Chris and Stellarfun, your thoughtful, intelligent questions overlapped a lot, so I combined the answers in this Q&A.

Q-1. Can air pollution be avoided in air rights development?

A-1. Yes. All I-90 and I-93 air pollution can be treated using technology identified during the Big Dig begun in 1984, and during New York?s World Trade Center site work begun in 2001.

Q-2. What happens to the air pollution?

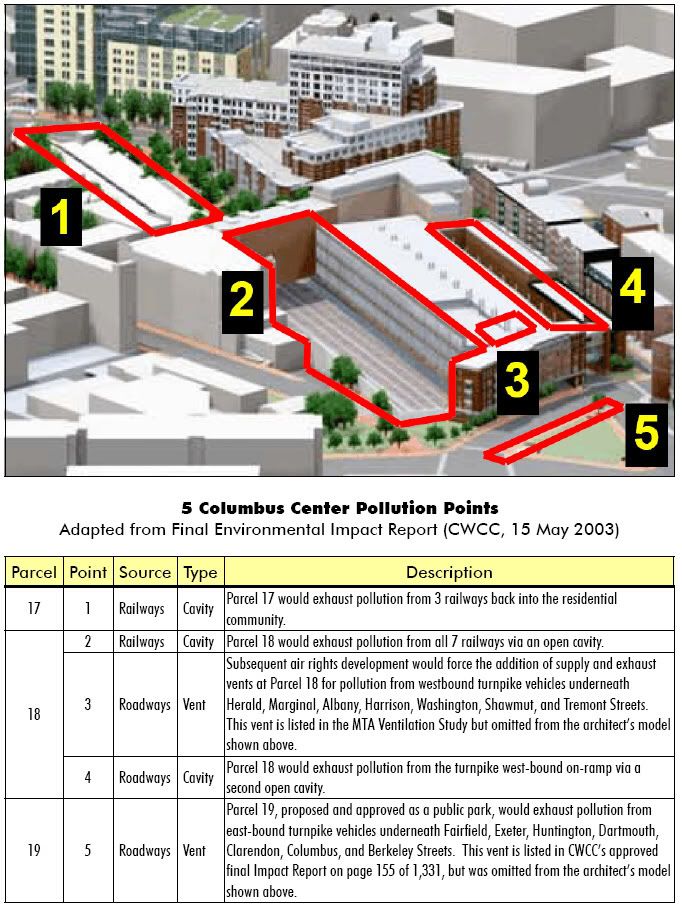

A-2. It?s exhausted back into the communities. Four years ago, MTA, BRA, and the owners of Columbus Center decided to build at least 15 exhaust vents (12 mechanized + 3 non-mechanized) to capture, concentrate, and return all air pollution from the 14 rail way and road way tunnels below ? untreated ? back into the communities above. The average turnpike fan will deliver 577,273 cubic feet of highly concentrated toxic air per minute, creating a cross-town public health crisis. They kept this decision secret until after the Columbus Center public hearings were finished. I?ve illustrated here the 12 mechanized vents (red rectangles) and their impact areas (pink circles), using a map from the Master Plan, vent locations from the MTA vent study, and impact area diameters based on thousands of studies on file at the National Library of Medicine.

Q-3. Why doesn?t covering the transportation corridor end the pollution?

A-3. Concealment doesn?t constitute cleansing. Visually covering some pollution points did generate some pretty watercolors painted from safe angles, but exhausting 100% of the concentrated, polluted air back into the communities prevents any air quality improvement.

Q-4. Does the Master Plan consider turnpike air pollution a problem?

A-4. Yes. On PDF page 39, under ?goals for the corridor?, the Master Plan states, ?Protect the residential neighborhoods from transportation-related noise and air-pollution.?

Q-5. Does the Commonwealth consider turnpike air pollution a problem?

A-5. Yes. On 18 March 2003, the Secretary of Environmental Affairs issued a 15-page ?Draft Environmental Impact Report Certificate #12459-R? that required the developer to disclose the then-secret MTA vent study, ?Conceptual Ventilation Study for the Civic Vision for Turnpike Air Rights in Boston? and to report on those findings regarding air rights development over the transportation corridor. The developers withheld the MTA vent study for years, and when EOEA-MEPA forced its disclosure, the developer buried it on page 891 of a 1,331-page impact report released on 15 May 2003, after public hearings had ended, to ensure it wouldn't be discussed. But the vent study didn?t inform the public as the Secretary had prescribed, and today, over four years later, even members of this forum remain unaware of the issues it presents.

Q-6. Does the federal government consider turnpike air pollution a problem?

