You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Best Urban Shopping Area

- Thread starter ablarc

- Start date

underground

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jun 20, 2007

- Messages

- 2,390

- Reaction score

- 3

Here's my Devil's Advocate case for the Landmark Center:

1) It's businesses serve the community it's in. There's a Best Buy, a Bed Bath and Beyond, a movie theatre, etc. In other words, businesses that locals use often, not businesses that tourists to use infrequently.

2) It's next to transit. Yeah, yeah, there's also parking. Well hopefully that will go away when the circle is redesigned and that part of the Fenway starts to pick up. In any case, the parking's not huge and I'd bet the majority of customers walk or take the train.

3) It's mixed use. There are offices and retail. I'm not sure if there's residential (I think not), but at least the building has residences surrounding it (excluding up Brookline Ave.).

4) It's got ground level activity. There's stuff all along Brookline Ave. and you can actually see the activity the businesses create.

5) It's a beutiful adaptive re-use.

1) It's businesses serve the community it's in. There's a Best Buy, a Bed Bath and Beyond, a movie theatre, etc. In other words, businesses that locals use often, not businesses that tourists to use infrequently.

2) It's next to transit. Yeah, yeah, there's also parking. Well hopefully that will go away when the circle is redesigned and that part of the Fenway starts to pick up. In any case, the parking's not huge and I'd bet the majority of customers walk or take the train.

3) It's mixed use. There are offices and retail. I'm not sure if there's residential (I think not), but at least the building has residences surrounding it (excluding up Brookline Ave.).

4) It's got ground level activity. There's stuff all along Brookline Ave. and you can actually see the activity the businesses create.

5) It's a beutiful adaptive re-use.

Bookie ?Harvard Street is tops. You got your discount liquor, Mr. Music for used guitar, some bar rooms, bookie.

After 28 forumers have weighed in, Newbury Street is way out front with 24 votes, followed by Harvard Square and Copley Place/Pru with 12 each, and Coolidge Corner with 8. Downtown Crossing straggles in in fifth place with 6 votes. Forty years ago, Downtown would have been as far ahead as Newbury Street is today.

Ron Newman

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 30, 2006

- Messages

- 8,395

- Reaction score

- 13

And even Harvard Square has struggled with some loss of retailers, both local and chain. It has also been overrun by too many banks and ATMs.

People like me, who've watched it change over 30+ years, often complain that it has lost its local identity. But it's still much healthier than Downtown Crossing right now.

People like me, who've watched it change over 30+ years, often complain that it has lost its local identity. But it's still much healthier than Downtown Crossing right now.

Last edited:

It's like complaining that something's not perfect.People like me, who've watched it change over 30+ years, often complain that it has lost its local identity. But it's still much healthier than Downtown Crossing right now.

After 32 votes, bringing up the rear are Charles Street, Hanover Street, Harvard Street in Allston, and Quincy Market. The first three are neighborhood Main Streets, though Charles and Hanover have some attraction for outsiders. For a few years, Quincy Market would have won this poll; it would have scored ahead of Downtown, Harvard Square and (yes) Newbury Street. Now, it seems, it's strictly for tourists.

Beton Brut

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,382

- Reaction score

- 338

Now, it seems, it's strictly for tourists.

Does anyone have present-day data on the percentage of locally owned retailers at the Quincy Market? Does anyone recall what the place looked and felt like in 1978?

And, does anyone think that there's a correlation between the tourists adopting the place (and locals considering it a tourist trap) and the fact that the overwhelming majority of retailers would find a happy home in AnyMall, USA?

statler

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 7,938

- Reaction score

- 543

Well, I was 4 years old at the time, so... no. But I would love to hear other's recollections.Does anyone have present-day data on the percentage of locally owned retailers at the Quincy Market? Does anyone recall what the place looked and felt like in 1978?

And, does anyone think that there's a correlation between the tourists adopting the place (and locals considering it a tourist trap) and the fact that the overwhelming majority of retailers would find a happy home in AnyMall, USA?

