Chicago's pedestrian mall solution: traffic

Fortunes soared with format shift

CHICAGO - State Street's problems 20 years ago will sound familiar to anyone who knows Downtown Crossing in Boston.

The historic downtown shopping destination, once anchored by classic department stores like Marshall Field and Goldblatt's, was dirty, dangerous, and down on its knees. The city had blocked off traffic on the street, turning it into a pedestrian mall in hopes of competing with suburban malls.

But instead of enlivening the street, the mall isolated it from the rest of downtown. Businesses closed, shoppers fled, pigeons and trash proliferated, and the street emptied into a wasteland at night. Like their counterparts in Boston, Chicago officials dispatched fruit vendors, hoping they would bring back shoppers. They didn't.

Under mounting pressure from business owners, the city made a fateful decision in 1996. Like hundreds of cities across the country, it decided to rip up its pedestrian mall and reconnect State Street to downtown.

These days, State Street is at the heart of a downtown renaissance. By day, diverse crowds of office workers, college students, and teenagers throng the sidewalks, passing hotels, coffee shops, bookstores, and clothing stores. By night, condo owners return to the upper floors of formerly decrepit department stores, students head to newly built classrooms and dorms, and visitors flock to rehabilitated theaters. Businesses power-wash the sidewalks and maintain planters. The local ABC affiliate even built a glass studio on State Street, turning the hubbub into a live backdrop, like Rockefeller Plaza on the "Today" show.

As Boston grapples with the decline of Downtown Crossing, the rebirth of Chicago's State Street is a case study of how a seemingly small change - opening up the area to traffic - can usher in a long period of growth and renewal. Chicago officials and business owners, like those in Boston, knew they ultimately needed more appealing stores, increased nighttime safety, and enhanced amenities for pedestrians. But unlike in Boston, they came to the decision that none of those changes would be possible if the city did not remove its pedestrian mall first.

"It was a very courageous decision because we had spent a lot of money to mall it, and we had to say, 'You know what? This is not working,' " said Christina Raguso, acting commissioner of the Department of Community Development. "Fortunately, the mayor could see past the mall, and see that there was still prosperity in State Street. And it's really a great story. It worked. It opened up so many economic opportunities and retail opportunities for the street, and made it a destination."

Like Downtown Crossing, which sees an estimated 230,000 people walk through every day, State Street always enjoyed heavy foot traffic. Even during its nadir in the 1980s, more than 20,000 people passed most corners of the nine-block mall every day, making it one of the most traveled areas in the city. But not until the street was reconnected to downtown did the district come back to life, city officials and planners say.

"It was just critical," said Philip Enquist, an urban designer at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which designed the removal of the mall. "I think State Street would not have succeeded had we not brought the cars back. The ripple effects have been phenomenal."

There are a few distinct differences between State Street and Downtown Crossing. The Chicago mall was larger than Boston's, nine blocks compared with four, and it was constructed on a wide thoroughfare that could handle four lanes of traffic and wide sidewalks to accommodate pedestrians, unlike Boston's narrower Washington Street.

Boston officials staunchly oppose the removal of the mall in Downtown Crossing, saying they hired consultants who concluded that it could still thrive. Some shop owners and developers agree, but as the district has suffered the closing of Filene's and Jordan Marsh in recent years, others argue that it is time for the mall to go.

"It just has created this blockage," said John B. Hynes III, the developer and grandson of Boston Mayor John B. Hynes, who is struggling to finance the conversion of the former Filene's building into a residential and retail tower. "I've talked to a dozen retailers, and they wish that people could drive through, just because it makes it easier to drop people off and pick them up."

American cities built more than 200 pedestrian malls in the 1960s and 1970s, when they were losing shoppers to proliferating suburban malls and hoping to draw them back with placid, car-free walkways in their downtowns. Chicago built its mall in 1979; Boston built its in 1978.

"In those days, the suburbs were hot, white flight was taking place, and people were scared of urban America," said Ty Tabing, executive director of the Chicago Loop Alliance, the downtown business association. "It was a different era then, when these things made sense."

