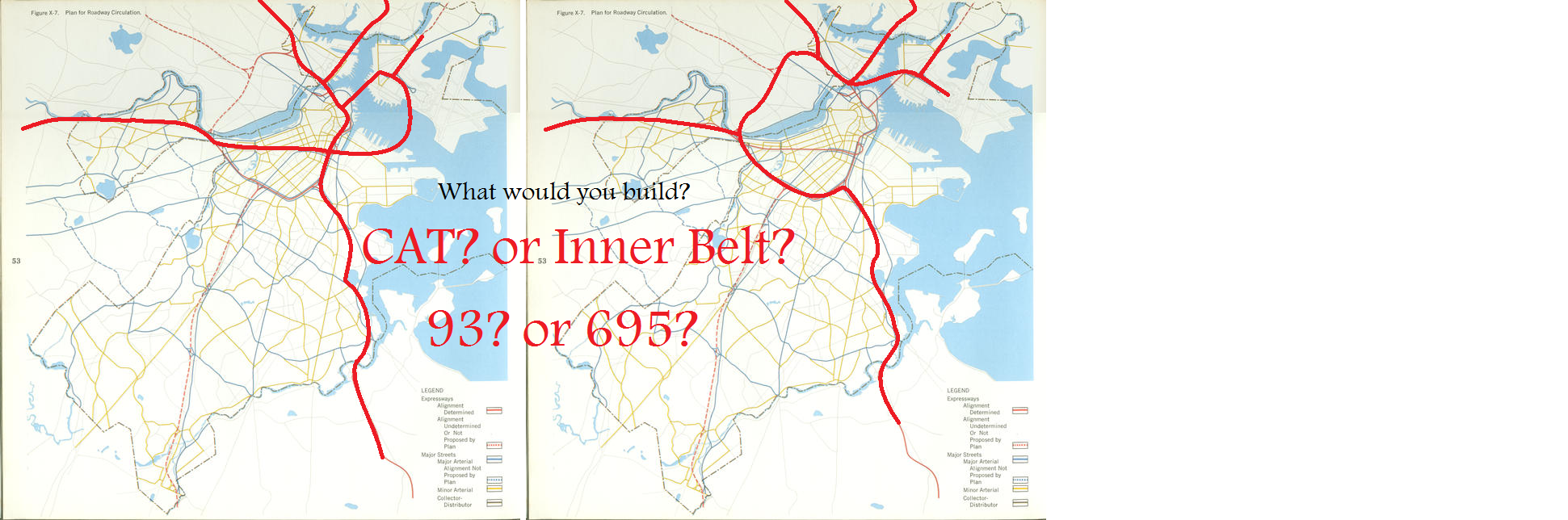

Are we deciding on whether we would have built CAT or the Inner Belt, with the 93 having already been built? Or whether we'd build the elevated 93 or the Inner Belt, then replace the elevated 93 with CAT later as in real life?

I'm going to assume you meant the former, since it's a more interesting hypo. Tough one, too. If the Inner Belt had been built instead of either the Pike or 93, Boston would be a lot more like Paris, with a cohesive inner core and a serious barrier between it and outer neighborhoods. Less of Boston's better architectural stock would have been destroyed (no contest between Haymarket Sq. and Cambridgeport). Arguably, Boston would have retained a lot more attractiveness vs. Cambridge, where Central Square would have probably suffered from blight into the present day. There probably wouldn't have been as much of a different effect due to the southern part of the Inner Belt, since Melena Cass already forms a formidable barrier there anyway. Hard to tell whether Longwood would have suffered or benefitted from increased highway proximity; it would have probably been a much more autocentric place, though. The Newmarket area / South Bay, on the other hand, would have been much more attractive and developable than today, and gentrification/development in Southie probably would have begun much earlier and had been more advanced by now.

Honestly, I think it might be a draw.

CZ -- the Pike was always coming along with or without the Inner Belt -- there already was the great wasteland of rails that cut the Back Bay off from the South End -- the vast majority of the Pike was built on already existing rail ROW

Similarly the Southeast Expressway had been in the plans from almost the time that planning began on Rt-128 (beginingin the 1920's and 30's as a numbered route and completed as limited access even before President Eisenhower launched the Interstates)

The anti-highway caucus on the Forum are living in some "Revisionist History Fantasyland" - Massachusetts was always one of the leading states in highway planning and construction -- and much of it began when South Station was still the busiest rail venue in the World and trolleys ran in streets all over

For example the Tobin Bridge and the Calahan Tunel were designed and then built to connect to the Fitzgerald Expresway aka the Central Artery through the middle of downtown Boston [from Wiki articles]:

Tobin Bridge:

"The Maurice J. Tobin Memorial Bridge (formerly and still sometimes referred to as the Mystic River Bridge... the largest in New England... was erected between 1948 and 1950 and opened to traffic on February 2, 1950 ... $27 million in bonds used to finance the bridge's construction were retired in 1978..... In 1967, renamed in honor of Maurice J. Tobin, former Boston mayor and Massachusetts governor. During his term in office (1945–1947), Tobin created Massport and ordered the construction of the Mystic River Bridge...."