Chicken or the egg?

Jane Jetson

New member

- Joined

- Oct 24, 2008

- Messages

- 84

- Reaction score

- 0

I don't think the problem of loss of local identity is restricted to Boston; I think it started with the rise of the malls throughout the country. Chains are everywhere now - how can a local clothing store compete with Banana Republic? Local identity now is provided by souvenir shops - you know where you are by the knickknacks.

Quincy Market? Does anyone recall what the place looked and felt like in 1978?

It was the apotheosis of good taste. It was a vision of a shining future.

With our Dansk utensils we would eat venison and quail on a field of purest Marimekko.

Served at room temperature, our brie would run and come garnished with a pear. Henceforth wheat crackers would abrade the membranes of our mouths.

Spartan would be the new luxury. We would cook like peasants in order to eat like kings.

All colors would be primary-bright, all materials honest and true. The world?s counters would be solid maple, and its wheelchair ramps clad by Pirelli. This would be a world where everything sparkled --from Dom Perignon to Christmas lights in trees.

You would be able to get a baguette just like the ones in Paris.

* * *

Though conceived and shepherded by an architect who knew his stuff, this would be a vision waffled out of the romantic vapors of Architecture without Architects; photomurals from Rudofsky?s quasi-seminal work graced stairwells and corridors of the great man?s atelier without anyone quite knowing why --though subliminally, it did sort of make sense.

In 1973, if repressed puritan fanatic Sayyid Qutb had lobbed a grenade through the basement window of a certain crenellated Tudor apartment house on Brattle Street?s northeast sidewalk, he would have scored a direct hit on the command post of all that he hated. For here was sequestered the platoon specially assembled to propel America?s taste in consumer goods to heretofore unimagined pinnacles of materialism --in surroundings slyly disguised as heritage of the past.

And here stalked --at once Impresario, Pygmalion and Svengali of his brave new world of material well-being --the redoubtable, the nonpareil, indeed the Master of his universe, the incomparable Benjamin C. Thompson.

?Probably no other architect of his time did more to change the face of America than Benjamin C. Thompson.? --Robert Campbell

Founding-partner-fresh-out-of-school of The Architects Collaborative starring Walter Gropius, wizard of Design Research, sower of the Harvest Restaurant and a half-dozen others of its ilk, Ben?s greatest creation by far was that delirious concoction of tanned faces and sleek bodies, medjool dates and smoothies, pushcarts and boutiques, jugglers and clowns, baguettes and baklava that a phrasemaker in Rouse?s front office eventually dubbed the Festival Marketplace. And the first one was conceived and sprang upon a world panting for the future of retailing right here in Boston! (?that ongoing architectural hotspot?)

(A cynic would see that Thompson was a running dog for the kitsch of Martha Stewart. To go from one to the other, you just had to switch the source of your draperies to Liberty of London.)

I can?t tell you exactly how adrenaline smells, but like a dog, I have the ability to sense it in the air --and Ben?s basement platoon positively reeked of adrenaline. Minions arrayed in rows anxiously awaited Ben to meander --or his wife Jane to stalk-- down the aisle between the drafting tables.

Jane sometimes bore pink slips, but with personable Ben came his latest inspirations: grains of sand to be dutifully documented in words and drawings, then assembled secretarially into ring binders full of shalts and shalt-nots arranged by topic. After thousands of pages of words and sketches, a mountain emerged from those grains of sand, and it penetrated the clouds.

What was coming into focus dwarfed even today?s building or zoning codes in magnitude and thoroughness. Nothing was left to chance, for here was Ben?s blueprint for the cosmos. It was the concept ? the dream ? THE VISION. And Ben was the prophet.

By imagining the future, Ben was simultaneously creating it.

He conjured it directly out of his fastidious brain. And he invited us to join him in its cultivated confines.

