Alvaro critiques MBTA panel

Former MassDOT board member says it's unfair to blame board, senior officials

GABRIELLE GURLEY

Apr 21, 2015

FERDINAND ALVARO UNDERSTANDS the MBTA’s finances and inner workings better than most outsiders. Ask him who is to blame for the bundle of issues that led to the transit agency’s breakdown this winter and he has a simple answer: “Everybody.”

Gov. Deval Patrick appointed Alvaro, an attorney with expertise in finance and administration, to the former MBTA board of directors in 2008, where he helped oversee the transit agency’s budget. After the 2009 transportation reforms merged the MBTA board into a single MassDOT board, Patrick reappointed Alvaro and two others, a decision which set off a firestorm of criticism.

When the MassDOT board expanded to seven members in 2012, Patrick kept the Republican on. Alvaro frequently criticized the agency for its handling of MBTA commuter rail contracts and was the only board member to vote against the 2012 fare increase. He stepped down from the MassDOT board of directors when his term expired in 2013.

Now a partner-in-charge at the law firm Gonzalez Saggio & Harlan, Alvaro applauds Gov. Charlie Baker’s decision to take a fresh look at the MBTA. But he disagrees with the special review panel’s focus on management over financial issues and Baker’s decision to ask for the resignations of six of the seven members of the MassDOT board of directors. Alvaro also says that he wasn’t aware the T was using capital funds to pay salaries.

The six MassDOT board members stepped down Tuesday. (Transportation Secretary Stephanie Pollack is the sole remaining board member.) With the exception of a defiant John Jenkins, the former MassDOT board chairman, members of the board of directors declined to comment at the group’s last board meeting earlier this month. CommonWealth turned to Alvaro to get his reading on the MBTA special panel, how a possible control board might work, the lack of oversight of the T by state lawmakers, and how business could step up.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Who is responsible for the fix the MBTA is in?

Although the MBTA special review panel didn’t quite say it, I disagree with the implication that senior management and the MassDOT board are responsible for the transit agency’s problems. The panel report was very informative and useful and a good guide for fixing a lot of things in the future. But it’s unfair to blame the people at the helm for problems that have occurred over decades.

I was talking to somebody about this and they said, OK, so we shouldn’t blame anybody. My response was, no, you should blame everybody. Everybody who has had anything to do with that system or sat in the Legislature for the last 50 years bears some degree of responsibility for the decline, including me.

The backlog in maintenance is something that has been an issue since I joined the old MBTA board back in 2008. The problems that the panel pointed out like lax labor performance are more a function of the things that have been forced on the T by the Legislature, like the Pacheco Law and binding arbitration in their union contracts. What has been inferred—that the entire management is dysfunctional— is completely unjustified.

Why?

A lot of the people who are there are top-notch managers. I would hire [Interim General Manager] Frank DePaola to run any engineering group or the T. [Chief Financial Officer] Jonathan Davis has done the best with a bad situation.

The panel seemed to not give enough weight to the fact that the underlying cause of all of this is money. The report said that one of the reasons that the debt hasn’t been paid down is because it has been refinanced. I don’t necessarily view the refinancing as a bad thing.

The reason that debt has been refinanced is that Jonathan has done a great job of taking higher interest debt and refinancing it into lower interest debt to reduce the interest burden on the organization. Anyone who infers that the financial mess at the T is because of the CFO is just flat out wrong.

The transportation financing mechanism is deeply flawed in this state. In any business scenario, if you write a business plan and your assumptions turn out not to be true, you rewrite the business plan. The Legislature created forward funding based on a number of assumptions. Those assumptions proved to be vastly inaccurate. Forward funding wasn’t going to create the kinds of revenues that the Legislature had anticipated when it was created. They never did anything to fix the funding formula. That was one of things that drove the MBTA to take on enormous amounts of debt.

You do not agree with disbanding the current board?

As a businessman, it is always a mistake to do wholesale removals of anybody from an organization. If I were on the panel, my advice would have been that the governor should assess every board member on his or her merits and make a decision to ask that person to resign based on that assessment. You lose some institutional knowledge that will be hard to regain when you have a brand new secretary of transportation, a brand new MBTA general manager, and an entirely new board of directors.

