Fate Of Dainty Dot in Landmark's Hands

Aug 3, 2007

by Adam Smith

Another historic building in Chinatown is likely to face the wrecking ball to make way for high-rise housing.

The future of the 118-year-old Dainty Dot building at 120 Kingston St. is now in the hands of the Boston Landmarks Commission, which will decide as early as August 14 whether the low-rise brownstone is worthy of landmark protection.

The commission's staff, which does not vote on landmark designations, determined that the Dainty Dot does not meet criteria for landmark status, partly because about half the building was demolished in the 1950s for construction of the Central Artery highway.

Without landmark protections, the building is vulnerable to demolition.

The Massachusetts Historical Commission says it "does not concur" with the Landmarks' position and feels the building is worthy of designation on the National Register of Historic Places. The MHC, however, cannot override the city body.

During a packed Landmarks Commission hearing on July 24, Leather District residents and representatives of Chinatown community groups spoke in favor of and against saving the six-story brownstone that has links to the textile industry and is one of the oldest remaining wholesale buildings in Boston's business district.

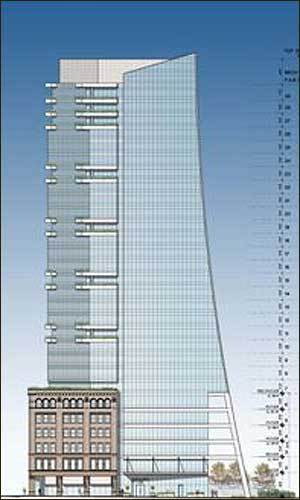

A private developer, the Hudson Group, plans to raze much of the Dainty Dot, save for a corner of its facade that will wrap around a small segment of the Hudson Group's planned 29-story tower at 120 Kingston St.

The Hudson Group, which said it agrees with the Landmark Commission's assessment of the Dainty Dot, plans to build 180-units of high-end housing.

The developer also promises to create a separate affordable-housing project nearby in Chinatown that will provide between 27 and 50 units of housing for low- and moderate-income earners. All developers of sizeable housing projects in Boston are required by the city to provide affordable housing or money for such housing that is equal to 15% of the development; 27 units is 15% of the proposed 180 market-rate housing units.

The project and its potential demolition of much of the Dainty Dot is in some ways reminiscent of the planned high-rise Kensington Place project, whose developers completely demolished the 1908 Gaiety Theatre on Washington Street a few years ago. In the case of the Gaiety, which was designed by Wang Theatre architect Clarence Blackall, the Boston Landmarks Commission staff also recommended no protections and stated it did not meet landmark criteria. (The Kensington housing tower has not yet begun construction though it won all necessary approvals and cleared its development site a few years ago.)

While the Landmarks hearing in 2003 for the Gaiety lasted several hours and was full of lively debate, the meeting last week for the Dainty Dot was low-key in comparison.

The most passionate testimony at the hearing came from Bill Moy, who is not a Chinatown resident but has been involved with the community for nearly 30 years. He opposed protecting the Dainty Dot, just as he had the Gaiety four years earlier.

"Historically, it's not worth saving," said Moy of the Dainty Dot. "

'd like to go to the future of Chinatown."

He added that the Hudson Group's plan to save the facade is a "compromise."

Chinatown representatives who are involved in developing the affordable housing project by partnering with the Hudson Group also spoke against saving the Dainty Dot.

"I am very sensitive to the losses of Chinatown and the Leather District. My father's house was demolished on Mass Pike for the on ramp," said Allen Chin, vice chairman of the Chinese Economic Development Council, which would build the affordable housing project for the Hudson Group. But, he said, at the Dainty Dot, "there's just not much left to preserve."

The Chinese Progressive Association, however, which opposes the Hudson Group's high-rise, said the Dainty Dot should be saved because it represents an important part of Boston's history.

Stephanie Fan, a former resident of the area and a current member of the Chinese Historical Society, also supports keeping the Dainty Dot. Though she wasn?t present at the meeting, her letter of support was read aloud.

She wrote that buildings like the Dainty Dot provided a ?beautiful? backdrop while growing up in the commercial area of Chinatown.

"Now, with inner cities at the forefront of development driven by the desire of corporate wealth, more of these buildings are in danger of being replaced by sleek modern towers," wrote Fan.

Many Leather District neighbors of 120 Kingston Street said they felt it should be saved, in part because it represents the construction of the Central Artery.

"The Central Artery especially changed the face of the city," said Sarah Kelly of the Boston Preservation Alliance, which supports saving and restoring the Dainty Dot.

"A building that is still nice looking, despite having such a mutilated history, should remain,? testified Eugenie Beal, founder of the Boston Natural Areas Fund, at the hearing.

But Gilbert Ho, treasurer of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the group that is selling property to the Hudson Group for the affordable project, disagrees.

"I never see a Duck Tour stop by that building," he said as he left City Hall after the meeting ended.

Link