Columbus Center questions

Wilkerson's ties to developer and business community fall under federal scrutiny

By Casey Ross

Globe Staff / November 23, 2008

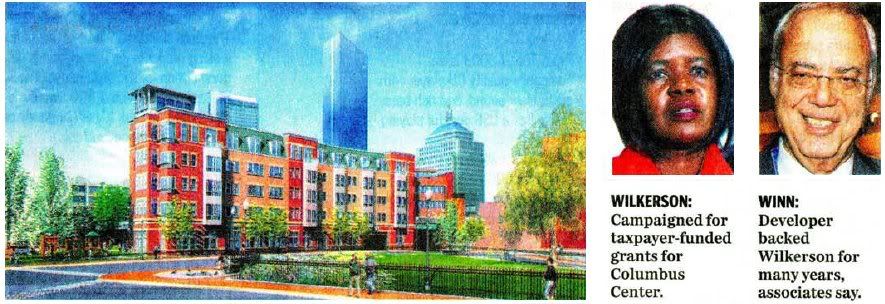

The federal subpoena arrived at the office of developer Arthur Winn soon after the arrest of then-state Senator Dianne Wilkerson last month.

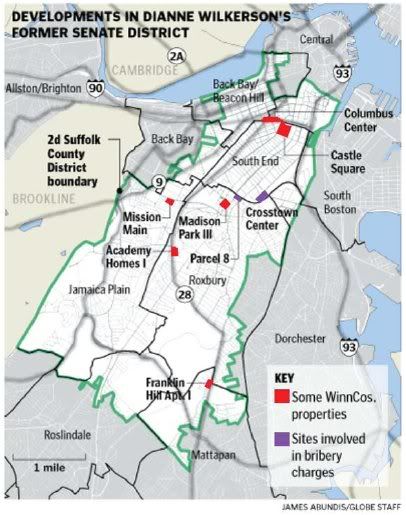

Graphic Development in Dianne Wilkerson's former Senate district

Winn was among the former senator's earliest and most ardent political supporters. Their politics were different: he, a wealthy Republican; she, a liberal Democrat. Still, Winn and his business associates contributed more than $18,200 to her campaign account since 2002, according to state records.

The developer and politician had common policy interests: affordable housing and public subsidies for the $800 million Columbus Center project in Boston.

Wilkerson has been a vocal backer of Winn's most ambitious and luxurious project, waging a campaign to win more than $70 million in taxpayer-funded grants and low-cost loans even as community members and fellow legislators opposed the subsidies.

Winn's firm, WinnCompanies, received a subpoena from federal authorities on Oct. 28, one of many sent to government leaders and business executives as part of an 18-month investigation of Wilkerson by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Neither Winn nor any of his developments were referenced in a 32-page federal affidavit outlining public corruption charges against the former senator, and he has not been accused of any wrongdoing in connection with the case. But his subpoena shows that investigators are examining Wilkerson's contacts with powerful figures who worked closely with her on a range of government business.