The future: its defining characteristic would not be flying cars or jet packs, nor sky bridges between the 100th stories of buildings, nor even African-American presidents presiding over a nation of straight and gay mixed couples. No, the defining characteristic of the future would be that ? EVERYBODY WOULD HAVE GOOD TASTE!!

All corkscrews would be Italian and demonstrate different obscure principles of physics.

There would be no borrowed glory, no formica that tried to look like marble, or vinyl aping walnut.

No Bordeaux would be quaffed before its time, and the Mouton Cadet would come out only when folks were too sloshed to notice.

There would be no chains, or at most small local chains?

* * *

It was an awful lot for James Rouse to swallow and digest, and often he gagged. It required constant renewal of his faith, constant stoking of the fires of belief, and a deaf ear to the constantly-expressed expertise of his marketing guys.

He?d agreed to the concept in a rash moment; he had turned his back on the experience that told his developer?s mind that you couldn?t turn this expiring, fly-infested, third-world, semi-wholesale meat market into a runaway moneymaker. He didn?t know what had gotten into him, and he wished he could back out of it or at least do a shopping center the way he knew how to do a shopping center.

This chimera of Thompson?s, this bubble?

He liked historic buildings to be saved as much as the next guy, but not on his investors? ticket.

Though Ben wasn?t really born with the gift of a golden tongue, he saw to it that everyone who worked for him could draw like an angel. That helped sell his ideas. For the official poster, Carlos Diniz produced a rendering so breathtakingly detailed that it rivaled ?Where?s Waldo?? You could find it somewhere on the walls of nearly every young architect?s apartment in the year leading up to the opening.

Rouse knew you couldn?t implement an artist?s notion till you?d tamed it with plentiful helpings of common sense and business know-how. It was only thus he had allowed himself to develop Columbia, Maryland, once a fantastic pipedream that you could build a walkable new community --in the second third of the Twentieth Century!

He had fixed that one with parking lots, but he sometimes wondered if it had been worthwhile financially or if he would have made just as much or more money with a development less hamstrung by notions of design. Then he looked at his wall of plaques and certificates from planning societies and universities ? and all those invitations to lecture ?

(Truth is, however: if not for the overdesigned sign posts and traffic lights, you might not know today in Columbia that you were in a place that was supposed to be different and utopian.)

But this Thompson: on many matters that impacted the budget, he simply refused to budge. He had this concept?

* * *

When my family moved to Boston from the Midwest, I found a city of mystery, slightly grim but boundlessly explorable. It promised a reprise of the happy months I?d scouted nooks and crannies of Paris as a child of the Metro. I was sort of an urban spelunker.

In Boston, there were sun-dappled sidewalks to explore beneath screeching trains, streetcars that ran in tunnels, vast, dirty, glass-vaulted sheds for transferring from subways to buses at Dudley and Sullivan, electric buses that whooshed recklessly underground into Harvard station; and the station names rang euphonious with now dimly-remembered places: Boylston/Essex, Winter/Summer/Washington, State/Milk/Devonshire, Haymarket/Union/Friend (Union/Friend [!]), Everett, Thompson Square, City Square, Devonshire, Dover, Northampton, Dudley, Egleston, Massachusetts, Mechanics? Mechanics [!]

At night, the fishing fleet bobbed like an algae bloom in the basin between Long and Commercial Wharves. Bars abounded, well-patronized by uniformed sailors who were mostly as they should be on shore leave: drunk. Military police patrolled in Jeeps.

And once I personally observed what I thought happened only in movies: a door burst open with a blast of light, beer fumes and loud laughter; and propelled by a burly bouncer with one hand on the seat of his pants the other on the scruff of his neck, a rag-doll sailor performed a perfectly elliptical trajectory through the air to land upon his sacrum among the cobbles.

It seemed it was always raining.

The south side of Long Wharf was solid to the pier line with ramshackle residences, two stories, yellow-tin-clad and enlivened with window-box geraniums (damned if they didn?t all have them!). I think some of the fishermen lived there.

