Joe_Schmoe

Active Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 374

- Reaction score

- 0

Boston architecture has reached an impasse. The brutal physical and psychological wounds modernism inflicted on Boston in the 50s and 60s have never healed, and while many modern architects arrogantly refuse to acknowledge the damage done, traditionalists stubbornly prevent architecture from advancing. A kind of truce was called in recent decades with contextualism. However, contextualism has seemed to run out of steam of late and half-hearted and uninspiring buildings have become the norm. Here are some thoughts I have had on ways to push Boston architecture forward and cut the Gordian knot between history and innovation that paralyzes so much of Boston?s recent buildings.

Palette:

Boston is blessed to have what few American cities have: a palette. Most American cities are indistinguishable from one another, but San Francisco has its whites, Santa Fe has its adobe, New York (at least formerly) had its limestone, and Boston has its reds and browns. Tragically, far too much recent development dilutes Boston?s palette and substitutes colors that would be equally at home in any of the world?s cities. This is not to say that every building has to confirm to this color scheme, after all, Beacon Hill is not all red brick, but the violations serve to enhance the tone rather that detract from it. The same can not be said for much new construction.

(How unified palette contributes to effective skyline)

(Notice that each building is slightly different in color, yet holds together as a unity.)

It is crucial to realize Boston?s palette did not develop accidentally as many seem to suppose. Architects act as though Boston?s obsession with brick is mere sentimentality, or worse simply a stubborn refusal to be open-minded. On the contrary, brick continues to reproduce in Boston because it adapts to its environment successfully. Just as white works wonderfully in sunnier climes, Boston is a grim and bleak place much of the year, and white quickly becomes grey after a few years and there is all to much grey as it is in February and March. The South Boston waterfront with its cream and grey buildings is going to be almost uninhabitably grim in the winter months, just as is the Christian Science center is with its vast expanse of windswept concrete.

(Why lighter colors don?t work in Boston)

Materials:

Brick, on the other hand, works beautifully in New England with its seasons. Nothing is greyer than Boston in, say February or March, but the red buildings of the North End, South End, or Beacon Hill provide much needed color and warmth.

However, brick works best as a background on which other architectural elements are applied, and when brick is brought into the foreground it can become horribly repetitive and dull. Thus, red brick does not lend itself to modernism as modernism loves to emphasize the material rather than its adornment whereas pre-modern architecture put the underlying material in the background. Modernism's favorite virtues are the "dramatic" and "presence." Too many modern architects in Boston have thought that the way to achieve drama is to make things vast, as in vast expanses of glass or concrete. If vastness is what causes a building to have dramatic presence, it is thought, vast expanses of brick can be dramatic as well. However, there is nothing dramatic about a vast expanse of brick, as our beloved City Hall plaza or Transportation building shows.

(Too much of a good thing)

However, it is possible to respect the Boston palette while not resorting to red brick. The Allston library by Machado and Silvetti is a great example for a building that is not brick, uses original materials, is indisputably modern, but successfully keeps what works in the Boston palette.

(I would love to see Machado and Silvetti do an entire condo complex with these tiles)

(5 different types of material that hangs together beautifully)

Nike Town is another example where a red slate is used instead of brick.

Neo-humanism:

Modernist architects early on realized that the 20th century was the century of the masses: mass transportation, mass media, mass education, mass production. The architecture they practiced was an attempt to reflect this political change but ended up being cold, alienating, and impersonal. The 21st century is going to be a flight from modern alienation and anonymity and a search for a greater sense of intimacy and community. Boston can be in the forefront of this movement. It is difficult to see how this will be expressed in architecture, but a reaction against the homogenizing universality of International style, towards diversity and regionalism is guaranteed. I can foresee an attempt to break up larger buildings into smaller, human-scaled, segments, and to humanize the cold impersonal glass curtain wall similar to how musicians attempt to make digital music sound ?warmer? by adding the warm hiss that older records naturally had.

Ornamentation:

Modern architecture?s banishment of ornamentation has long since ceased having any sort of aesthetic or intellectual underpinning and has become mere dogma. Here is the sculpture of saints from H.H. Richardson?s Trinity Church.

There is no reason that architects could not again work with sculptors in this way and a modern building incorporate modern sculpture. Here is a half-hearted attempt in that direction?the sea-serpent sculpture on the South Boston waterfront:

Likewise, it is pure arrogance to think that the unadorned style of modern architectural elements, columns for example, will be the final word for the rest of time and that a new style will never come along. It is time to innovate and come up with a new style.

