the same point I did which is Somerville traffic is no better having opened that new Orange line. How much worse it could have been is tough to measure. I do stand by though that for the Charlestown situation, and many more like it, we need boots on the ground to press the transportation issue. I just don't see a situation where people are going to pony up ahead of time for potential new residents. As assbackward as it may be to both of us, the way the system works is an ever increasing amount of people will demand and eventually get due to sheer numbers transit improvements. You get an ever increasing amount of people by increasing the housing supply. If we don't any pittance of dollars we may be getting from the feds will instead be going to build yet another highway in places like Houston. The city needs to grow, first and foremost to act as a catalyst for all the improvement both you and I would like to see. I'd also point out more residents = increased tax revenue = more state/city funds for transit.

fattony

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2013

- Messages

- 2,099

- Reaction score

- 482

I think Rover is right here. There are fundamental difference between road traffic and transit and there are fundamental reasons that we don't see transit precede development.

First, traffic:

If you increase the capacity of a roadway, the traffic on it will expand to fill the available capacity. Individuals have a certain tolerance for using their time (waiting in traffic) to pay for "free" resources (like roads). If the "free" resource is tightly constrained, only the people willing to pay the most (i.e. wait the longest in traffic) will get the resource. There are literally millions of people within 20-30 miles of Boston who can and will clog the roads given enough capacity.

People can travel fast and comfortably on un-congested "free" roads until they approach the inner core and start "paying" by waiting in traffic. The price mechanism used to simultaneously satisfy supply and demand on roads is time spent sitting in traffic, but the pool of potential drivers is effectively infinite because un-congested roads are essentially free. Since our pool of potential drivers is infinite, a marginal increase to that pool is still infinite. The demand curve doesn't move just because you make a tiny % increase to the pool of potential drivers. That is why building more housing doesn't change the amount of traffic, although it may change WHO is in traffic. The people who are presently in traffic are actually scared that someone else will take their spot in traffic. The traffic doesn't actually get worse.

Second, regarding trains to nowhere:

Transit works similarly, but fundamentally differently from roads. Using transit also comes with a price in the form of time spent getting to transit and time spent on transit. Different from roads, however, the potential catchment of a transit stop ends a certain walking distance from the stop. There is no walking equivalent of the "free ride" offered by un-congested roads which connect distant homes to congested roads. You don't add potential riders by adding sidewalk capacity, haha.

To add potential transit riders, you have to build homes within walking distance of a stop - that is, homes near transit create new people with a low cost (in time) of using transit. If you build transit to an area with no population or low population density and very few people can walk to it, you've built transit only for people with a high cost of using it (a long walk). That is why building a train to nowhere is politically infeasible. You need homes and transit in conjunction for the transit to work. In contrast, the homes "work" on their own to the extent that people buy/rent them despite the lack of transit.

Politicians don't and probably shouldn't allocate millions or billions to projects that server no one (yet).

First, traffic:

If you increase the capacity of a roadway, the traffic on it will expand to fill the available capacity. Individuals have a certain tolerance for using their time (waiting in traffic) to pay for "free" resources (like roads). If the "free" resource is tightly constrained, only the people willing to pay the most (i.e. wait the longest in traffic) will get the resource. There are literally millions of people within 20-30 miles of Boston who can and will clog the roads given enough capacity.

People can travel fast and comfortably on un-congested "free" roads until they approach the inner core and start "paying" by waiting in traffic. The price mechanism used to simultaneously satisfy supply and demand on roads is time spent sitting in traffic, but the pool of potential drivers is effectively infinite because un-congested roads are essentially free. Since our pool of potential drivers is infinite, a marginal increase to that pool is still infinite. The demand curve doesn't move just because you make a tiny % increase to the pool of potential drivers. That is why building more housing doesn't change the amount of traffic, although it may change WHO is in traffic. The people who are presently in traffic are actually scared that someone else will take their spot in traffic. The traffic doesn't actually get worse.

Second, regarding trains to nowhere:

Transit works similarly, but fundamentally differently from roads. Using transit also comes with a price in the form of time spent getting to transit and time spent on transit. Different from roads, however, the potential catchment of a transit stop ends a certain walking distance from the stop. There is no walking equivalent of the "free ride" offered by un-congested roads which connect distant homes to congested roads. You don't add potential riders by adding sidewalk capacity, haha.

To add potential transit riders, you have to build homes within walking distance of a stop - that is, homes near transit create new people with a low cost (in time) of using transit. If you build transit to an area with no population or low population density and very few people can walk to it, you've built transit only for people with a high cost of using it (a long walk). That is why building a train to nowhere is politically infeasible. You need homes and transit in conjunction for the transit to work. In contrast, the homes "work" on their own to the extent that people buy/rent them despite the lack of transit.

Politicians don't and probably shouldn't allocate millions or billions to projects that server no one (yet).