Callahan Tunnel:

"The Callahan Tunnel, officially the Lieutenant William F. Callahan Tunnel is one of four tunnels....carries motor vehicles from the North End to Logan International Airport and Route 1A in East Boston....opened in 1961. It was named for the son of Turnpike chairman William F. Callahan, who was killed in Italy just days before the end of World War II...."

Fitzgerald Expressway:

"The John F. Fitzgerald Expressway, known locally as the Central Artery, is a section of freeway in downtown Boston, Massachusetts, designated as Interstate 93, U.S. Route 1 and Route 3. It was initially constructed in the 1950s as a partly elevated and partly tunneled divided highway.... runs from the Massachusetts Avenue Connector just beyond Andrew Square in South Boston north to the split with U.S. Route 1 in Charlestown.... was planned as early as the 1920s.....

The above-ground Artery was built in two sections. First was the part north of High Street and Broad Street, to the Tobin Bridge built between 1951 and 1954. Immediately, residents began to hate the new highway and the way it towered over and separated neighborhoods. Due to this opposition, the southern end of the Central Artery through the South Station area was built underground, through what became known as the Dewey Square Tunnel....The final section through the Dewey Square Tunnel and on to the Southeast Expressway at Massachusetts Avenue opened in 1959....

The highway gradually became more and more congested as other highway projects meant to complement the Artery were canceled. These included the Inner Belt project, which would have taken through traffic off the Artery and the Massachusetts Turnpike Extension coming in from the west. The Southwest Expressway which would have tied into the Inner Belt and served as the route of Interstate 95...."

MassPike:

" Plans for the Turnpike date back to at least 1948, when the Western Expressway was being planned. The original section would have connected Boston's Inner Belt to Newton with connections with US 20 and Route 30 for traffic continuing west. Later extensions would take the road to and beyond Worcester. From the beginning, the corridor was included in federal plans for the Interstate Highway System, stretching west to the New York state line and beyond to Albany....

The Massachusetts Turnpike Authority was created in 1952 by a special act of the Massachusetts General Court (legislature) upon the recommendation of Governor Dever and his Commissioner of Public Works, William F. Callahan. (1952 Acts and Resolves chapter 354; 1952 Senate Doc. 1.) The enabling act was modeled upon that of the Mystic River Bridge Authority (1946 Acts and Resolves chapter 562), but several changes were made that would prove of great importance fifty years later. Callahan served as chairman of the Authority until his death in April 1964....

Construction began in 1955, and the whole four-lane road from Route 102 at the state line to Route 128 in Weston opened on May 15, 1957....After political and legal battles related to the Boston Extension inside Route 128, construction began on March 5, 1962, with the chosen alignment running next to the Boston and Albany Railroad and reducing that line to two tracks. In September 1964 the part from Route 128 east to exit 18 (Allston) opened, and the rest was finished on February 18, 1965, taking it to the Central Artery. "

Rt-128:

"Route 128 was assigned by 1927 along local roads, running from Route 138 in Milton around the west side of Boston to Route 107 (Essex Street or Bridge Street) in Salem.....By 1928, it had been extended east to Quincy from its south end along the following streets, ending at the intersection of Route 3 and Route 3A (now Route 3A and Route 53)....The first section of the new Circumferential Highway, in no way the freeway that it is now, was the piece from Route 9 in Wellesley around the south side of Boston to Route 3 (now Route 53) in Hingham. Parts of this were built as new roads, but most of it was along existing roads that were improved to handle the traffic. In 1931, the Massachusetts Department of Public Works acquired a right-of-way from Route 138 in Canton through Westwood, Dedham and Needham to Route 9 in Wellesley. This was mostly 80 feet (24 m) wide, only shrinking to 70 feet (21 m) in Needham, in the area of Great Plain Avenue and the Needham Line. Much of this was along new alignment... The rest of the new highway, from Route 37 east to Route 3 (now Route 53), through Braintree, Weymouth and Hingham, was taken over by the state in 1929. This was all along existing roads, except possibly the part of Park Avenue west of Route 18 in Weymouth....By 1933, the whole Circumferential Highway had been completed, and, except for the piece from Route 9 in Wellesley south to Highland Avenue in Needham, was designated as Route 128. Former Route 128 along Highland Avenue into Needham center was left unnumbered (as was the Circumferential Highway north of Highland Avenue), but the rest of former Route 128, from Needham center east to Quincy, became part of Route 135.....

The route 128 number dates from the origin of the Massachusetts highway system in the 1920s. By the 1950s, it ran from Nantasket Beach in Hull to Gloucester. The first, 27-mile (43 km), section of the current limited-access highway from Braintree to Gloucester was opened in 1951. It was the first limited-access circumferential highway in the United States. "

from the following website:

http://www.bostonroads.com/roads/MA-128/

"As early as 1912, the commonwealth of Massachusetts planned a circumferential arterial road stretching out from a 20-mile radius of downtown Boston, some five miles beyond the 15-mile radius formed by the existing Route 128. Beginning in Gloucester... ending in Cohasset. Serving as a bypass for metropolitan Boston, the route was to connect to radial routes through the inner suburbs to Boston....While a high-speed arterial was never constructed, the Massachusetts Department of Public Works (MassDPW) designated a series of local streets as "Route 128" during the 1920's and early 1930's. Through each community, MA 128 went through the following local streets to form a circumferential route from Hull on the South Shore to Gloucester on the North Shore....