It is pure arrogance to believe that architecture will eternally cling to the unadorned modern columns and no new style will take its place. Eventually there will be a new style of these architectural elements and Boston should be the place it is born.

Texture:

Architecture has been sleek and smooth for going on 90 years now. It is long overdue for a reaction. A truly cutting-edge and original style will rediscover the virtues of texture in materials. Again, Machado and Silvetti?s Allston public library provides a nicely textured and original fa?ade.

Form:

The last nail in the coffin of modernism has been the recent abandonment of the ?form follows function? mantra that was modernism?s raison d?etre. Having abandoned traditional building materials and restricting themselves to the modern, having foresworn texture for the sleek, having outlawed ornamentation, all modern architecture has left to play with is form. This results in the twisting, pulling, stretching, and bending that make up the entirety of architectural originality today. Liebeskind and Gehry, among others, have taken this to ridiculous lengths, and a conservative reaction is guaranteed.

In my opinion, the weakest part of Machado and Silvetti?s Allston public library is the pass? inverted roofline. In a city full of far too many dull boxes, some variety of form is welcome, but Boston should resist the urge to hop on the current bandwagon of ridiculous, and in their own way, ostentatious, modern buildings.

Composition:

It has been often repeated that what makes Boston the great city that it is are its many neighborhoods. A new Boston style of architecture would abandon the notion that the unit of architectural aesthetic evaluation is the individual building and come to realize that the neighborhood is equally the unit of evaluation and that when constructing a building, the architect is contributing to a larger artistic composition: the neighborhood. The building is as much a part of a preexisting whole as it is a whole itself. Thus the architect needs to consider whether this building contributes to or detracts from this larger composition as much as they consider the quality of their individual building. Is the building being a good neighbor, or a loud, arrogant, and disruptive egotist? For example, Hugh Stubbins? buildings for Boston Hospital completely ignored and overwhelmed the existing fabric set down by Gridley Fox Bryant.

(Bad neighbor)

(Why did this building move to Boston? It could have been equally at home in any city.)

Audience:

The first thing a writer learns to ask is ?who is your audience.? Writing for a group of specialists, or laymen, children, or students will of course affect the tone and style of ones writing. Architects need to ask the same question, who is the audience of this building? All too often it is obvious that the audience of much of today?s architecture is other architects. The building is meant to impress other avant garde architects, to make one?s reputation among ones peers, to get noticed by journals or academics. A new Boston style?a democratic rather than aristocratic style?would have as its audience the people of the neighborhood or city where the building is being made. This does not mean that the building needs to pander to the tastes of the crowd, to reproduce what the layman is used to, or to simply reach for the lowest common denominator. But it does force a change in the architect?s attention, to realize who this building is for, to stop considering the people of the neighborhood as mere philistines whom the architect is going to educate from on high. For example, H.H. Richardson?s Romanesque buildings were quite a departure from the existing status quo, but always had the attitude that they were there to serve the people who were going to use them, he never sneered at the tastes of his audience the way much so-called cutting edge architecture seems to.

Landscaping:

Landscape architecture has progressed little in the US since Olmstead. The goal still seems to be the recreation in reality of 18th and 19th century landscape painting. There have been some adjustments informed by the greater understanding of ecology?the banishment of invasive species for example. This movement must be pushed forward. A Boston style of landscaping should have as its point not the creation of a pastoral idyll, but the promotion of maximum biodiversity. For example, I remember reading of a courtyard that was being built in honor of a resident who was an avid birder. The plantings were chosen by what would be most attractive to different species of birds at different times of the year. This promotion of biodiversity should be norm and not the exception and the standard of beauty should be nature?s abundance, the pleasure derived from the perception thereof, and not the amusement park experience of wondering through a living idealized landscape painting.

Affect

Finally, a new Boston style, "Boston Neo-humanism," would re-examine what emotional affect the architect should have on the viewer. Whereas modernism always seeks to challenge the viewer, to confound expectations, or to cause awe, or anxiety, or at best to "intellectually challenge" the viewer through irony, confrontation, or even spite, there is a call for a new approach. I vote that the architect should always strive to produce buildings that the viewer would love.

