Long Drop

Credit crisis turns market for commercial property from hot to suddenly cold in Boston, across country

By Thomas C. Palmer Jr.

Globe Staff / December 7, 2007

The unprecedented frenzy in the commercial real estate sales market seemed as if it would never end.

For five years, office buildings were turning over with increasing frequency, at ever-increasing prices. Three-quarters of downtown Boston's top-quality office properties changed hands at least once in the last five years. With sales of $7.3 billion by the middle of the summer, the market was on track to set another record in 2007.

But in August, the meltdown in subprime mortgages triggered a wider credit crisis on Wall Street. Overnight, potential buyers could no longer borrow money to do deals, bringing the commercial property market in Boston and across the country to a standstill.

"It's not completely dead, but it's been knocked on its bottom," said Rob Griffin, president of Cushman & Wakefield of Massachusetts Inc., a commercial brokerage. "It's certainly been chaos since August."

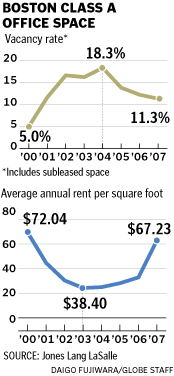

The sales slowdown should not have an effect on the broader economy, industry analysts said. Demand for office space remains high in Boston, and leasing rates have never been stronger. But the enormous profits that commercial real estate owners and investors have enjoyed for several years are over for the foreseeable future.

Now, many properties sit on the market or have been withdrawn. Some deals fell through and others sold for below asking price. Sales in the third quarter this year plummeted to under $1 billion, from the $2.5 billion of the third quarter of 2006.

Even trophy properties such as the Hancock Tower, which twice sold quickly in the past four years, were hit by the slowdown. The Hancock's owner, Broadway Partners Fund Manager LLC, received an unsolicited offer in the spring for the tower and other properties. But in late July, when credit markets were becoming volatile, the prospective buyer backed out.

"The market blew up," said Scott Lawlor, Broadway Partners' chief executive.

Several other owners of Boston properties have also been unable to sell buildings they were marketing - even though industry specialists predicted they would draw record numbers of bidders and the highest prices yet.

Normandy Real Estate Partners could not sell a portfolio of about eight buildings it put on the market earlier this year, and Brickman, a New York private equity company, this fall removed a slate of about 10 buildings that didn't sell. Brickman's holdings include One Bowdoin Square.

Fortis Property Group, co-owners of One Lincoln Street, one of Boston's newest buildings, recently attempted to sell it, but apparently the offers weren't good enough.

"My impression is they were hoping for a big huge number, and the pricing was not as dramatic as they'd hoped," Lisa M. Campoli, executive vice president of Meredith & Grew, said after speaking to a gathering of real estate executives yesterday.

Eastdil Secured LLC, the real estate investment advisers hired by Broadway, Brickman, and Normandy, declined to discuss the sales efforts. Fortis could not be reached for comment.

Peter F. Korpacz, executive managing director of Weiser Realty Advisors LLC, said, "A number of deals actually blew up."

Typically on a national basis, 2 percent of commercial property sales fall through for various reasons, such as financing fails to come through, he said; this fall the number was 6.5 percent.

Some deals that did close experienced something that hasn't routinely happened for about five years -"repricing." Buyers were able to negotiate prices downward 5 to 8 percent, Korpacz said.

Even with the dramatic slowdown, 2007 could be a record year in Boston, according to Real Capital Analytics, a New York firm that tracks transactions. That's because the year started off with a monumental transaction: the $39 billion purchase of the holdings of Equity Office Properties Trust by private equity firm The Blackstone Group LP. Part of the sale included the biggest portfolio of Boston office buildings held by one owner.

The turn in the market was swift. As recently as late June, Douglas M. Poutasse, executive director of the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, said: "It doesn't get any better than it's been."

The trouble first emerged from the residential real estate market. Wall Street investors were big buyers of investment portfolios consisting of subprime and other lower-quality home mortgages. When homeowners began defaulting on their loans this year, those investors were left holding investments worth substantially less. Facing losses, the investment community abruptly stopping pumping new funds into the lending market.

The credit shortage spread to the larger commercial loan market, and suddenly a source of capital from Wall Street that had fueled the buying frenzy in office buildings had also evaporated.

"It's just stopped," said Michael Fascitelli, president of Vornado Realty Trust, which is increasingly investing in Boston properties.

Executives say the residential mortgage market wasn't the only factor in the decline of commercial real estate investing. Riskier loans were showing up in commercial investment pools being sold on Wall Street as well.

Predictions vary on whether the go-go days will return soon, or at all. "I personally think this is a very dangerous time to do transactions," Scott M. Sperling, copresident of the private equity firm Thomas H. Lee Partners LP, told a group of executives last month.

Many other industry executives predicted the office market would improve next year, although a few warned the credit crisis could make things worse in the coming weeks before the real estate investment market improves. They said Wall Street firms have to work out at least $40 billion in troubled residential loans before they resume investing in commercial properties.

Nevertheless, Janet N. Krolman, director of the investment advisers Holliday Fenoglio Fowler LP, noted that unlike the residential market, there have been few casualties so far. "There's almost no delinquency," she said. "The commercial market is very sound."

Thomas C. Palmer Jr. can be reached at

tpalmer@globe.com.

? Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.