There was City Square and its police station, filled with the screech of the Elevated and the promise of late-night crime?

And there was Quincy Market. My guilty pleasure was to sneak through the spring-loaded flapping wood doors into the temple of gloom. There, lit by naked light bulbs and unhinged fluorescents, sporadic carcasses in various states of disassembly hung from hooks along the nave. Vertical strips of heavy transparent vinyl did little to deter the flies from their feasting and other functions.

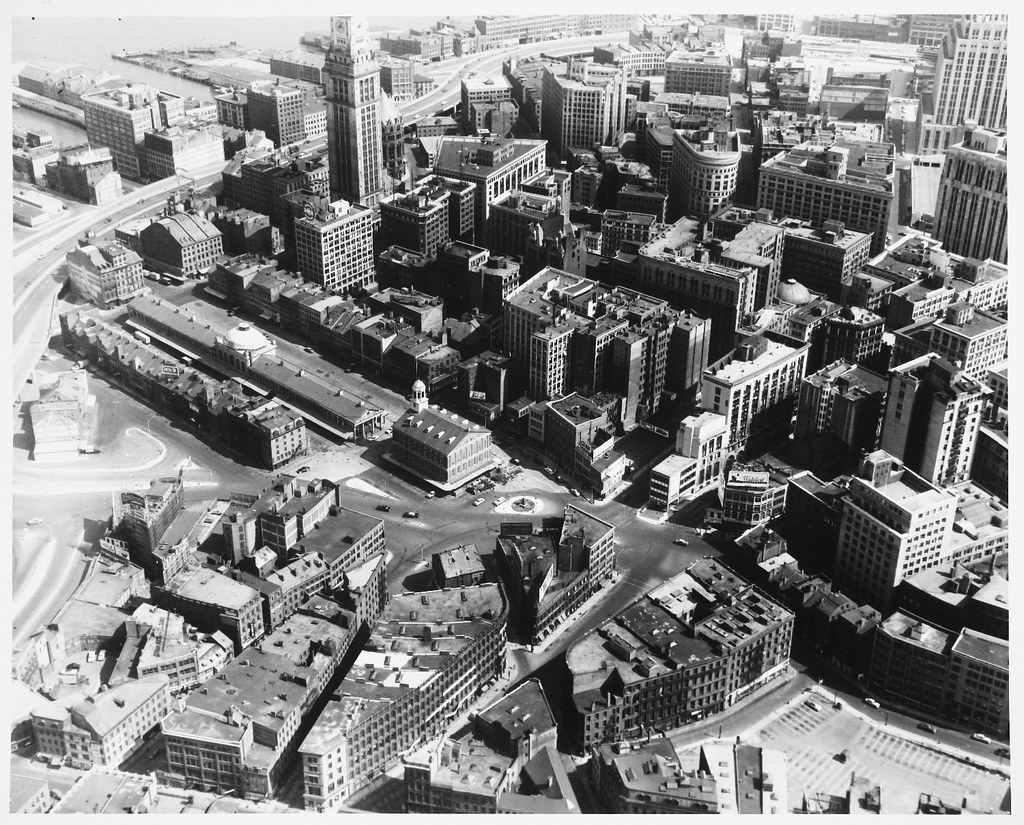

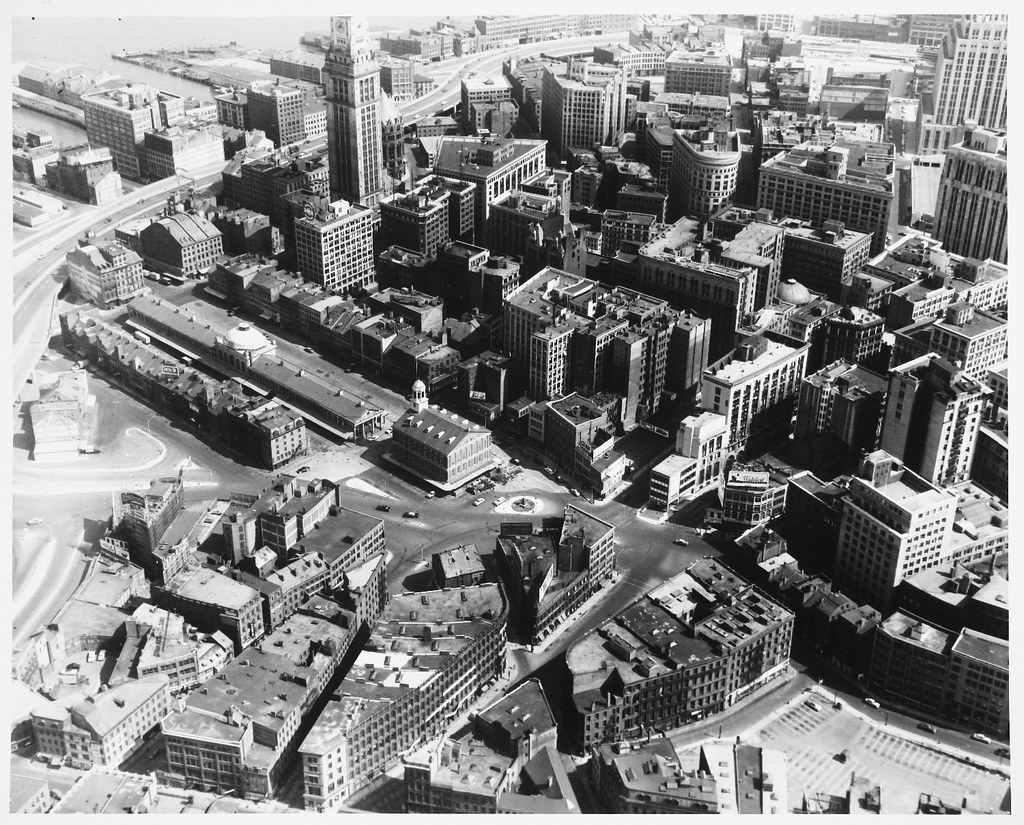

Market before Thompson and Rouse.

At most a third of the stalls were occupied. The owner?s names were emblazoned on professionally hand-painted signs, and they would slice off pieces of the carcass to suit your needs. Prices were lower than the Stop and Shop, and restaurants bought here.

At noon, the men trooped off to Durgin-Park in their bloody aprons.

* * *

Periodic suggestions were made to level Quincy Market. The area needed parking, and that seemed like a logical place. At that time there was even a down ramp from the elevated expressway; here a parking lot would have made good money. I think someone tried a fire but, uninformed, the firemen got there too soon and put it out.

Architects and historians could see the buildings were priceless underneath the grime and neglect: solid granite and masonry in the finest Greek Revival style. Ben Thompson decided this would be his project. He got Rouse on board, because that old softie had public-spirited aspirations; he somewhat resembled Charles Coburn.

Then as now, the Boston area was full of architects. They hung around because the city had architecture both old and new. The new stuff turned them on even more than the old; Boston was a place of pilgrimage for the world?s architects. Though pilgrims came from Copenhagen, Helsinki, Stockholm and Milan to gawk at Boston?s modern monuments by Sert, Pei, Corbu, Rudolph, Kallmann, Saarinen, Gropius and Aalto, Boston?s local boys were staunchly Eurocentric. They could see that City Hall was La Tourette, Christian Science merely cut-rate Chandigarh, and that Kresge was really by Nervi.

Not least among the Europhiles was Thompson. He packed D/R with stuff from Milan and Helsinki and plotted the transformation of American taste. The future held double-expressos in place of Maxwell House, camembert instead of Velveeta and Bass Ale where there had been Bud. Salads in Ben?s restaurants were dressed in vinegar and oil; no goopy ranch dressing to be found. Oh, and where?s the iceberg? Look Honey, there?s no iceberg in our salad, just stuff that looks like dandelions or something?