- Joined

- Sep 15, 2010

- Messages

- 8,894

- Reaction score

- 271

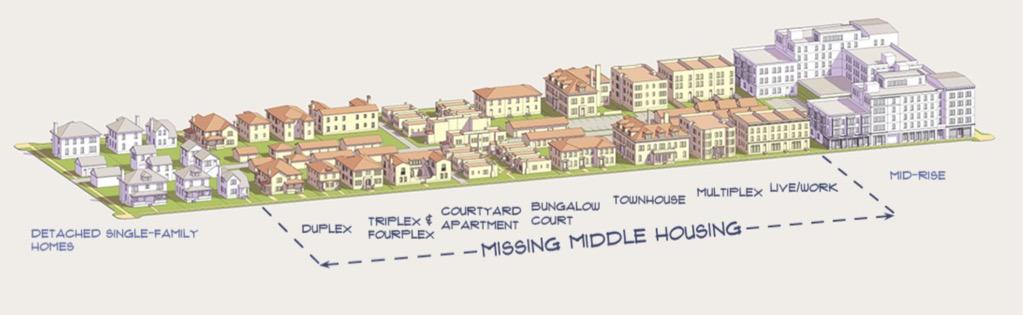

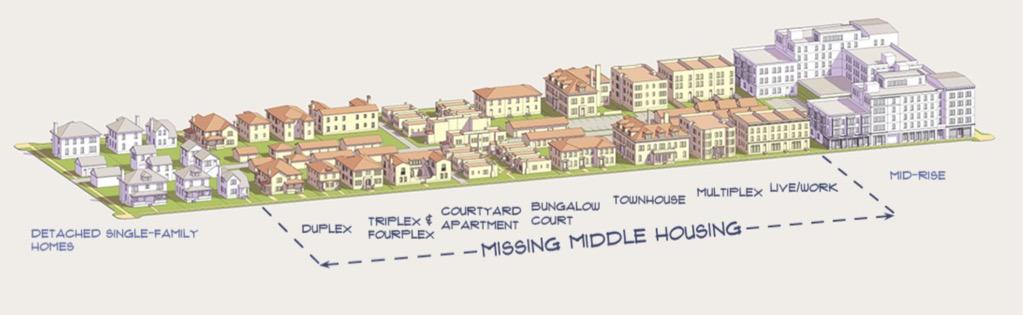

This situation is the perfect case for gentle density ("the missing middle" housing style)

Read this thread for more info: https://twitter.com/BrentToderian/status/874109206164512768

"Gentle Density" in Copenhagen:

Read this thread for more info: https://twitter.com/BrentToderian/status/874109206164512768

"Gentle Density" in Copenhagen:

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

Fattony, this is true, but the scenario you are describing is different than the one that Charlestown is facing. As mentioned earlier, the idea is to add a dedicated bus lane through through Charlestown and into Haymarket This proposal still constrains traffic but speeds up traffic for public transportation only.First, traffic:

If you increase the capacity of a roadway, the traffic on it will expand to fill the available capacity. Individuals have a certain tolerance for using their time (waiting in traffic) to pay for "free" resources (like roads). If the "free" resource is tightly constrained, only the people willing to pay the most (i.e. wait the longest in traffic) will get the resource. There are literally millions of people within 20-30 miles of Boston who can and will clog the roads given enough capacity.

Second, please read my original post. The issue with the bus that runs through Charlestown is that they come relatively infrequently through the neighborhood, particularly the 93 which runs by the area affect. On the weekday, this is due to traffic which results in bus grouping/bunching. What's the point of running more buses when they end up grouping into caravans which comes every 20 minutes instead of what it is supposed to be, which is 7 minutes. A dedicated bus line would resolve this issue. On weekends, they come by every 20-40 minutes. Considering the area is made up of low income residents who DON'T work the typical 9-5 job, having to compete with thousands of new residents on a weekend for a bus that comes once or thrice every hour can a problem, especially if a bus is full and they have to wait another 20-40 minutes to get out of the town. A simple solution is the have the MBTA run additional buses. This is something that shouldn't be too hard to negotiate but one that needs to be done.

People can travel fast and comfortably on un-congested "free" roads until they approach the inner core and start "paying" by waiting in traffic. The price mechanism used to simultaneously satisfy supply and demand on roads is time spent sitting in traffic, but the pool of potential drivers is effectively infinite because un-congested roads are essentially free. Since our pool of potential drivers is infinite, a marginal increase to that pool is still infinite. The demand curve doesn't move just because you make a tiny % increase to the pool of potential drivers. That is why building more housing doesn't change the amount of traffic, although it may change WHO is in traffic. The people who are presently in traffic are actually scared that someone else will take their spot in traffic. The traffic doesn't actually get worse.

Again, nothing to do with the issue in Charlestown. Read my original post. Charlestown is an under-served neighborhood, public transit-wise. Sure, the new higher income residents have the option to drive or take public transit, however, the many of the existing low income residents don't. Their only option is to try to get on over-crowded buses. As a long-time ex residents of Charlestown, there were many cases, especially during the winter, where, I having to wait at the last few stops before it gets to downtown, had to wait for 3 buses before being able to get on a bus. Imagine having to compete with thousands of new residents that choose to not take their car into the city. The issue of traffic is that it exacerbates the problem by causing buses to bunch up. A bus dedicated lane + more frequent bus services would resolve the issue.