Palette:

Boston is blessed to have what few American cities have: a palette. Most American cities are indistinguishable from one another, but San Francisco has its whites, Santa Fe has its adobe, New York (at least formerly) had its limestone, and Boston has its reds and browns. Tragically, far too much recent development dilutes Boston?s palette and substitutes colors that would be equally at home in any of the world?s cities. This is not to say that every building has to confirm to this color scheme, after all, Beacon Hill is not all red brick, but the violations serve to enhance the tone rather that detract from it. The same can not be said for much new construction.

(How unified palette contributes to effective skyline)

(Notice that each building is slightly different in color, yet holds together as a unity.)

It is crucial to realize Boston?s palette did not develop accidentally as many seem to suppose. Architects act as though Boston?s obsession with brick is mere sentimentality, or worse simply a stubborn refusal to be open-minded. On the contrary, brick continues to reproduce in Boston because it adapts to its environment successfully. Just as white works wonderfully in sunnier climes, Boston is a grim and bleak place much of the year, and white quickly becomes grey after a few years and there is all to much grey as it is in February and March. The South Boston waterfront with its cream and grey buildings is going to be almost uninhabitably grim in the winter months, just as is the Christian Science center is with its vast expanse of windswept concrete.

(Why lighter colors don?t work in Boston)

Materials:

Brick, on the other hand, works beautifully in New England with its seasons. Nothing is greyer than Boston in, say February or March, but the red buildings of the North End, South End, or Beacon Hill provide much needed color and warmth.

However, brick works best as a background on which other architectural elements are applied, and when brick is brought into the foreground it can become horribly repetitive and dull. Thus, red brick does not lend itself to modernism as modernism loves to emphasize the material rather than its adornment whereas pre-modern architecture put the underlying material in the background. Modernism's favorite virtues are the "dramatic" and "presence." Too many modern architects in Boston have thought that the way to achieve drama is to make things vast, as in vast expanses of glass or concrete. If vastness is what causes a building to have dramatic presence, it is thought, vast expanses of brick can be dramatic as well. However, there is nothing dramatic about a vast expanse of brick, as our beloved City Hall plaza or Transportation building shows.

(Too much of a good thing)

However, it is possible to respect the Boston palette while not resorting to red brick. The Allston library by Machado and Silvetti is a great example for a building that is not brick, uses original materials, is indisputably modern, but successfully keeps what works in the Boston palette.

(I would love to see Machado and Silvetti do an entire condo complex with these tiles)

(5 different types of material that hangs together beautifully)

Nike Town is another example where a red slate is used instead of brick.

Neo-humanism:

Modernist architects early on realized that the 20th century was the century of the masses: mass transportation, mass media, mass education, mass production. The architecture they practiced was an attempt to reflect this political change but ended up being cold, alienating, and impersonal. The 21st century is going to be a flight from modern alienation and anonymity and a search for a greater sense of intimacy and community. Boston can be in the forefront of this movement. It is difficult to see how this will be expressed in architecture, but a reaction against the homogenizing universality of International style, towards diversity and regionalism is guaranteed. I can foresee an attempt to break up larger buildings into smaller, human-scaled, segments, and to humanize the cold impersonal glass curtain wall similar to how musicians attempt to make digital music sound ?warmer? by adding the warm hiss that older records naturally had.

Ornamentation:

Modern architecture?s banishment of ornamentation has long since ceased having any sort of aesthetic or intellectual underpinning and has become mere dogma. Here is the sculpture of saints from H.H. Richardson?s Trinity Church.

There is no reason that architects could not again work with sculptors in this way and a modern building incorporate modern sculpture. Here is a half-hearted attempt in that direction?the sea-serpent sculpture on the South Boston waterfront:

Likewise, it is pure arrogance to think that the unadorned style of modern architectural elements, columns for example, will be the final word for the rest of time and that a new style will never come along. It is time to innovate and come up with a new style.

It is pure arrogance to believe that architecture will eternally cling to the unadorned modern columns and no new style will take its place. Eventually there will be a new style of these architectural elements and Boston should be the place it is born.

Texture:

Architecture has been sleek and smooth for going on 90 years now. It is long overdue for a reaction. A truly cutting-edge and original style will rediscover the virtues of texture in materials. Again, Machado and Silvetti?s Allston public library provides a nicely textured and original fa?ade.

