This is an article from "landscape architecture" 8/07

I couldn't find it on the we-site, so I typed the whole thing in...don't ask me why.

In the Perspective section of Landscape Architecture

ACCIDENTAL PARKS

Cities are creating open space from urban remnants.

But can remnants effectively bind the city together?

By Peter Gisolfi, ALSA

Cities are more and more often developing new parks from leftover bits of land. Granted, these cities are almost completely developed, so there is little land left over for parks. Nevertheless, the current park model is very different from the grand urban visions of the past, when land for parks was deliberately set aside in the city plan.

The earliest city plans, which are still celebrated, placed the main open space at the center. Examples are the cities of Boston and New Haven Connecticut, where the town surrounds a green or a common. More elaborate plans include the systematic integration of multiple greens withing gridded plans, such as those found in Philadelphia and Savannah Georgia. In the second half of the 19th century, the parks movement embraced a grander vision. Central Park in Manhattan, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and the Boston Park system were created with ambitious social and environmental objectives in mind. The reformers believed intensely that bringing the pastoral beauty of the countryside to growing cities would remedy the social ills brought by the Industrial Revolution and teeming immigrant populations.

After the World?s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the city beautiful movement focused on transforming existing cities in a manner similar to Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann?s interventions in Paris. From that movement came the great boulevards we continue to recognize today-Mosholu Parkway in the Bronx, Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn, Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. The purpose of these boulevards was not only to bring green space to the city core, but also to transform the city plan by creating new processional connections.

After World War II, the greatest urban open space intervention in America unwittingly turned out to be the Interstate Highway System. No matter what we think about the urban renewal efforts of that era, the construction of interstate highways through and around major cities was one of the most significant events. Picture Hartford, Connecticut, split by I-84; New Haven, Connecticut, cut off from Long Island Sound by I-95; I-90 intersecting Commonwealth Avenue in Boston; or I-5 on two levels at the edge of Puget Sound in Seattle. These were the great open-space initiatives of the 1950s and 1960s, even if they did not produce green space. Swaths of asphalt cut through the existing urban fabric to create the largest continuous open-space systems in the history of American cities.

What are we doing now to create open space? By necessity, we are focusing on remnants from previously used land within the city. But does this method of selecting open space bind the city together?

New Parks on Remnants

Three projects are prime examples of the way parks are being sited today. They all are major, long-term commitments to open space development, and they are similar in that they are all being built on transportation remnants from a previous age.

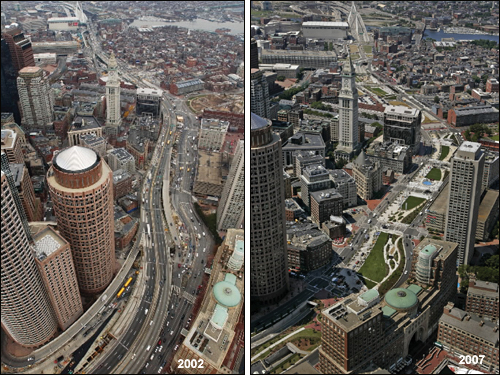

In the center of Downtown Boston, the central Artery/Tunnel Project, familiarly known as the Big Dig, replaced an elevated high-way with an underground expressway directly beneath the preexisting road. This created many acres of open land for the creation of future parks and public plazas. Of the 27 downtown acres on the footprint of the old elevated highway, 75 percent are reserved for open space. At issue is not the tearing down of the elevated highway. That undertaking is splendid. The concern is how to treat the remnant. At present, the footprint of the old Central artery remains clearly visible in the urban landscape of downtown Boston. It has become a wide, winding boulevard with a central green mall, which in theory would benefit the city?s residents. However, the space is out of scale with the adjacent streets and buildings.

Similarly questionable is the High Line, constructed in the 1930?s as an elevated railroad line through the Lower West Side of Manhattan. The railroad was abandoned more that a quarter century ago, but the steel structure supporting it, although deteriorating, is still standing. Friends of the High Line, a private organization, lobbied against removing the elevated structure. New York City purchased the site, and a design competition, hosted by the Friends group, produced a plan for a greenway, similar to the Promenade Plantee in Paris. The city has promised to invest $50 million to restore a one-and ?a-half mile section of the line and turn it into an elevated urban park. Construction began in spring 2006. As first steps, workers are shoring up the old rusting structure and tearing out the rails. The city has decided to build a park above street level, to ber supported forever by a steel structure more than 70 years old.

A third park, the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary, is located on a 27-acre site near the Mississippi River, near downtown St. Paul, Minnesota. In the 1850s, settlers established a brewery on the site, and later, a portion was converted to a train yard. The original natural landscape was destroyed to create a place for transportation (the railroad) and industry (the brewery). This type of construction is typical of 19th ?and 20th-century urbanization. Both enterprises had been abandoned by the 1970s, and the area became an illegal dumping ground.

Transforming the polluted, industrial remnant was a 10-year effort initiated by community members organized as the Lower Phalen Creek Project. It involved the City of St. Paul, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the National Park Service, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and about 25 civic and environmental groups, including the Dakota Indians. The actual construction took about three years.