A-6. Yes. The Clean Air Act of 1990 requires protection for ?susceptible populations.? The latest study, from Tufts University dated 9 August 2007, concludes that all near-highway residents ? everyone living in Boston?s air rights neighborhoods ? are susceptible populations. [An abstract and the full report are at

www.EHJournal.net/content/6/1/23 for viewing an downloading.] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency?s National Ambient Quality Air Standards Manager, Dr. Karen Martin, stated at the July 2007 federal conference on particulate matter that the Clean Air Act requires that such communities receive ?health protection with an adequate margin of safety.?

Q-7. Are the owners keeping their promises to end air pollution?

A-7. No. Columbus Center?s new owner testified to Boston City Council that all of the fumes would be ?hermetically sealed below the site.? In fact, there are no airtight seals at all; none were proposed, none were approved, none are planned, and 100% of today?s and tomorrow?s air pollution would be exhausted ? untreated ? into residential communities. The new owner's testimony can be seen in the videotape of Boston City Council?s Committee Hearing on Planning & Economic Development, Docket 0524, 5 May 2006, around minute #14, at

www.CityofBoston.gov/CityCouncil/cc_Video_Library.asp?id=197.

Q-8. Does the Master Plan require a park?

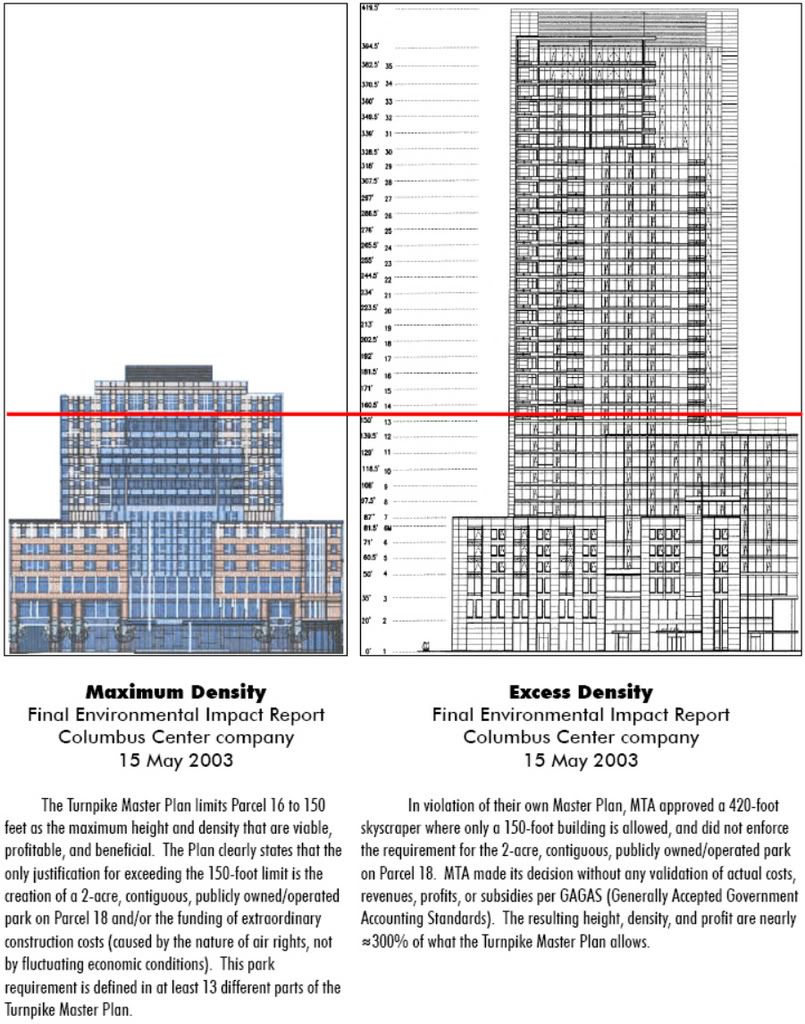

A-8. Yes. PDF pages 1, 15, 17, 80, 83, 84, 90, and 91 in the Master Plan illustrate that whenever the Parcel 16 tower exceeds 150', there must be a single, contiguous, 2-acre public park to compensate. The new owners insist upon a 420-foot skyscraper, so the 2-acre park is required, yet they replaced that park with a 633-car garage.

Q-9. What?s the difference between a single, contiguous park and multiple smaller parks?