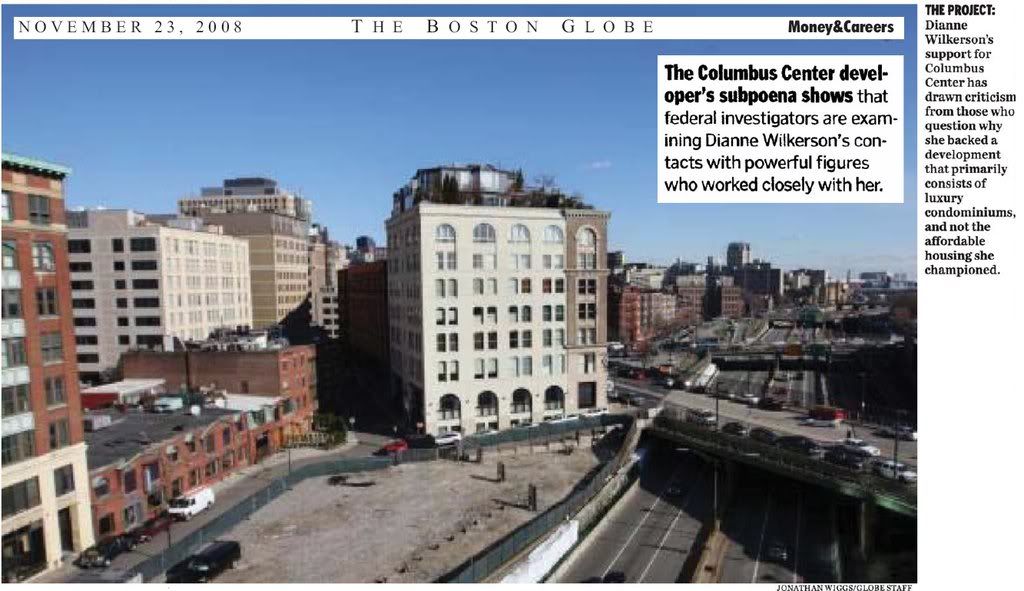

Columbus Center - a condominium, hotel, and retail development - is the most prominent project where Winn and Wilkerson intersect.

Her public advocacy of public subsidies for the project began in 2005. Federal authorities began investigating Wilkerson in early 2007 and allegedly caught her taking eight bribes totaling $23,500 from an FBI informant and an undercover agent. The affidavit accuses her of taking payments in exchange for securing a coveted city liquor license and crafting legislation paving the way for a development in Roxbury.

Wilkerson, who resigned from the Senate last week after being formally indicted, did not return multiple phone calls, and her at torney Max Stern, declined to comment. US Attorney Michael Sullivan has said the investigation remains active and that additional charges will be filed if called for by the evidence. On Friday, federal agents arrested City Councilor Chuck Turner on charges he accepted a $1,000 bribe.

Winn, through a spokesman, declined to comment for this story.

Wilkerson's support for Columbus Center, back then and now, drew questions from opponents who wondered why she so strongly backed a development that primarily consists of luxury condominiums, not the affordable housing for low-income constituents she championed.

"We didn't understand it," said state Representative Marty Walz, a Back Bay Democrat who opposed subsidies for Columbus Center. "She seemed intent on getting taxpayer money for the project, but no one really knew why it became such a priority."

In prior interviews with the Globe, Wilkerson touted the project's potential for creating jobs within her district, pledging to go after "every pot and every pool of money" to assist the development, which has been hotly debated since it was proposed in 1996.

Graphic Development in Dianne Wilkerson's former Senate district

Her relationship with Winn predates Columbus Center, stretching back more than 15 years, to when she first became involved in politics and was elected to the state Senate in 1993. Winn regarded Wilkerson as an articulate politician who could be an effective advocate for her district, according to business associates of Winn.

Both championed affordable housing. Winn, the largest provider of affordable housing in New England, currently manages more than 30 developments within Wilkerson's former district, which includes the highest concentration of subsidized housing in the state. He has used public subsidies to rehabilitate many of them, including the 532-unit Mission Main complex in Roxbury and the Castle Square development in the South End.

Since 2002, Winn and his business associates have contributed more than $18,200 to Wilkerson's campaigns, including $2,000 at a June 18, 2008, fund-raiser at the Bostonian Hotel that was attended by an undercover FBI agent who was investigating Wilkerson, according to state records and the FBI affidavit. Under state law, an individual can give a maximum of $500 to a public official in a calendar year.

