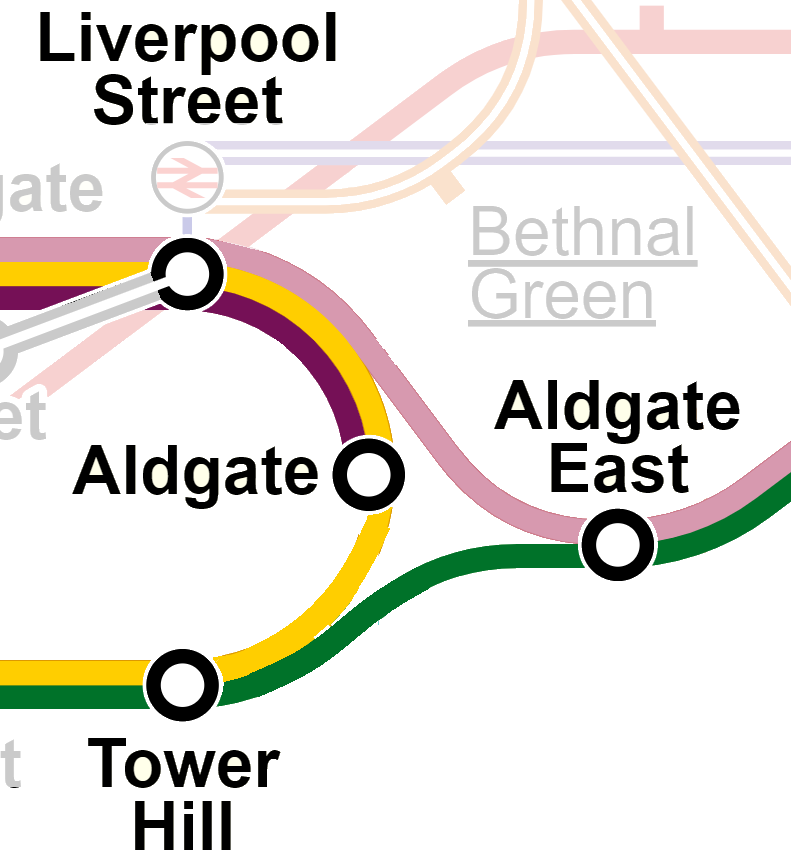

Today’s post gives a name to a kind of transit system topology that is somewhat common but doesn’t have a specific name. I have coined it the “Aldgate Junction”, named after the junctions at Aldgate on the London Underground:

Aldgate Junctions both complicate and simplify. On the one hand, they enable a larger variety of one-seat rides and increased frequencies on branchlines. On the other hand, they entangle all affected branches into one big complex service, which can impact reliability and sometimes can ultimately put a cap on overall capacity.

We’ve talked a lot about Aldgate Junctions over in the Green Line Reconfiguration thread (where I’ve put some additional comments specific to those proposals). Boston doesn’t have too many other Aldgate Junctions (although we once did – stay tuned for another post on that). Beyond the possibilities on an expanded Green Line network, probably the two best-known examples are both on the commuter rail network.

On the southside, we have the South Cove Loop, which connects the NEC and the Fairmount/Old Colony Tracks. Every so often, someone suggests using this to run trains from Fairmount or Old Colony to Back Bay and Allston or Newton. This is a case where insufficient infrastructure exists to make a functional Aldgate Junction: the loop track only connects to the southernmost track of the NEC, requiring trains for Allston/Newton to cross almost every single other track before reaching Back Bay, which would block off multiple tracks and impede the much higher priority traffic between Back Bay and South Station.

On the northside, we have trackage near the erstwhile Boston Engine Terminal, which connects the Fitchburg Line to the B&M routes at Sullivan Square. (Technically, these tracks were part of the original Grand Junction Railroad, though nowadays we often use that name to refer solely to the segment between the Fitchburg Line and the B&A Line in Allston.) These tracks would enable trains to run from the Fitchburg Branch to either the Reading Line or the Eastern Route without hitting North Station. In some far hypothetical future, I could possibly imagine a Waltham-Lynn RER service leveraging these tracks, but for the foreseeable future, this seems unlikely, as slots on the Eastern Route will need to be devoted to the much more valuable North Station destination.

From a mapping perspective, Aldgate Junctions pose interesting challenges. Today’s Tube map (as shown above) uses three different colors for each “leg” of service across the junction: yellow for the Circle, pink for H&C, green for the District. But different strategies have been adopted in the past. (All examples below drawn from https://www.clarksbury.com/cdl/maps.html)

In 1933, the Tube used purple for both the northern legs, and maintained green for the southern leg, and showed the purple just sorta mysteriously merging into the green lines. This reflected the heritage of the services as separate railroads that shared each other’s tracks.

