The Big Tangle

In the aftermath of the fatal I-90 ceiling collapse, a complicated legal fight has drawn in a phalanx of attorneys to defend pocketbooks and reputations. Such maneuvering has drawn comparisons to famed disputes in Boston history.

By Sean P. Murphy and Scott Allen, Globe Staff | April 8, 2007

The tunnel ceiling collapse that killed a Jamaica Plain woman last summer has triggered one of the most complicated legal fights in Boston history, court observers say, already drawing more than 100 attorneys, 17 companies, and dozens of engineers and workers into the burgeoning lawsuits and criminal investigations spawned by the tragedy.

The stakes are high: The lawsuit brought by the family of Milena Del Valle could cost those found responsible for her death tens of millions of dollars, while the state is seeking at least another $35 million for repairs and other losses from the accident.

Meanwhile, a state special prosecutor began bringing witnesses last week before a new grand jury to determine whether anyone should face criminal charges in the design and construction of the Interstate 90 connector tunnel ceiling. And federal prosecutors are considering fraud charges against several companies, including the overall managers of Big Dig tunnel construction at Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff.

With so much legal crossfire, the companies and their employees are standing behind a phalanx of lawyers to defend their pocketbooks, their reputations, and, potentially, their freedom. Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff, a joint venture of two enormous engineering companies, has hired David Kendall , the lawyer who defended President Clinton during his impeachment trial, to lead the defense against criminal charges.

"This case is about as complex as you will see in civil litigation," said William J. Dailey Jr. , Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff's lead lawyer in the Del Valle family civil lawsuit. In Dailey's 40-year legal career, he said, "I've never seen anything like it."

The price of so much courtroom wrangling, legal analysts say, could be long delays in getting a financial settlement for the three children and widower of Del Valle, people of modest means originally from Costa Rica.

M. Frederick Pritzker , chairman of the litigation department at Brown Rudnick Berlack Israels LLP in Boston, said he would not be surprised if the Del Valle family's lawsuit were bogged down by all the civil and criminal cases.

"Ultimately, it will sort itself out, but it could take years longer to resolve and cost much more" than if there were no criminal charges, Pritzker said.