Form:

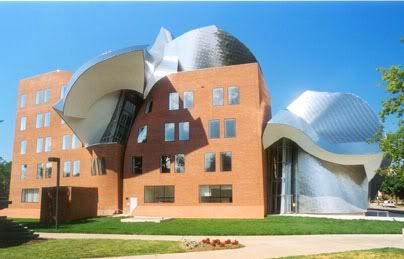

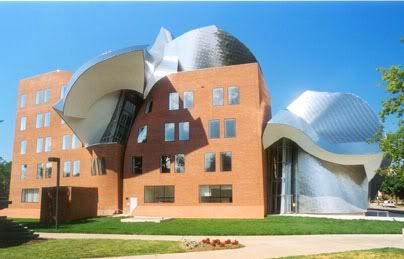

The last nail in the coffin of modernism has been the recent abandonment of the ?form follows function? mantra that was modernism?s raison d?etre. Having abandoned traditional building materials and restricting themselves to the modern, having foresworn texture for the sleek, having outlawed ornamentation, all modern architecture has left to play with is form. This results in the twisting, pulling, stretching, and bending that make up the entirety of architectural originality today. Liebeskind and Gehry, among others, have taken this to ridiculous lengths, and a conservative reaction is guaranteed.

In my opinion, the weakest part of Machado and Silvetti?s Allston public library is the pass? inverted roofline. In a city full of far too many dull boxes, some variety of form is welcome, but Boston should resist the urge to hop on the current bandwagon of ridiculous, and in their own way, ostentatious, modern buildings.

Composition:

It has been often repeated that what makes Boston the great city that it is are its many neighborhoods. A new Boston style of architecture would abandon the notion that the unit of architectural aesthetic evaluation is the individual building and come to realize that the neighborhood is equally the unit of evaluation and that when constructing a building, the architect is contributing to a larger artistic composition: the neighborhood. The building is as much a part of a preexisting whole as it is a whole itself. Thus the architect needs to consider whether this building contributes to or detracts from this larger composition as much as they consider the quality of their individual building. Is the building being a good neighbor, or a loud, arrogant, and disruptive egotist? For example, Hugh Stubbins? buildings for Boston Hospital completely ignored and overwhelmed the existing fabric set down by Gridley Fox Bryant.

(Bad neighbor)

(Why did this building move to Boston? It could have been equally at home in any city.)

Audience:

The first thing a writer learns to ask is ?who is your audience.? Writing for a group of specialists, or laymen, children, or students will of course affect the tone and style of ones writing. Architects need to ask the same question, who is the audience of this building? All too often it is obvious that the audience of much of today?s architecture is other architects. The building is meant to impress other avant garde architects, to make one?s reputation among ones peers, to get noticed by journals or academics. A new Boston style?a democratic rather than aristocratic style?would have as its audience the people of the neighborhood or city where the building is being made. This does not mean that the building needs to pander to the tastes of the crowd, to reproduce what the layman is used to, or to simply reach for the lowest common denominator. But it does force a change in the architect?s attention, to realize who this building is for, to stop considering the people of the neighborhood as mere philistines whom the architect is going to educate from on high. For example, H.H. Richardson?s Romanesque buildings were quite a departure from the existing status quo, but always had the attitude that they were there to serve the people who were going to use them, he never sneered at the tastes of his audience the way much so-called cutting edge architecture seems to.

Landscaping:

Landscape architecture has progressed little in the US since Olmstead. The goal still seems to be the recreation in reality of 18th and 19th century landscape painting. There have been some adjustments informed by the greater understanding of ecology?the banishment of invasive species for example. This movement must be pushed forward. A Boston style of landscaping should have as its point not the creation of a pastoral idyll, but the promotion of maximum biodiversity. For example, I remember reading of a courtyard that was being built in honor of a resident who was an avid birder. The plantings were chosen by what would be most attractive to different species of birds at different times of the year. This promotion of biodiversity should be norm and not the exception and the standard of beauty should be nature?s abundance, the pleasure derived from the perception thereof, and not the amusement park experience of wondering through a living idealized landscape painting.

Affect

Finally, a new Boston style, "Boston Neo-humanism," would re-examine what emotional affect the architect should have on the viewer. Whereas modernism always seeks to challenge the viewer, to confound expectations, or to cause awe, or anxiety, or at best to "intellectually challenge" the viewer through irony, confrontation, or even spite, there is a call for a new approach. I vote that the architect should always strive to produce buildings that the viewer would love.