There hasn’t been strong public opposition to a fiscal and management control board. Isn’t it a way for Baker to take responsibility and get the Legislature off the hook?

In all of this drama, the people who have been the least taken to task are state lawmakers. The people who are ultimately accountable for transportation or any public good in a democracy are public officials.

When I voted against the last fare increase, the reason I gave was that the Legislature had been completely uninterested apparently in the fate of our customers. They had not shown up with any support. There was no choice but to increase fares. I knew that my one dissenting vote would be symbolic, but I felt like I had to call them out.

Baker has stepped up. A governor can propose any innovation or reform that he or she wants. But if the Legislature doesn’t fund it, it isn’t going to happen.

I didn’t fully agree with Deval Patrick’s last transportation plan, but I agreed with a lot of it. The Legislature, while saying that they were committed to fixing transportation, stripped out an enormous amount of funding from that proposal. Again, nobody took them to task for it. I wouldn’t say that Patrick’s plan would have prevented what occurred this winter. But if the funding that he asked for had been provided, we would be on our way to fixing the problem.

Should the Legislature have been more assertive in its oversight of the MBTA?

Absolutely.

What was your experience with state lawmakers?

I don’t think that the transportation oversight committee really provides meaningful transportation oversight. The Legislature gets involved with the oversight of transportation when it is front-page news. When it isn’t, state lawmakers really leave it to the governor to deal with things.

In 2009, there was an expectation that the board would be more assertive on these issues. Some argue that the board did not step into that role. Did the board operate as a rubber stamp?

You can Google my name and see things that I said at those board meetings that would not support that there was rubber stamping going on. I and others observed regularly that the MBTA couldn’t afford to do all of the expansion that it was doing.

Ordinary expenses like salaries should not be capitalized; we actually fixed this at the MassDOT. There were many instances when management presented real estate deals or other contractual arrangements where we told them to go out and get better terms for the agency. These are things the board told them to do during executive [closed to the public] sessions.

The MBTA paid employees out of the capital budget like the state highway division did. Were you aware of that?

On a number of occasions, I indicated that it was a profoundly bad idea to capitalize operating expenses, although it wasn’t illegal or improper under accounting rules. I had not been aware that they had been doing it at the MBTA. I never commented on it because I wasn’t aware that it was going on at the MBTA. I don’t recall having discussed that practice in the context of the MBTA with anybody while I was on the board.

What do you make of employee problems like high absenteeism?

At the April MassDOT board of directors meeting, [former board member] Dominic Blue of Springfield said that it seems like that we are heading toward a time when the whole place would be unionized. Secretary Pollack said we are pretty much already there: Of more than 6,400 employees at the MBTA, roughly about 200 are not unionized.

I am not anti-union. But if you have a garage that is 100 percent unionized and you have multiple unions to deal with, it would be a real challenge for management – and perhaps an insurmountable challenge — to make sure that everybody toes the line, unless you want to be tied up with nonstop union grievances, which would be even more disruptive. If you have a crackdown, you can be sure that there will be grievances filed by the barrel.

I wouldn’t let management off the hook 100 percent, but it is a more complex issue. Management is a) constrained in what they can contract out; b) stuck with a lot of contracts that they would not have agreed to if an arbitrator hadn’t forced them to; and c) dealing with a Legislature that understands that all those unions turn out votes.

Senior managers and rank-and-file employees are in the headlines, but there hasn’t been much discussion about mid-level managers. How should they be handled?

If there is a fiscal and management control board, one of things you might want to do is to have a thorough evaluation of critical middle managers. More than in many other agencies, the T was a place where political favors were done. I support you, my cousin needs a job; fine, he’s the new so-and-so of the MBTA.

That continued for a number of years and, to some extent happens today, though not in as drastic a way as it used to occur. When you have an organization where some of the hiring decisions are made based on politics rather than capability and where many of the people who were hired on that basis are still in the organization, you get a fair number, not to say all, but some unqualified people. A lot of people are coming up on retirement. Typically what happens is that the good people will leave because they will have other employment opportunities, and the not-so-good people will stay.

Should every governor get to appoint a board of directors?