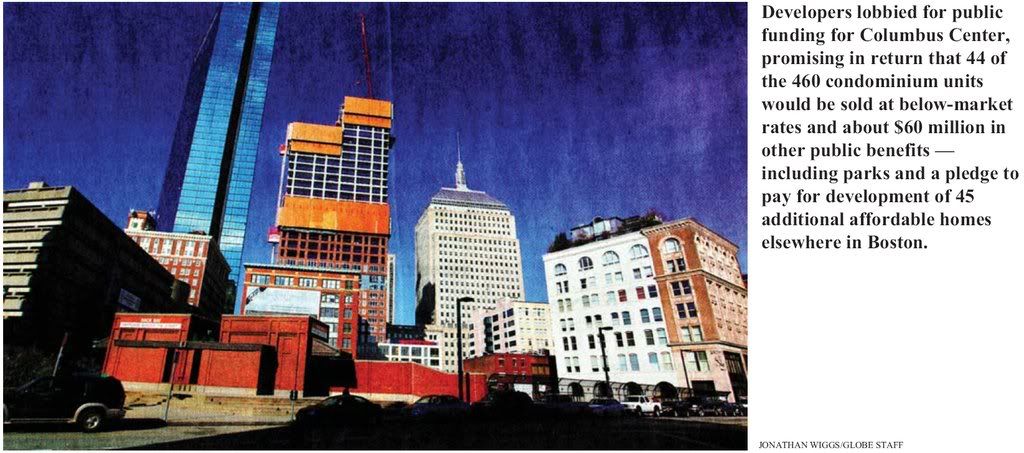

Columbus Center includes some affordable housing - 44 of 460 condominium units are to be sold at below-market rates, but it is primarily being marketed as an upscale development featuring a hotel and shops. The project also promises about $60 million in public benefits, including parks and a pledge to pay for development of 45 additional affordable units to be located elsewhere in the city.

Officials in Mayor Thomas M. Menino's administration have supported the project, both because of its economic development potential and its ability to knit together the South End and Back Bay neighborhoods. The project received final approval from the Boston Redevelopment Authority, the city's planning arm, in 2003, and top officials began backing attempts to get taxpayer subsidies to assist the project.

"It's our sense that these public monies are the only way this project is going to get off the ground," Harry Collings, then executive secretary of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, said of Columbus Center in an interview with the Globe last year. "We feel the benefits far outweigh the public money's participation."

Among those who worked with Winn to gain support from the city was Stephen V. Miller, a politically connected Boston lawyer known for his work in licensing and development, as well as for his fund-raising efforts on behalf of city politicians.

The subpoena sent to Winn asks for his communications with Miller, who was identified by the Globe as a lawyer referenced in the FBI affidavit outlining the charges against Wilkerson

In the affidavit, Miller is described as helping Wilkerson obtain a city liquor license for a confidential informant working with the FBI. The informant, whom the Globe identified as Ronald Wilburn, allegedly gave Wilkerson thousands of dollars for her help in getting the liquor license - all while allowing authorities to secretly videotape and audiotape the transactions, according to the affidavit. Authorities have not accused Miller of any wrongdoing.

Graphic Development in Dianne Wilkerson's former Senate district

Miller, who works for the Boston firm McDermott, Quilty and Miller, was among the first lawyers Winn hired to work on Columbus Center. His firm is known for its success in advocating for clients within City Hall, where Winn was seeking permits and eventually taxpayer subsidies for his project.

Miller's work for Columbus Center was less about city zoning than it was about building relationships, according to executives and public officials involved in the debate over the project. He attended meetings in neighborhoods and private gatherings with city and state decision makers, helping to make a public case for the project. He also was involved in political fund-raising along with Winn, donating to Wilkerson and other public officials. Miller, who has donated $800 to Wilkerson since 2002, did not return phone calls seeking comment.

As Columbus Center moved forward in 2004 and 2005, Winn shifted his focus to obtaining public funding for the development, the price tag of which had grown to $500 million from $300 million because of rising construction costs. Winn was seeking taxpayer money to pay for a deck over the Massachusetts Turnpike to support the project. Typically, government officials approve public money for private ventures if they believe projects will spur more development or generate revenue for an area.

Up until then, Wilkerson had not regularly attended community meetings on the project, according to public officials who attended those meetings. But in the fall of 2005, she became one of its biggest supporters, vigorously advocating for public financing to get the project done.

State lawmakers opposed to public subsidies for Columbus Center took notice of Wilkerson's support in November 2005, when she advocated for a $4.3 million appropriation for the project in an economic stimulus bill in the state Legislature. In an interview with the Globe at the time, the senator called Columbus Center "my favorite project" and said the funding was for a "very small gap" in the financing.

The money was included in a Senate version of the bill, tripping alarms in the offices of opponents to public subsidies, including House Speaker Sal DiMasi.