The park is an elongated landscape defined on the south by the railroad, which rune parallel to the Mississippi and separates the park form the river. The park design is primarily and ecological restoration of the site. A groundwater-fed stream and three wetlands that total two and a half acres were reconstructed, and 1.4 miles of local and regional trails were built. The site also includes rare swamps and four acres of bluff prairie. Similar to Gas Works Park in Seattle, which preserves remnants that memorialize its industrial past, the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary has retained remnants of its rail and brewing operations. Although the park was open to visitors in 2005, work continues. The new bicycle path, which will connect to a web of city and suburban trails, is scheduled to open this summer.

The configuration and edge conditions of the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary illustrate the dilemma faced in creating parks from remnants. These parks often will be works in progress as we wrestle with the question of how much of our riverfronts must be dedicated to transportation systems. In this particular case, the park does not extend to the edge of the Mississippi, although a proposed pedestrian bridge over the street and railroad will provide a tenuous connection to the river.

Observations

In looking at these three remnants, I am struck by the fact that all three are linear elements. One, a railroad yard at grade along the Mississippi; the second, the footprint of an elevated highway cutting through Boston; and the third, and elevated railroad parallel to the Hudson River in lower Manhattan. Once the transportation or industrial remnant no longer serves its original purpose and is to be demolished or transformed, does the city plan necessarily require a linear open space? This question raises important issues:

Location Is there something inherent in a particular city plan that suggests a rational location for new open space-or is the only criterion that a particular remnant is available? The St. Paul example, adjacent to the Mississippi waterfront, seems to be a natural place for a public park, even though it is cut off from the river. The argument in favor of a park in this location is made more compelling by the fact that a stream and wetlands were previously destroyed and now have been restored. In the idealized view of how cities might develop, we hope that the natural infrastructure of streams, wetlands, and steep slopes-those places that are inhospitable to urbanization-will be preserved in their natural stats. The locations for the other two examples-the Big Dig and the High Line-are more debatable. Perhaps the High Line is superfluous or would have been better located at grade. The Central Artery footprint at the Big Dig might better be used for smaller segments of open space.

Connections The original town plans that were integrated with open space used open space as connectors. Boulevards and parkways were designed to be links in a system of urban open space. The Benjamin Franklin Parkway, for example, connects two of the original five squares in Philadelphia to the city?s art museum and to Fairmont Park beyond. None of the three parks discussed make such connections. The alignment of the Central Artery portion of the Big Dig does not create major urban connections along it?s length, although it does allow for connections that are perpendicular to that alignment. The High Line does not connect any larger elements of the city fabric. Eventually, the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary might become part of a connected system, but it is compromised by the remaining railroad and roadway, which define a significant portion of its perimeter.

The Place of the Natural Landscape in the City When American cities were first constructed, much of what was naturally there was destroyed. Streams became storm sewers, and waterfronts became industrial sites, railroads, and highways. Only rarely were natural features preserved. (A notable exception is the city of Boston, where Frederick Law Olmsted worked with natural features and processional elements to create a linear, interconnected urban park system that complemented the overall plan of the city.) In Manhattan, the escarpments of Morningside Park and St. Nicholas Park survived simply because they were too steep to serve as construction sites. But do the original natural features, such as stream-beds, floodplains, and steep slopes, still provide clues to where open space might best be located? Do the remnants discussed here correspond in any way to that idea or to the idea of celebrating and connecting important natural features? Certainly the Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary restores a natural landscape and is parallel to the most important natural feature in St. Paul-the Mississippi River. It can be argued that the views from the High Line to the Hudson will be spectacular, even though nothing natural is being preserved or restored. The Central Artery portion of the Big Dig can make no claim to restoring, celebrating, or connecting natural features.

Granted, it is extremely difficult to implement major urban projects, but can we be visionary? Can we design significant open space systems in American cities? Or will we continue to create open space randomly as a result of the efforts of individual groups that lobby to transform specific remnants? The most important urban connections to be made in Boston are perpendicular to the alignment of the demolished highway, making the memorialization of the highway right-of-way seem arbitrary. In the case of the High Line, I think we are being driven by transportation-remnant nostalgia and economic opportunity for property owners immediately adjacent to the elevated railroad line. Perhaps the public open space of the city belongs at grade-a topic that was debated extensively in the 1960s and 1970s. All of this brings to mind the point made earlier that linear connections should either preserve or restore the natural infrastructure or make important connections within the overall city open space plan.

Future open space in existing cities will be idiosyncratic, derived predominantly from industrial and transportation remnants. Even though new open space created from remnants seems haphazard, I believe we can choose to build it in a way that supports or reinforces the overall city plan. In Boston, Olmsted created episodic parks and open spaces, keeping in mind that smaller projects to come always would be part of the grand plan.

I ask our planners, landscape architects, politicians, and advocacy groups to be modern-day Olmsteds-to be visionaries who can plan episodic open space without losing sight of its potential within the larger system. Be stewards of the big picture. Keep in mind the plan of the city, the overall configuration of open space, the potential of new open space to create connections within the urban fabric, the value of a system that serves human needs, and the importance of restoring and linking to the underlying natural landscape