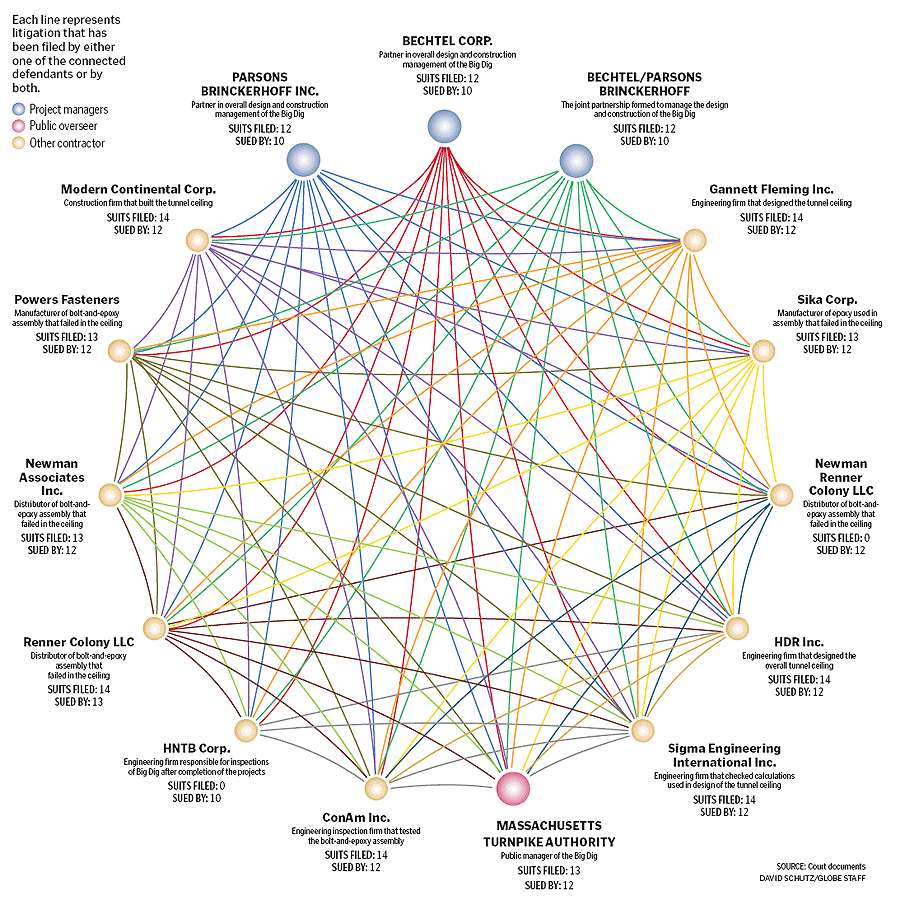

The family's suit has turned into a legal traffic jam, as each defendant has sued others to shift financial responsibility. So far, Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff and the other companies have filed a staggering 172 cross-claims against one another, each giving one defendant the right to seek money from another if they are blamed for Del Valle's death.

In addition, state special prosecutor Paul F. Ware Jr. has asked the judge in the Del Valle suit to freeze most activity for six months so that he can decide whether to seek criminal indictments without worrying that key witnesses could be called to testify publicly in a separate lawsuit.

Leo Boyle , lead attorney for the Del Valle family, has strongly opposed any delays. He told Superior Court Justice Stephen E. Neel in court last month that Ware "wants to come in here and say to the only innocent victim in all this that we want to stop you from finding the truth."

Ware insists that he is on the side of the Del Valle family. But he says criminal prosecutors have a job to do.

"What Mr. Boyle is really complaining about here is the criminal justice system," Ware told Neel. His boss, Attorney General Martha Coakley, has frozen the state lawsuit seeking financial compensation from 17 companies connected to the ceiling project.

Neel has not ruled on Ware's motion, but he has lamented from the bench on what he calls the "imperfect juncture" between civil lawsuits and criminal cases.

For the sheer amount of legal maneuvering, Pritzker said, the tunnel ceiling case invites comparisons to the famed 1970s dispute over a design flaw in the John Hancock Tower that caused windows to begin popping out, to the terror of the people below. John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Co. and the building's architect, general contractor, glassmaker, and structural engineer filed a total of six suits and countersuits against one another, creating a court file 6 feet thick before the suits were settled privately in 1981.

As with the windows dispute, it remains unclear exactly who is most to blame for the concrete tunnel ceiling that came crashing down just six years after it was built. Project documents show that designers cut corners on safety, workers made numerous mistakes in installation, and the state failed to inspect the job after it was completed. Dozens of companies, however, were in some way connected to the project, and the Del Valle family and the attorney general are not suing the same entities.

The National Transportation Safety Board could clarify some of those questions when it issues a final report on the causes of the accident, expected in July.

Dailey believes, however, that the federal and state criminal investigations make the ceiling case more complex than the Hancock windows or other famously tangled Boston cases such as the 1986 environmental lawsuit against W. R. Grace, which inspired the book "A Civil Action." Dailey said every defense lawyer in the Del Valle case has to simultaneously worry that anything a client says could be used by criminal investigators against him or her.

So far, at least 100 lawyers are involved in the various legal actions, including 45 who have made appearances in the Del Valle suit, at least 20 lawyers for the state and US Attorney Michael J. Sullivan, as well as criminal lawyers for the companies and their employees. The number probably will grow if criminal charges are brought: Special prosecutor Ware, brought into the case last month from the law firm Goodwin Procter LLP, has said he may recruit lawyers from his firm to assist if indictments are issued.

Yet Dailey, the lawyer for Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff, said he is optimistic the Del Valle suit, at least, can be resolved relatively promptly once state and federal prosecutors clarify which criminal charges, if any, they will seek. Ware has said he and Coakley expect to decide by June whether to seek indictments. The US attorney's office has been less clear on its deadline for seeking fraud charges, though Ware said in court recently that their investigation "may go on for some number of months."

"I think this is going to be surprisingly quick in being resolved," said Dailey.

But Boyle, the lawyer for the Del Valle family, is less sure, fearing that Ware will ask again to delay the family's lawsuit if he obtains criminal indictments.

Legal analysts say that proving the ceiling accident was a result of criminal negligence will be difficult, because prosecutors must show that people knew the ceiling was dangerous when they opened the tunnel to the public. As a result, Boyle said, prosecutors could hold up his work, but fail to convict anyone. "My level of confidence that they're going to get to the bottom of what happened is very low," he said.

Sean P. Murphy can be reached at

smurphy@globe.com.

? Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.