MBTA Experiment Gone Wrong! The Green Line Extension Contract

September 15, 2015

Written by Lauren Corvese

The Green Line Extension (GLX) is a long-awaited MBTA project, the result of a lawsuit settlement involving Big Dig mitigation and the Federal Clean Air Act. The project as planned will add two branch lines to the northern end of the green line with five miles of new track, seven new stations, a vehicle storage maintenance facility, and an extension of the Somerville Community Path. Recently, an estimated $1 billion cost overrun was announced, on top of the nearly $2 billion original price tag.

The project is now 50 percent over budget—the budget that was used to secure 50 percent funding by the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). Because the 50 percent federal funding was locked in at the original (and clearly underestimated) value of just under $2 billion, the overrun falls to the backs of Massachusetts taxpayers.

The billion dollar question: How could the MBTA have been blindsided by the Big Dig-esque price hike?

One of the answers (and the Globe agrees) is the experimental use of a new procurement method, Construction Manager/General Contractor (CM/GC), and how it essentially blew up the lab.

CM/GC was approved by the legislature in 2012 as an innovative procurement method with the notion that it would streamline the design and construction process and actually lower costs. With CM/GC, the MBTA conducted two basic phases of procurement: first, it issued a Request for Qualifications (RFQ) to determine which firms were most qualified to work on the project. Second, the MBTA directed the “qualified” proposers to submit Technical and Price Proposals. The MBTA then reviewed and evaluated the proposals, awarding the contract to the “best-value” bidder, based 60 percent on the technical and 40 percent on the price components. The catch is that the price component does not actually set a price; rather, the Price Proposal sets a CM/GC Multiplier— a fixed percentage of home office overhead and profit to be included in each Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP). Thus, the price component of the bid does not establish the total cost to the MBTA, nor does it provide a means to control costs. Rather, it sets a percentage limit for how much the CM/GC can charge for overhead costs and profit. Under the CM/GC procurement method, the contractor’s profit rises in direct proportion to project cost, creating little incentive for the contractor to limit total project cost. In short, the CM/GC—White Skanska Kiewit— won the bid without submitting a price estimate, which is generally the basis of a rigorous bidding process.

CM/GC versus other procurement methods

Comparing CM/GC to other procurement methods best illustrates the enormous drawback of CM/GC with regard to price competition and financial risk.

CM/GC is drastically different than the state’s typical procurement method and also vastly different than Design-Build, a method used on a light-rail project in Los Angeles that will be revisited later. In Massachusetts, most public construction projects use Filed Sub-bid or an improved version called Construction Manager (CM) at Risk. CM at Risk involves the agency first hiring a designer to create a full design plan. Then, the agency sends the design out for bid, only to “prequalified” CM firms (3 minimum). The lowest prequalified bidder is awarded the CM contract. At this point, the agency, with input from the CM and the Designer, reviews potential sub-bidders and the award goes to the lowest “prequalified” sub-bidder. Although there are disadvantages to this method, such as the CM having to work with sub-bidders it has no prior experience with, one thing is clear: the cost is known upfront.

Design-Build is another procurement method that is gaining popularity and has been recently used on a transit project in LA. With Design-Build, the agency writes up general specifications for a project, using either in-house designers or hiring an independent firm. Then, the agency sends the bid out to numerous firms that must create a joint venture between a Designer and General Contractor to create and submit final architectural plans for the project, along with construction plans and a guaranteed maximum price (GMP). At this point, the agency uses a “best value” selection process, selecting the Design-Build entity based on a comparison of the design that best fits the agency’s needs to the price it is offered at. Thus, the agency does not have to limit itself to the cheapest option, as another, relatively more expensive design may better suit the agency’s needs. An advantage to this method is that by granting more creative freedom to the Design-Build bidders, the agency can assess “best value” based on both design and cost.

CM/GC takes a vastly different approach. The process for hiring the designer and the CM/GC occurs simultaneously, but involves separate firms (unlike Design-Build). The agency hires an independent designer based solely on qualifications. Likewise, the agency first narrows down firms that will be considered for the CM/GC contract on the basis of qualifications, not price. The agency sends these qualified firms procurement bid documents that set forth initial design and construction plans. Then, the CM/GC submits its bid and is chosen based on its technical and price (CM/GC Multiplier) proposals. Once chosen, the CM/GC is expected to work with the designer and give input on design and constructability before the design is finalized. Thus, the CM/GC is awarded before any price estimates are submitted. In an effort to safeguard the agency against outrageous costs, CM/GC also includes an Independent Cost Estimator (ICE) that is hired to review and verify each GMP, as the project is split into phases and subdivided into smaller contracts to streamline the process. Even with an ICE, this is a risky method because the cost of the project may be estimated upfront, but is not locked in at a Guaranteed Maximum Price before the contract is awarded.

Warning signs ignored

The first and most obvious issue with the use of the CM/GC procurement method for the Green Line Extension is that a guaranteed price was not included as a component of the bidding process. White Skanska Kiewit (WSK) was awarded the CM/GC contract before the design had been completed. This eliminated any form of meaningful price competition from the procurement process, resulting in the cost overrun catastrophe the MBTA faces today. Furthermore, this method incentivized WSK to overstate project costs, both in order to protect themselves from the risk of exceeding the GMP and to maximize its overhead and profit that is included in its CM/GC Multiplier. With the CM/GC procurement method, WSK was under no pressure to submit competitive prices, due to the absence of competition. Instead of using a procurement method where the price, or at least the GMP, is known in advance, the MBTA used a method where prices are negotiated between the agency and the CM/GC for each smaller construction contract during the project. The MBTA took a financial risk by using this method, and ultimately their plan to save money and streamline the project backfired.