The New York City Subway also uses a similar “2+1” solution for most of its Aldgate Junctions, where two legs are conceptualized as “branches” of a single core service, and a separate line identity is used for the bypass.

Keen observers will note that just to the east of the Aldgate Junction, another line appears to branch off of the green District Line, leading to the East London Line. The ELL was at various points considered part of the Metropolitan Line, and was at various points colored accordingly, such as in 1958 (even though direct services were not running between the ELL and the rest of the Met at that point):

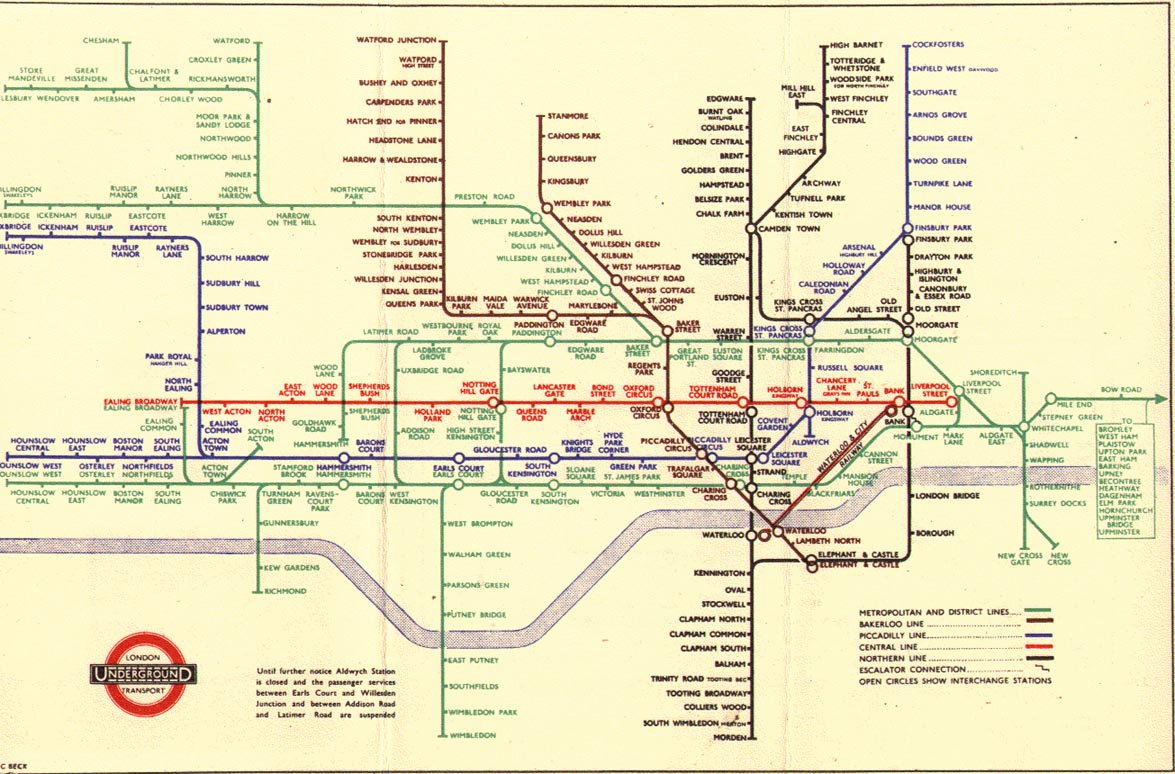

But in earlier years, when direct service was run from Algdate East on to the East London Line, the division between “purple” Metropolitan services and “green” District services was not so clean. And so it’s unsurprising that 1940s Tube mapmakers just threw their hands in the air, and colored the whole thing – Metropolitan and District lines – a single green, stretching from Aylesbury to Upminster and encompassing… 15 (?) branches! See for example this map from 1945:

The “one color” approach seems less-than-ideal to me – you’re basically telling riders, “Yeah this is complicated, you will need to do more research before traveling.”

(This map has one more Aldgate Junction hidden in there – bonus points if you can find it!)

An Aldgate Junction is essentially a wye junction that is robust enough to handle full revenue service on each leg. While this may suggest that the term is redundant, I argue it’s worth distinguishing: wyes are often used for non-revenue service and often are built accordingly. The South Cove Loop is a good example: it’s useful for limited train moves as needed, but it can’t be scaled up. Moreover, historically in North America wye junctions are much more commonly used for turning equipment – indeed, most of the examples listed in the linked article are for that purpose.