In Cambridge and parts of Boston, folks were already hip. They knew that persimmon, olive and other ?designer? colors weren?t cool, they preferred the Door Store or even Goodwill for their furniture, and they drove wheezy or ?practical? Swedish cars. When it came to beverages, they had discovered both St. Pauli Girl and Chateuneuf-du-Pape.

Problem was: they had no place to congregate to worship their newfound consumer credo, no place to flash their Movados and flaunt their sheepskin jackets.

Enter Ben Thompson.

He had a concept.

And it dovetailed perfectly with the yearnings of the hip, the preppy, the Eurocentric, the Bohemians, the educated, the tastemakers and the architects. (No one used the term at the time, but these were the folks we?ve come to know as ?yuppies.?)

Ben?s concept was elitist. He said there are folks in the know, and there are folks who are rubes. And he would set about turning the second group into the first, and he would make those folks happy while he did it, and he would make all sorts of people rich.

Annually, he would stage little demonstrations of connoisseurship at his home on the Cape. No one, but no one, ever turned down an invitation to one of his Cape Cod shindigs. So there were hundreds of people on hand, and they all got a lobster and all the bubbly they could hold. I wonder how many accidents he caused.

With the help of the ring binders full of specifications, the concept of good taste was grafted onto the three main buildings of Quincy Market.

There was a debate within the firm about what historical authenticity meant in the context of Quincy. You see, South and North Market buildings had been developed over time as numerous tiny incremental parcels with individual property lines and deeds; as a result, the master plan for these buildings was never fully realized as conceived by the original architect, Alexander Parris, in Greek Revival times.

So there were now taller buildings, a few Second Empire mansards, a little Deco and even a miniature skyscraper of about seven stories. Also, some of the arched granite shop fronts had been replaced by newfangled cast iron or steel structure that allowed more glass.

In the end, it was decided to ?restore? the buildings to a condition they had never actually seen: the architect?s original concept with uniform units. But even this concept was somewhat compromised by retention of a couple of cast iron fronts that make a nice counterpoint to all those granite arches; also, Durgin-Park was allowed to remain dirty and undisturbed --and a fire hazard.

As word got around, you wouldn?t believe the anticipatory buzz. People couldn?t wait, because they could tell that this place was going to be wholly unlike anything that had been seen before. Long before anything was open, folks swarmed over the construction site to inspect. The Holy Grail was about to be found, and Ben was the Messiah.

When it finally opened, it didn?t disappoint. It delivered even more than it had promised. Ben and his ringbound regulations had seen to that.

There wasn?t anything ordinary to be found. If there was ground beef, you?d find it in a pita.

There wasn?t anything phony to be found. If it looked like granite, it was granite. Even the coke was dispensed from fountains that eschewed the woodgrain vinyl.

There was not a backlit vinyl sign to be seen.

Except for the light troughs that lined the nave, all indoor lighting was incandescent, directed and shielded. Outdoor fixtures came straight from Tivoli Gardens, and the trees featured unseasonal Christmas lights.

All the knickknacks sold from puschcarts were interesting or handmade or both.

The bars had piano players and sleek hostesses in short skirts, and the taps dispensed Beck?s.

Girls wore sunglasses pushed up into their hair, St. Tropez-style: barrettes gazing at heaven. They all had tans, and the guys wore their Gucci loafers without socks. They hung around till midnight, whooping and staggering to the subterranean loos.

The under-thirties mobbed this place from day one. After a while, a few of their elders happened in from the suburbs. It was better than they thought.

For that final touch of authenticity and a veneer of continuity, Ben had persuaded Rouse to keep a few of the best meat dealers at subsidized rents and with sanitary glass-fronted meat lockers; ditto some cheese merchants. So you could pick up your week?s supply of filet mignon and gorgonzola.

