Re: South Boston Seaport

Home /Globe /Opinion /Op-ed Joan Vennochi

McCourt and the mayor

By Joan Vennochi

FRANK MCCOURT owns his West Coast failure.

Tweet 1 person Tweeted this.ShareThis .His Boston failure he shares with Mayor Thomas Menino.

McCourt was the architect of his own demise in Los Angeles when he sold 24 acres of seaport parking lots in Boston in order to buy the LA Dodgers. It was a terrible trade. Today, a sparkly new $3 billion neighborhood of condos, offices, shops, and hotels is supposedly on the brink of rising from those scabby, old parking lots. Meanwhile, the Dodgers franchise is in bankruptcy.

McCourt leaves the Dodgers more than $525 million in debt, while the commissioner of baseball also accuses him of diverting more than $180 million in team assets to finance a lavish L.A. lifestyle. McCourt’s messy split with his wife and longtime business partner, Jamie McCourt, ended in one of the most expensive divorces in California history.

What happened with the Dodgers is McCourt’s fault. But what happened first in Boston explains why the Seaport District is still a hodgepodge, although a livelier one than it used to be. McCourt once had dreams for those parking lots, but they went nowhere.

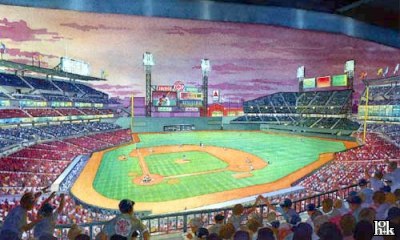

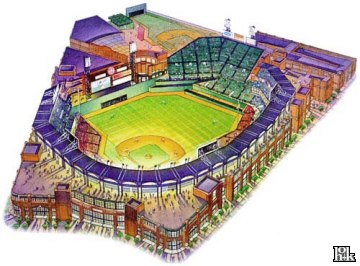

News stories from the 1990s describe McCourt as a hard-nosed visionary. He was also volatile, impatient, and brash. For years, he carted a slideshow around town, offering journalists and business groups detailed renderings of a graceful, new Back Bay on the waterfront. His proposals for the seaport ran the gamut from office towers to luxury hotels, shops, and condos. He also bid unsuccessfully for the Boston Red Sox, and wanted to build a new ballpark on his land.

Menino disliked McCourt and had little faith in his assorted visions. The mayor was also responding to pressure from assorted interest groups, including South Boston residents, who worried about building heights and an influx of outsiders. From all that came the now-classic Menino refusal to do business with someone outside his inner circle.

Given McCourt’s West Coast flop, Menino’s resistance may look prophetic. But years later, doesn’t it also look a little short-sighted? Seaport development could not move forward without that critical mass of McCourt-owned acreage. Thwarting McCourt also thwarted economic development, and all the tax revenue that would flow from it.

The parking lots that McCourt used as collateral for his loan to buy the Dodgers were eventually sold to Morgan Stanley and Boston developer John B. Hynes III. It took 15 years for another developer to do what McCourt could not do - sell a creative seaport development proposal to the city. Hynes has also had problems with Menino, especially after his involvement in the failed Filene’s department store block at Downtown Crossing.

The hole in the ground that Hynes opened but never closed evolved into one of Menino’s biggest development headaches. Yet the city still worked with Hynes on his Seaport plans. Eventually, he came up with a proposal that conformed to Menino’s wishes.

When Hynes first proposed plans for the waterfront in 2006, Menino’s reaction was reported as lukewarm. In 2010, when zoning for Seaport Square was finally approved, the Hynes plan was close enough to the Menino plan to yield this hard-won mayoral blessing: “Seaport Square has embraced the challenge of the innovation district: to be bold, creative, and keep our economy growing.’’

Some people said the same thing about the plans McCourt offered up so many years ago. But personality got in the way of progress, as it so often does in Boston.

The mayor long ago crowned himself the city’s chief architect and urban planner. Now in his fifth term, he presides over a development process that is slow, cumbersome, and tilted toward a small group of favored insiders who do what he wants.

Menino has done many good things. But when it comes to development, they will always be measured against what the city might have accomplished years earlier if he were more open to people and ideas that fall outside his comfort zone.

McCourt fell outside Menino’s comfort zone and from there, he fell flat on his face.

His sad Hollywood ending was first a sad Boston story. That plot had consequences not only for one foiled developer, but for an entire city.

Joan Vennochi can be reached at

vennochi@globe.com.

http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/oped/articles/2011/08/07/mccourt_and_the_mayor/