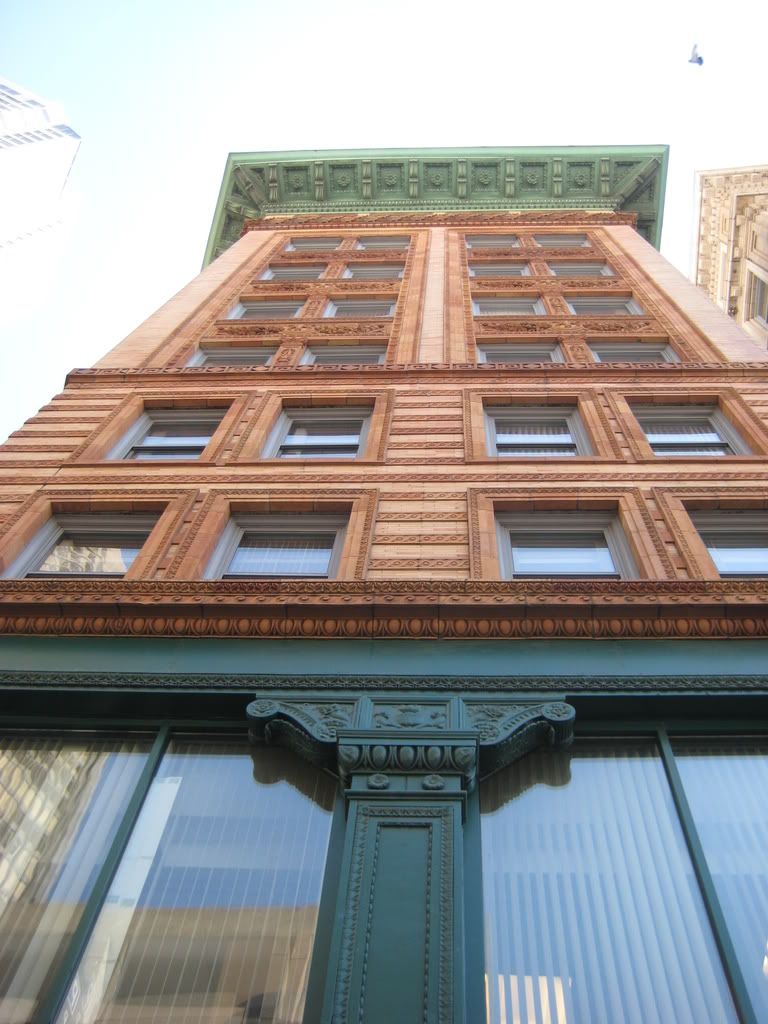

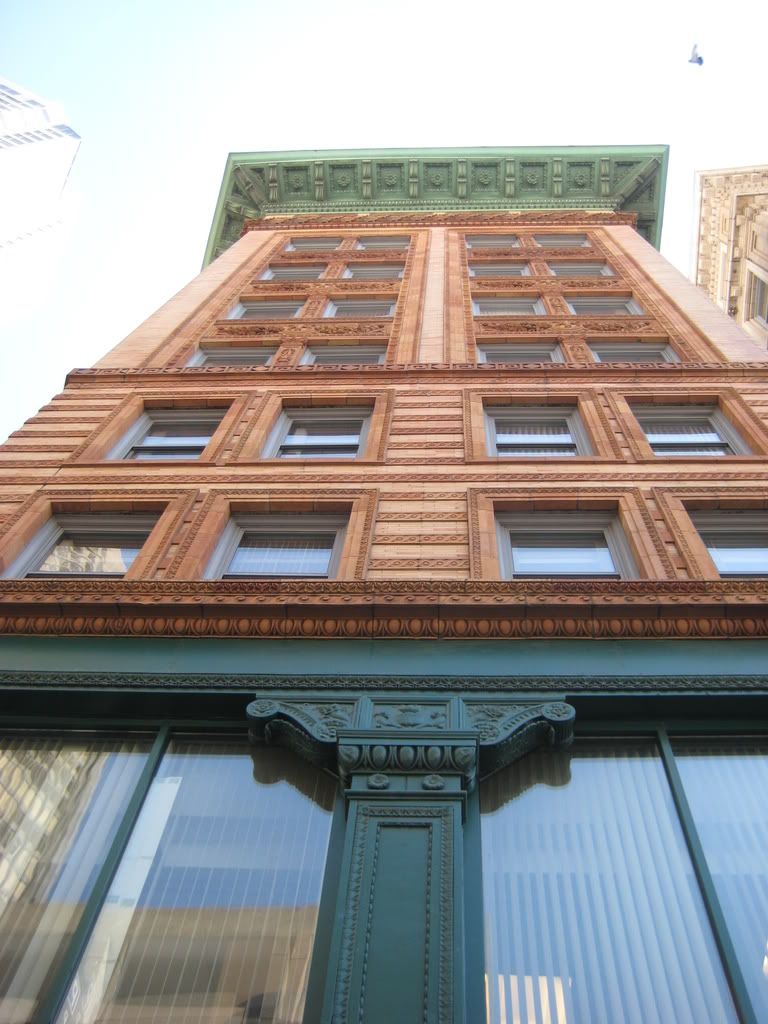

In Chicago, city officials and shoppers soon came to regard the State Street mall as a failure, pocked with fast-food outlets, wig shops, and discount stores. The Reliance Building, a grand skyscraper from the 1890s, became a symbol of its decline, a vacant "flophouse for pigeons," in the words of one city official.

"This group of businesses were extremely frustrated with the mall," Enquist said. "It was downbeat. The businesses were really failing. It was very inactive at night. Hotels wouldn't even have State Street on the map because they didn't want people walking there at night. It only had police cars and buses so it had this terrible feel to it."

In early 1996, the city scrapped the mall. These days, only about two dozen downtown malls remain nationwide, as officials and planners came to a reluctant conclusion: that the lack of traffic hurt downtowns by walling them off from the rest of the city.

"The lesson is that cities are about activity and energy," said Elizabeth Hollander, who was Chicago's planning commissioner in the 1980s and is now a senior fellow at Tufts University. "What they want to do is make themselves different from suburban malls - that's their niche."

In the last decade, State Street has seen an influx of business. The Reliance Building was rehabilitated into a boutique hotel, the Burnham. A mix of stores - Old Navy, Urban Outfitters, Land's End, Macy's - have opened, and the refurbished Chicago Theatre, Gene Siskel Film Center, and Joffrey Ballet draw nighttime visitors. The area still has its problems - several vacant buildings, rowdy loiterers.

But the outlook is much brighter than it was in the 1980s.

"It went into a downward spiral," said Ronald M. Arnold, vice president of business affairs at Robert Morris College, which is located on State Street. "When the street was reopened, life came back to it. It's just that activity and bustle that creates that excitement, that feeling of safety and security that makes things happen."

Michael Levenson can be reached at

mlevenson@globe.com.