Methinks you have never been to Charlestown. There's a lot of residents in the neighborhood. This isn't some location like the Seaport that is being built from scratch. That being said, the MBTA decided to shift the Orange Line path (which used to run through Main Street), to where the highway is, serving only a miniscule portion of the residents in Charlestown and none of the area in question. That is because, while relatively close, Charlestown is divided by a hill that runs through the middle of the town, making it more difficult for residents in this part of the town to reach Community College/Sullivan Square station.Second, regarding trains to nowhere:

Transit works similarly, but fundamentally differently from roads. Using transit also comes with a price in the form of time spent getting to transit and time spent on transit. Different from roads, however, the potential catchment of a transit stop ends a certain walking distance from the stop. There is no walking equivalent of the "free ride" offered by un-congested roads which connect distant homes to congested roads. You don't add potential riders by adding sidewalk capacity, haha.

To add potential transit riders, you have to build homes within walking distance of a stop - that is, homes near transit create new people with a low cost (in time) of using transit. If you build transit to an area with no population or low population density and very few people can walk to it, you've built transit only for people with a high cost of using it (a long walk). That is why building a train to nowhere is politically infeasible. You need homes and transit in conjunction for the transit to work. In contrast, the homes "work" on their own to the extent that people buy/rent them despite the lack of transit.

Politicians don't and probably shouldn't allocate millions or billions to projects that server no one (yet).

This is incorrect. Again, look at the example of Assembly Station. Prior to the announcement that the Orange Line was looking to add a station here, there were no residents at Assembly Row. The location had a mall, a movie theater, Circuit City, Home Deport, and Good Times Arcade. The area was served by two buses, the 90 and 92, and rather infrequently. The addition of the Assembly Station, spurred the development, as it was built in conjunction with Assembly Row. The same needs to be applied here, especially since Charlestown is significantly larger than Assembly Row.I think Rover is right here. There are fundamental difference between road traffic and transit and there are fundamental reasons that we don't see transit precede development.

Last edited:

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

Why wouldn't they just go to Wellington?

Look at a map of where Assembly Row is located and where Wellington Station is located and let me know how residents can get over there without the use of a car.

We can look at another example as a control. Let's look at the new Wynn casino considering this development is being built without the infrastructure needed to support it. The comparison is somewhat similar since both Assembly Row and Wynn Casino has a destination aspect to it and as we all know, studies conducted on the Wynn Casino has stated that traffic in the area would worsen. So yes I can say with confidence that it could have been worse without the new train station.Regardless, I've never said that people are expecting to completely wipe out traffic. You've sorta made the same point I did which is Somerville traffic is no better having opened that new Orange line. How much worse it could have been is tough to measure.

Then don't allow development. How can residents trust that the city will eventually improve the area when there are so many examples where promised transit improvement didn't come into fruition? The Silver Line in the Seaport, the Green Line extension, the Arboway restoration, Blue Line extension to Lynn. Have the improvement come with the development like they did with Assembly Row.I do stand by though that for the Charlestown situation, and many more like it, we need boots on the ground to press the transportation issue. I just don't see a situation where people are going to pony up ahead of time for potential new residents. As assbackward as it may be to both of us, the way the system works is an ever increasing amount of people will demand and eventually get due to sheer numbers transit improvements. You get an ever increasing amount of people by increasing the housing supply. If we don't any pittance of dollars we may be getting from the feds will instead be going to build yet another highway in places like Houston. The city needs to grow, first and foremost to act as a catalyst for all the improvement both you and I would like to see. I'd also point out more residents = increased tax revenue = more state/city funds for transit.

JeffDowntown

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 28, 2007

- Messages

- 4,795

- Reaction score

- 3,660

I get that Charlestown has transit issues, but paying for major solutions before the problem manifests is much harder than paying for minor solutions.

The successful examples of pre-planned new transit access are infill stations (Assembly and Boston Landing). These are basically no brainer infrastructure -- chump change in the grand scheme of transit infrastructure.

The kind of solutions that have not been built are the ones that take real capital commitment. It is simply much much harder to get the political will to spend billions rather than just millions.

The successful examples of pre-planned new transit access are infill stations (Assembly and Boston Landing). These are basically no brainer infrastructure -- chump change in the grand scheme of transit infrastructure.

The kind of solutions that have not been built are the ones that take real capital commitment. It is simply much much harder to get the political will to spend billions rather than just millions.

Transit is an issue but a more basic issue is the power grid. 5-6 power lines caught fire last night and fell to the street in areas with overhead wires in Charlestown. They all coincided with areas with new development i.e. House tear downs replaced with 2-5 units. Everyone running ac puts a strain on existing infrastructure, happened last summer in the same spots. Can the additional units over there have basic services without running into issues? Like fires...electrocution etc.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.