These really are very different, therefore, in both use and character from something like the Oakland Wye, which is an enormous three-way flying junction that sees nearly every BART train passing through – something like 40 trains per hour across all branches in all directions. (That’s a train every 90 seconds!) So, I argue, it’s worth having a distinct name for this distinct kind of service and infrastructure.

Aldgate Junctions both complicate and simplify. On the one hand, they enable a larger variety of one-seat rides and increased frequencies on branchlines. On the other hand, they entangle all affected branches into one big complex service, which can impact reliability and sometimes can ultimately put a cap on overall capacity.

We’ve talked a lot about Aldgate Junctions over in the Green Line Reconfiguration thread (where I’ve put some additional comments specific to those proposals). Boston doesn’t have too many other Aldgate Junctions (although we once did – stay tuned for another post on that). Beyond the possibilities on an expanded Green Line network, probably the two best-known examples are both on the commuter rail network.

On the southside, we have the South Cove Loop, which connects the NEC and the Fairmount/Old Colony Tracks. Every so often, someone suggests using this to run trains from Fairmount or Old Colony to Back Bay and Allston or Newton. This is a case where insufficient infrastructure exists to make a functional Aldgate Junction: the loop track only connects to the southernmost track of the NEC, requiring trains for Allston/Newton to cross almost every single other track before reaching Back Bay, which would block off multiple tracks and impede the much higher priority traffic between Back Bay and South Station.

On the northside, we have trackage near the erstwhile Boston Engine Terminal, which connects the Fitchburg Line to the B&M routes at Sullivan Square. (Technically, these tracks were part of the original Grand Junction Railroad, though nowadays we often use that name to refer solely to the segment between the Fitchburg Line and the B&A Line in Allston.) These tracks would enable trains to run from the Fitchburg Branch to either the Reading Line or the Eastern Route without hitting North Station. In some far hypothetical future, I could possibly imagine a Waltham-Lynn RER service leveraging these tracks, but for the foreseeable future, this seems unlikely, as slots on the Eastern Route will need to be devoted to the much more valuable North Station destination.

From a mapping perspective, Aldgate Junctions pose interesting challenges. Today’s Tube map (as shown above) uses three different colors for each “leg” of service across the junction: yellow for the Circle, pink for H&C, green for the District. But different strategies have been adopted in the past. (All examples below drawn from https://www.clarksbury.com/cdl/maps.html)

In 1933, the Tube used purple for both the northern legs, and maintained green for the southern leg, and showed the purple just sorta mysteriously merging into the green lines. This reflected the heritage of the services as separate railroads that shared each other’s tracks.

The New York City Subway also uses a similar “2+1” solution for most of its Aldgate Junctions, where two legs are conceptualized as “branches” of a single core service, and a separate line identity is used for the bypass.

Keen observers will note that just to the east of the Aldgate Junction, another line appears to branch off of the green District Line, leading to the East London Line. The ELL was at various points considered part of the Metropolitan Line, and was at various points colored accordingly, such as in 1958 (even though direct services were not running between the ELL and the rest of the Met at that point):

But in earlier years, when direct service was run from Algdate East on to the East London Line, the division between “purple” Metropolitan services and “green” District services was not so clean. And so it’s unsurprising that 1940s Tube mapmakers just threw their hands in the air, and colored the whole thing – Metropolitan and District lines – a single green, stretching from Aylesbury to Upminster and encompassing… 15 (?) branches! See for example this map from 1945:

The “one color” approach seems less-than-ideal to me – you’re basically telling riders, “Yeah this is complicated, you will need to do more research before traveling.”

(This map has one more Aldgate Junction hidden in there – bonus points if you can find it!)

An Aldgate Junction is essentially a wye junction that is robust enough to handle full revenue service on each leg. While this may suggest that the term is redundant, I argue it’s worth distinguishing: wyes are often used for non-revenue service and often are built accordingly. The South Cove Loop is a good example: it’s useful for limited train moves as needed, but it can’t be scaled up. Moreover, historically in North America wye junctions are much more commonly used for turning equipment – indeed, most of the examples listed in the linked article are for that purpose.

These really are very different, therefore, in both use and character from something like the Oakland Wye, which is an enormous three-way flying junction that sees nearly every BART train passing through – something like 40 trains per hour across all branches in all directions. (That’s a train every 90 seconds!) So, I argue, it’s worth having a distinct name for this distinct kind of service and infrastructure.