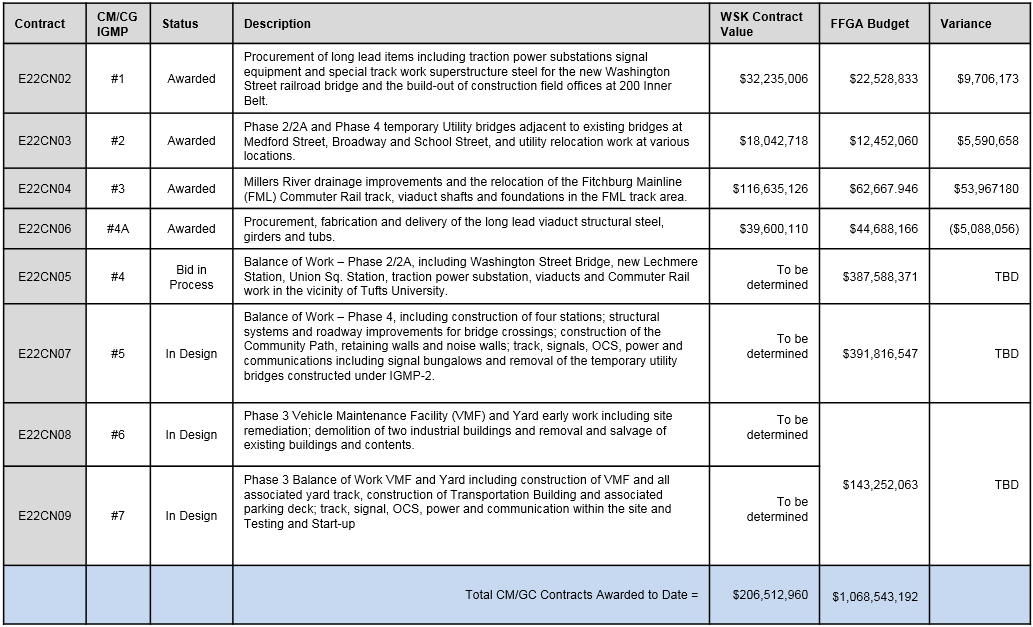

The only financial safeguard in place was the ICE, but even this precaution did not prevent a cost overrun of $1 billion. This prompts the question, did the ICE do its job? The ICE was supposed to verify WSK’s estimates as reasonable before the MBTA awarded each contract at their respective GMPs. So did it? Well, since the MBTA has made payments to Stanton Constructability Services—the firm awarded the ICE contract— one would assume so. But when WSK’s cost estimates came in for GMPs #1-3 at 43 percent, 45 percent, and 86 percent over budget, respectively, why were these contracts awarded? Perhaps these estimates actually were verified by the ICE because they reflected changes in the final design and/or current price of materials and labor. But even if so, the MBTA should have been concerned from WSK’s very first GMP contract estimate, not just the most recent one—the fifth. GMPs 1-4A were awarded despite a cost variance of over $60 million. Wouldn’t that be a red flag?

MBTA GLX slide from presentation

(From MassDOT August 24 FMGB Meeting PowerPoint Presentation)

What could have been: Design-Build procurement method used in LA

The LA Metropolitan Transportation Authority (LA MTA) Expo Light Rail project provides a great comparison to the Green Line Extension. The LA project was split into two phases. Phase 1— laying 8.6 miles of track from downtown LA to Culver City— was something of a nightmare for the LA MTA. It experienced numerous cost overruns from a bid of $420 million and a budget of $640 million to a final cost of $930 million.

After experiencing these cost issues, Phase 2 of the project was procured using Design-Build. The project was bid at $1.5 billion with the price inclusive of design costs, construction, utility relocation, light rail vehicles and real estate. Phase 2 involves a 6.6-mile extension between Culver City and Santa Monica, including seven new stations, seven major bridges, and three park-and-ride lots. In comparison, the GLX project includes 5 miles of new track, seven new stations, a vehicle storage maintenance facility and a bike path extension. The GLX is comparative to the LA MTA Expo Light Rail project, but is coming in at nearly double the price tag. Why?

If the MBTA had used Design-Build, there’s a chance we would not be looking at a $1 billion overrun. The irony is that the MBTA could have used this method; Design-Build is one of the alternative delivery methods approved for use in MA c. 193 of the Acts of 2004 and was even under consideration for the Green Line Extension. Since Design-Build combines the benefits of CM at Risk and CM/GC by requiring the designers and builders to collaborate and requiring a GMP before awarding the contract, we wonder why it wasn’t the MBTA’s choice for the GLX project.

Conclusion

Using the new procurement method for the Green Line Extension—CM/GC— has left the MBTA and therefore Massachusetts taxpayers on the hook for nearly $1 billion in unanticipated costs and counting if the project moves forward. CM/GC’s focus on hiring the most qualified contractor excluded one of the most important aspects of the procurement process: price. Utilizing a method such as Design-Build that incorporates GMP as well as qualifications would seem to have been a better approach.

The MBTA should have recognized the ballooning cost issue long before WSK’s latest estimate. GMPs #1-3 should have been warning signs that the project was in danger of going far over budget. Under CM/GC, the MBTA could have re-bid at any time and it probably should have much sooner. The agency can still rebid now; the problem is that the MBTA is backed into a corner because of time. But one of the only ways the GLX project can potentially be salvaged is by rebidding the project and utilizing true price-based competition.

Lauren Corvese is a student at Northeastern University working as a Research and Programs Assistant at Pioneer Institute through the Co-op Program.

http://pioneerinstitute.org/news/mbta-experiment-gone-wrong-the-green-line-extension-contract/