In 1934, newly appointed MassDPW commissioner William F. Callahan unveiled plans for the "Circumferential Highway," a controlled-access highway that would connect radial routes while serving as a beltway around Boston. The beltway concept was not new: five years earlier, the Regional Plan Association (RPA) proposed a limited-access highway around the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area, the precursor to today's I-287. However, the Boston beltway was the first one to move from the concept stage to construction....

From 1936 to 1941, the MassDPW constructed two stretches of the new four-lane MA 128: one southwest of Boston in the Dedham-Westwood area, the other northeast of Boston in the Lynnfield-Peabody-Danvers area. Only partial access was obtained on these early sections: grade-separated cloverleaf interchanges were constructed at important crossroads, but several minor roads were allowed to cross at grade....

The Circumferential Highway was one of many highway projects overseen by Callahan that put thousands of people to work in eastern Massachusetts. Funding for the Circumferential Highway came through the Federal Works Progress Administration (WPA)....

... Work on Route 128 halted altogether with the onset of World War II....

1948, when newly elected Governor Paul Dever reappointed Callahan to his MassDPW post, that work on the Circumferential Highway - now re-christened the "Yankee Division Highway" - had resumed. The Master Highway Plan for the Boston Metropolitan Area released that year stated that the circumferential route would connect the radial expressways then being proposed to run into the Boston urban core.

...Under the Federal Highway Act of 1944, the Federal government paid for half the cost of the new MA 128, while state and local governments paid the remaining funds....

To expedite the completion of the expressway, Callahan selected a route through farms and wetlands, and by doing so, steered clear of town centers. This philosophy, while avoiding the "not in my backyard" ("NIMBY") syndrome that doomed future projects, was derided by business leaders, realtors and even the New England chapter of the American Automobile Association (AAA), which called the road a "highway to nowhere." Proponents of the highway cited that the new Route 128 would aid in defense mobilization efforts, and bring the recreation areas of the North Shore and South Shore within easy reach of urban areas....

In its original design, Route 128 was to have four 12-foot-wide lanes (two in each direction), with opposing lanes of traffic separated by a 24-foot-wide grassed median. Callahan desired a six-lane design, but the Federal Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) denied Callahan's plan after engineers determined that a four-lane design would handle traffic adequately for 20 years. They estimated that an average section of MA 128 would handle 15,000 vehicles per day (AADT) by 1970, but by 1955, the average section was already handling 30,000 vehicles per day.

Overpasses and bridges, which were designed with steel girders and stone-faced abutments, were constructed with sidewalks not to accommodate pedestrians, but to allow the construction of an additional lane in each direction. Landscaped areas were to separate the highway from the communities through which it passed.

Construction progressed on the Yankee Division Highway in the following sequence:

1951: The MassDPW completed a 22.5-mile-long stretch of MA 128 from EXIT 20 (MA 9) in Wellesley north to EXIT 44 (US 1 and MA 129) in Lynnfield. ..the new section connected to the previously completed Lynnfield-to-Danvers section to the north and east. Because it was built through the farmland and rolling hills of what was then Boston's outer suburbs, construction time was limited to 18 months...

1953: The route was extended north from Danvers to the rotary at EXIT 11 (MA 127 / Washington Street) in Gloucester.....

1955: The existing four-lane MA 128 was reconstructed as a modern six-lane freeway from EXIT 20 (MA 9) in Wellesley south to EXIT 14 (US 1) in Dedham. The southbound lanes were built on new right-of-way, while the northbound lanes were built over the existing four-lane highway. South of US 1 in Dedham, the six-lane highway was extended on new right-of-way to the current I-93 EXIT 2 (MA 138) in Canton. No provisions were made for a future interchange with I-95 (this did not come until the mid-1960's).

1958: The route was extended south from Canton to the "Braintree Split," a "Y-interchange" with the Southeast Expressway (I-93, US 1 and MA 3) and the Pilgrims Highway (MA 3). Another "Y-interchange" was built to connect MA 128 with the Fall River Expressway (MA 24). Construction of this section began in late 1953, but its construction through the Blue Hills Reservation generated controversy.

1959: The route was extended slightly through Gloucester from to its terminus at EXIT 9 (MA 127A / Main Street). This section contains a rotary at EXIT 10 (Rockport Road), which still exists today.

By the time of its completion in 1959, the Yankee Division Highway was estimated to cost $63 million in construction and right-of-way expenses.

For the convenience of motorists, service areas offering automotive and restaurant services were constructed along MA 128 in Wellesley (southbound only), Lexington (northbound only) and Beverly (northbound only). Since these areas where completed before the construction of the Interstate highway system, they were permitted to continue operation, and remain open to this day.

Original design plans also called for the construction of a mass transit line running along the median of MA 128, and bicycle paths and hiking trails along the landscaped areas bordering the expressway. These plans never were implemented."