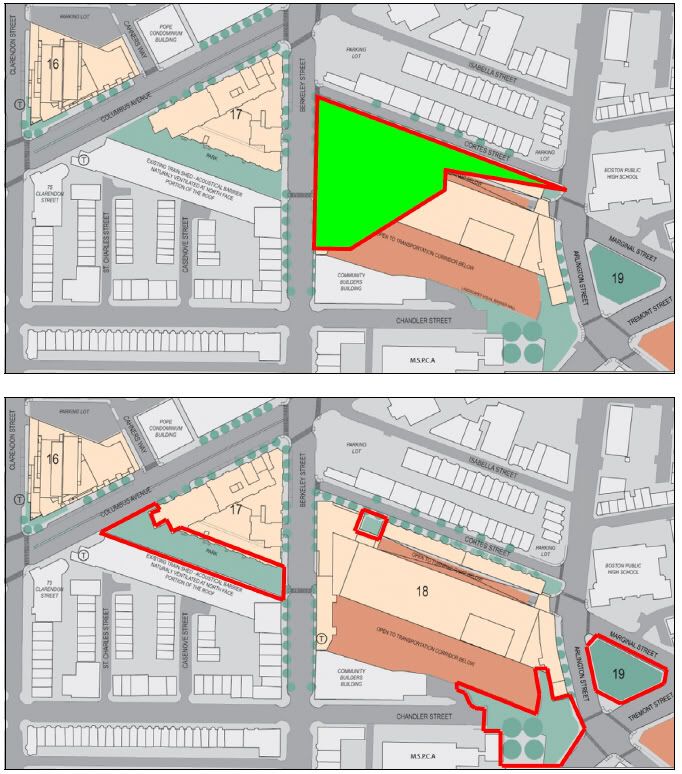

A-9. Plenty. The sum of one contiguous park is superior to the total of four smaller ones on different streets, because chopping up the square feet diminishes the benefit, as shown in these public domain images adapted from the proposal.

Q-10. Is anyone opposed to Parcel 19 as open space?

A-10. No. There?s no public record of anyone opposing the Parcel 19 Park-ette. Unfortunately, the urban oasis for children, seniors, and pets portrayed by the pretty watercolors will never materialize, because Columbus Center alone has 5 air pollution exhaust points.

Q-11. Is there proof that the promised public parks are now private gardens?

A-11. Yes. In their 1,100-page, 99-year lease signed 2 May 2006, the new owners and MTA privatized 3 new parks totaling 37,350 s.f. This broken promise was questioned by the Metropolitan Highway System Advisory Board, a statutory agency created by the legislature to review all air rights development contracts. In his 9 March 2006 response, MTA attorney Steven Charlip wrote to MHSAB, ?All Columbus Center open space will remain in private ownership? and ?the MTA will have no obligations related to parks.?

Columbus Center refers to the open space as ?state parks for the public?; however, the condominium owners decide when, how, and to what extent they will open, close, secure, operate, and maintain their privately owned green spaces. Nothing prevents them from re-defining their private gardens and expenses in ways contrary to the standard definition of ?public park.? The general public has no recourse.

Q-12. What was the bid process?

A-12. There was none. On 31 January 1997, MTA Chairman James Kerasiotes gave Columbus Center?s former owners a perpetual guarantee that: (1) they would face no competition; (2) if any competing proposal arose MTA would refuse it; (3) they would face no financial disclosure, and (4) they would pay only penny-on-the-dollar rent (about 1% of fair market value). The Framingham Service Plaza gas station and fast-food grill now pays MTA

$12 million per year, but Columbus Center would pay only

$12 million per century.

Q-13. Isn?t the 99-year lease less valuable than an outright sale?

A-13. No. On 6 March 2006, MTA purchased an independent, professional, fair-market-value property appraisal from Lincoln Property Company. On PDF page 96 of 120, appraiser Steven Foster wrote that the characteristics of the no-bid, no-disclosure, no-risk, sweetheart deal rendered any potential difference between the 99-year lease and an outright sale ?negligible.?

Q-14. When did the former owners sell to the new owners?

A-14. The Columbus Center project and company were sold 1.5 years ago. Columbus Center was first proposed on 18 December 1996 by Boston-based Winn Development, which for the next 11 years used over fifty different names for the venture. On 15 March 2006, Winn sold out to a 3-tier California investor:

? owner: CalPERS (?California Public Employees Retirement System, A Component Unit of the State of California?)

? subsidiary: CUIP (California Urban Investment Partners, a wholly owned subsidiary of CalPERS)

? consultant: MacFarlane Urban Realty Company (hired by CalPERS to manage its CUIP investments)

CalPERS now has majority ownership and control. It was CalPERS that executed the 99-year lease with MTA. As a sub-contractor to CALPERS, Winn retains only a small share of profits and losses, and has no independent control.

In 2006, CalPERS committed $145 million to the project, but then wrote to Commonwealth officials that the project was insolvent without a looser lease, lower rent, and larger subsidies. The new California owners want the Massachusetts public to subsidize both the costs and the profits for a project they now claim costs $800 million.