In fact, Ben had rigged the tenant mix so you could still think of this place as a food market if you chose to. You could actually do your week?s grocery shopping here if you could afford the prices. You could even buy fruit, and there were Turks who sold spices.

A greasy spoon that had fed breakfast to the butchers was also retained, though it was made to clean up. (Can?t remember the name, except it was a woman?s first name.) Since it was the only standard American comfort food in the whole place, it seemed themed.

Out in the open just to the east of the Food Court, a little pointy-nosed guy with a severe language barrier wowed everyone with his skill at cutting dough before it went in the oven. What came out was Boston?s very first genuine French baguette and an equally pioneering croissant. The sign over the Frenchman?s head read ?Au Bon Pain.?

Where is he now, and can you get even a half-decent baguette at the chain that grew out of his efforts?

The rubes didn?t know what to make of it. They searched in vain for something familiar to eat. There were no glazed donuts, so they reluctantly sprang for a $2 chocolate croissant, and found they liked it.

As the years wore on, there got to be more rubes, and as management relaxed Ben?s rules, the Gucci crowd gradually decamped to Newbury Street, the chains moved in as the place changed hands, and I bet now there?s even woodgrain vinyl. North and South Building, at first united at upper levels by access corridors for upper level stores full of truly glitzy merchandise have lapsed into mediocrity and non-retail uses.

Now if you want to see a collection of truly obese people in Boston, you know where to go. It seems like all of West Virginia has come here to tour the sophisticated city.

Is there anything left of Ben?s vision?

Ben, the tastemeister?

What do bears do in the woods?And, does anyone think that there's a correlation between the tourists adopting the place (and locals considering it a tourist trap) and the fact that the overwhelming majority of retailers would find a happy home in AnyMall, USA?

I think, however, that what you think is the cause may actually be the effect.

statler

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 7,938

- Reaction score

- 543

Thanks for the history lesson ablarc. You paint a picture a vivid as any of the photos in this thread.

Are there even enough local stores and chains left to fill Quincy Market even if they wanted too?

1959:

Are there even enough local stores and chains left to fill Quincy Market even if they wanted too?

There was a debate within the firm about what historical authenticity meant in the context of Quincy. You see, South and North Market buildings had been developed over time as numerous tiny incremental parcels with individual property lines and deeds; as a result, the master plan for these buildings was never fully realized as conceived by the original architect, Alexander Parris, in Greek Revival times.

So there were now taller buildings, a few Second Empire mansards, a little Deco and even a miniature skyscraper of about seven stories. Also, some of the arched granite shop fronts had been replaced by newfangled cast iron or steel structure that allowed more glass.

1959:

Last edited:

blade_bltz

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 9, 2006

- Messages

- 808

- Reaction score

- 0

Nowadays, does any sane person buy into a 'vision of a shining future'? (In this country, not China).

Good taste, as you've described it, is synonymous with 'Elitist', and that's on a par with 'Pinko' on the taboo scale.

Anyway, what else are the Tourists supposed to do? You think all those West Virginians can really sustain themselves on Colonial history for an entire vacation? (In this economy, what West Virginians???)

Non-rhetorical question: did legitimate tourism even exist in Boston during the post-war decades?

Good taste, as you've described it, is synonymous with 'Elitist', and that's on a par with 'Pinko' on the taboo scale.

Anyway, what else are the Tourists supposed to do? You think all those West Virginians can really sustain themselves on Colonial history for an entire vacation? (In this economy, what West Virginians???)

Non-rhetorical question: did legitimate tourism even exist in Boston during the post-war decades?

What's legitimate tourism?Non-rhetorical question: did legitimate tourism even exist in Boston during the post-war decades?

I assume you're excluding an excursion from Worcester to catch a show at the Old Howard.

They hadn't installed the red line of the Freedom Trail, and I'd guess many Americans would have found both North End and South End to be menacing.

There have always been folks, however, who just liked to explore cities. Boston was a good one to explore, since it had so many hidden places. Not so much anymore; it's the price you pay for big vistas and big buildings.