"We had to scramble to kill it," said one legislative staffer, who is not authorized to speak publicly about such matters. "We weren't happy. We felt the developers had been pretty clear they were not going to seek public subsidies, and all of a sudden they were."

Winn and the development team, which included California-based MacFarlane Partners, said they never ruled out public financing.

Graphic Development in Dianne Wilkerson's former Senate district

Despite losing that fight, Wilkerson pressed on, taking her case to the city. The senator began supporting Winn's proposal to redraw Boston's empowerment zone, a 6.8-square-mile area that includes economically distressed areas from Dorchester and Jamaica Plain to the South Boston Waterfront. Inclusion in the zone would qualify Columbus Center for $32.5 million in tax-exempt loans and other tax credits.

The city's empowerment zone is administered by Boston Connects Inc., a private nonprofit organization responsible for initiating development and job-creation initiatives within its borders. Wilkerson is one of 30 public officials who serve as nonvoting members for the organization.

In April 2006, Winn's business partner, Roger Cassin, appeared before the board of Boston Connects to pitch a plan to include Columbus Center in the empowerment zone. Wilkerson, who attended the meeting, advocated for the proposal, telling board members that the development had been worked on for years and would produce significant benefits for city neighborhoods, according to minutes of the meeting.

Cassin told the Boston Connects board that Columbus Center would result in the creation of jobs for residents of distressed communities. He pledged to make best faith efforts to hire 60 percent of hotel employees from empowerment zone neighborhoods, which translates to about 150 jobs.

After his presentation, which included promised payments of more than $500,000 in fees and reimbursements to Boston Connects for its work to expand the empowerment zone, the organization's board voted to change the zone to include Columbus Center and other parcels over the Massachusetts Turnpike, essentially forming a narrow peninsula around the property. The move was also approved by HUD, but Winn never applied for the $32.5 million tax-exempt loan because of broader financial difficulties on the project.

Later in the year, Wilkerson stepped up her efforts even further, raising the issue of public subsidies with then-gubernatorial candidate Deval Patrick, according to his aides. In July 2007, after Patrick took office, he gave preliminary approval to $10 million in state grants for Columbus Center, triggering a public fight with DiMasi and other lawmakers who immediately began questioning why the governor included the money.

When their inquiries led to Wilkerson, she was unapologetic. "There are some folks who may take issue with this, but the fact is Columbus Center is probably our best and biggest chance for new job creation for the city of Boston," she told the Globe at the time.

The project was slated to produce a total of 2,600 construction jobs and 360 permanent positions, mainly connected to its 35-story hotel. Opponents of public subsidies sharply questioned the project's economic impact, arguing only a fraction would go to local residents. "The amount of money Senator Wilkerson wanted to give to Columbus Center is disproportionate to the 20 or 30 jobs she might get for her constituents," said urban planning activist Ned Flaherty, who lives in the neighborhood.

Patrick aides who attended private meetings with Wilkerson about Columbus Center grants said the administration supported the subsidies regardless of her stance, because of the project's potential to create jobs, spur additional development, and generate revenue for the Commonwealth.

By the fall of last year, as Winn and his partners prepared to break ground on Columbus Center, soaring construction costs had pushed the price tag to $800 million. As an economic slowdown set in, Winn failed to obtain a $430 million loan for construction.

Last April, the Patrick administration withdrew state funding for Columbus Center, and the project has remained at a standstill. In September, the development team hired new consultants to examine whether the project remains financially viable and to build support among key officials. The consultants, a team of Beal Cos. and Related Co., recently met with DiMasi to discuss their efforts, according to one official who participated in the meeting. The parties were introduced by Winn's attorney, Miller.

Wilkerson, meanwhile, will be replaced in January by Sonia Chang-Diaz, the newly elected senator for the district. Chang-Diaz said in an interview she does not support public subsidies for Columbus Center.

"I was never convinced that this project, which is so much about the hotel and luxury condos, is the right investment for the limited economic development dollars we have," she said. "You have to ask what else could be done with those dollars that may bring stable, long-term job growth for the neighborhoods.