The terms should be set so at least a majority of the board is replaced when the administration changes. You don’t need to change the law. To do that, you just need to set people’s terms so it works that way. What that majority is depends on the party of the governor who is appointing. If it’s a Democrat, four Democrats; if it’s a Republican, four Republicans. It was slightly disingenuous of our previous governor to reappoint so many people whose terms were going to continue years into the new governor’s administration.

What qualifications should board members have?

You don’t need seven transportation experts on the board; that’s not necessarily a good thing. You need a solid financial person and a solid engineer. To me, [MIT civil engineering professor] Andrew Whittle was one of the most valuable members of the board. In an organization where more than 90 percent of the employees are unionized, it is sensible to have somebody on the board who can share the union’s perspective.

Should a board member be compensated?

MassDOT board positions should not be paid. However, as I read the tasks of the proposed fiscal and management control board, they don’t seem to be things that can be done at once-a-month meetings over a three-year period.

If I wanted to effect drastic change, I would create something akin to the Massachusetts Gaming Commission, which is a dedicated, full-time compensated group of people with the necessary skill sets to do what needs to be done.

Should riders take on more of the MBTA’s financial burden by paying higher fares?

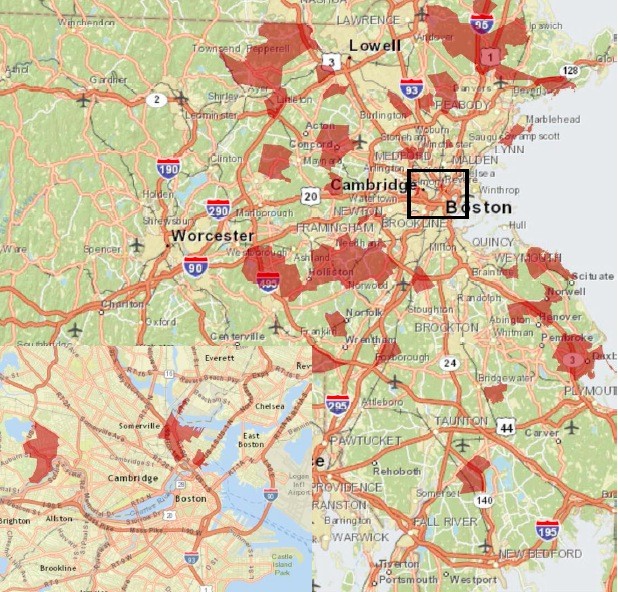

Secretary of Transportation Pollack is looking at a restructuring of the fares so that people with less means will pay less. I applaud the idea of doing it on a needs-based basis. My neighbors who commute in from Marblehead and take the train from Swampscott can very easily afford an increase in their commuter rail fees.

State lawmakers point to the success of the gas tax indexing repeal as evidence that voters don’t want to pay more taxes for public transportation improvements.

It is a paradox in the transportation space. Folks that represent the disabled say, don’t you dare stop making accessibility improvements, which is an enormous part of the budget. Elderly folks say, I know you’ve got a big problem but don’t you dare cut back The Ride.

One of the groups that has benefited the most from public transportation, and they essentially get it for free, is the business community. One of the things, I proposed on my time on the board that never got anywhere was a reinvention of the basic transportation funding formula that would take into account the transit benefits that businesses get.

Now I am a good Republican. I do not lightly say that business taxes should be increased. But as somebody who knows a little bit about transportation and the value that it provides to our economy, it would be appropriate to do two things. They would both have a salutary effect on the system. Assess businesses some portion of the cost of transportation, and, in exchange for that, give business a place at the table in the management of the transportation system. The price of admission would be you pay some portion, in some way, of the cost of the transportation system.

Do you think the MBTA is up to the challenge of preparing for the 2024 Olympics?

That is an interesting question. If the Legislature makes a real commitment to make the kind of investment that’s required to bring the infrastructure up to snuff, then the answer is yes. If the Legislature does not make that commitment, then the answer is no.

The T can’t do anything unless it has the money. So the bar is higher now than it was before this past winter. Before this past winter the question was, can we execute all the expansion projects that would be necessary to accommodate the Olympics? The question now is, can we fix the core system and accomplish all the expansion that would be necessary to accommodate the Olympics?

If you really want to accelerate that process, and we should want to accelerate that process, put people on the control board who are going to work on the problem on a full-time basis and get paid for it. If you do that, the time horizons shrink.