You want a hidden place? Seek out Ida's in the North End for a great, cheap, old-fashioned dinner. No website. Not a place a tourist would go.

What keeps them in business? Regulars.

Local chains Nedick's, Sharaf's and Waldorf in nearby Scollay Square, ca. 1955, click to enlarge:Are there even enough local stores and chains left to fill Quincy Market even if they wanted too?

Chains went global, along with everything else. Might that be partly reversed in the future?

Ron Newman

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 30, 2006

- Messages

- 8,395

- Reaction score

- 13

With that big blank brick wall, I bet the building on the right is a theatre. Which one?

Beton Brut

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,382

- Reaction score

- 338

Thanks, ablarc, for a thoughtful, nuanced response to a couple of cast-off, snarky rhetorical questions last week.

This struck me:

Rich indeed. I'm a child of the 70's, and my folks, though not rubes, spent the 6o's listening to Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, and Jerry Vale. Their first experience with "designer goods" was likely due to Ben Thompson. So too, my ensuing love of industrial design began in the windows of Crate & Barrel, blown away by Artek objects and furniture.

Wouldn't it be nice...

Relaxing Ben's rules clouded his vision to the point that if you squint, Quincy Market is only a mirage. It's too simple to say that the festival marketplace (as a concept) is a victim of its success. It's spawned a myriad of half-assed knock-offs, positioned as "lifestyle centers" that sell consumerism as a substitute for quality merchandise.

I've said before, my first real experience of "Architecture" was Boston City Hall. My first taste of human aspiration, of wanting to live better than my folks, was likely inside of Ben Thompson's vision. I miss it. Most Bostonians don't even know it's gone...

This struck me:

ablarc said:Ben?s concept was elitist. He said there are folks in the know, and there are folks who are rubes. And he would set about turning the second group into the first, and he would make those folks happy while he did it, and he would make all sorts of people rich.

Rich indeed. I'm a child of the 70's, and my folks, though not rubes, spent the 6o's listening to Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, and Jerry Vale. Their first experience with "designer goods" was likely due to Ben Thompson. So too, my ensuing love of industrial design began in the windows of Crate & Barrel, blown away by Artek objects and furniture.

ablarc said:No, the defining characteristic of the future would be that ? EVERYBODY WOULD HAVE GOOD TASTE!!

Wouldn't it be nice...

ablarc said:Now if you want to see a collection of truly obese people in Boston, you know where to go. It seems like all of West Virginia has come here to tour the sophisticated city.

Is there anything left of Ben?s vision?

Relaxing Ben's rules clouded his vision to the point that if you squint, Quincy Market is only a mirage. It's too simple to say that the festival marketplace (as a concept) is a victim of its success. It's spawned a myriad of half-assed knock-offs, positioned as "lifestyle centers" that sell consumerism as a substitute for quality merchandise.

I've said before, my first real experience of "Architecture" was Boston City Hall. My first taste of human aspiration, of wanting to live better than my folks, was likely inside of Ben Thompson's vision. I miss it. Most Bostonians don't even know it's gone...

Y'welcome; didn't realize the question was snarky; thought you just wanted to hear from someone who was there.Thanks, ablarc, for a thoughtful, nuanced response to a couple of cast-off, snarky rhetorical questions last week.

Coulda done worse.Rich indeed. I'm a child of the 70's, and my folks, though not rubes, spent the 6o's listening to Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, and Jerry Vale.

Ain't that the truth!Relaxing Ben's rules clouded his vision to the point that if you squint, Quincy Market is only a mirage. It's too simple to say that the festival marketplace (as a concept) is a victim of its success. It's spawned a myriad of half-assed knock-offs, positioned as "lifestyle centers" that sell consumerism as a substitute for quality merchandise.

Most Bostonians don't know it was ever here.My first taste of human aspiration, of wanting to live better than my folks, was likely inside of Ben Thompson's vision. I miss it. Most Bostonians don't even know it's gone...