As condos Squeeze In, Space is Not All That's Lost

By Andreae Downs

Globe Correspondent / April 6, 2008

As in many a leafy suburb, small houses on big lots are being torn down in Allston and Brighton. They're being replaced not by pricey McMansions, but pricey McCondos.

Slowly but steadily, neighbors say, multiunit town houses or condos are replacing single-family homes on lots from 4,000 to 20,000 square feet. And when tearing down is impossible - because a property is historic or the developer wants to avoid neighborhood opposition - builders are adding homes to back and side yards.

A striking example is 115 Union St. in Brighton. The original house remains on the 4,500-square-foot property, but three apartments are being added to the side and rear yards, filling the lot.

"It's insidious creep," said Charlie Vasiliades, who has lived in the Oak Square neighborhood for all 50 years of his life. "I'm not against growth, but there's a way to do it. Cramming the biggest town house possible into every lot ain't the way."

Paul Berkeley, president of the Allston Civic Association, agrees. "Zoning isn't created to max out neighborhoods, but that's what happening," he said.

"Our old houses, often big houses, are located on big 10,000- to 15,000-square-foot lots. When they are knocked down, it removes the historic fabric of the neighborhood and adds density."

Norman O'Grady, owner of Prime Realty Group in Brighton, said the new homes often include modern conveniences the old houses lacked: granite countertops, central air, Jacuzzis. And they are selling well, typically from $350,000 to $400,000, he said.

"It's what young professionals are looking for," he said. "A lot are moving into the neighborhood because of the easy access to downtown."

The number of families, on the other hand, is shrinking because of the rising cost of housing or a desire for better schools.

The changing profile of homeowners was evident at a recent open house for a three-story, two-family building near Cleveland Circle that is now owner occupied. "I'd say about half were families interested in living there," said Re/Max agent Dave Diveccia, "and the other half were investors."

Though Allston and Brighton remain more affordable than Cambridge or Brookline, and some other parts of Boston, the trend seems to apply to all.

In North Brookline, for example, multifamily buildings are going in where large single-families stood, or units are being added to multifamily homes, said Martin Rosenthal, a Town Meeting member. As a result, Town Meeting has started changing the zoning on parcels to prevent further crowding.

"We're losing that little vestige of a suburban atmosphere and greenery," he said. "Part of what attracts people here is the urban-suburban mix, but when you subtract the suburban parts, you lose something."

High-end conversions and new condos in Brookline and Jamaica Plain are selling well, and for higher prices, "even in a down market," said Tracy Clark, an agent with Chobee Hoy Associates Real Estate Inc. In these neighborhoods, they command $800,000 and up - though a $1 million-plus unit she was watching in Brookline was rented to Red Sox pitcher Daisuke Matsuzaka for an undisclosed amount.

In Allston-Brighton, Clark was unable to find condos for more than $800,000. The highest-priced units are town houses at 1304-1312 Commonwealth Ave. - 2,125 square feet, three bedrooms, 2.5 baths, parking, new construction, offered for $599,900, she said.

more stories like this

Cambridge faces slightly different issues, primarily because of strict city controls on development, said real estate agent Barbara Currier.

"It's virtually impossible to tear a building down; it's extremely rare," she said. "It's extremely difficult even to put a dormer on."

Instead, Currier said, many owners gut buildings "to the skivvies" and rebuild the inside -making a two-family into a single family with an au pair unit in the basement or attic, for example.

The City of Boston's database does not tabulate these types of developments, but a quick survey of Brighton residents turned up reports of at least 10 tear-downs and another four large additions around their neighborhood in the last decade.

A search of city building permits for the last two years turned up another three Brighton homes and an Allston home - not including one destroyed by fire - that had permits for demolition. Add to that a historic home on a 20,000-square-foot lot on Murdock Street in Brighton, where neighbors are fighting to save it from the wrecking ball.

Neighbors in North Allston pointed to at least three tear-downs - confirmed in the city's database - that were completed in the last five to 10 years in a crescent of residences between the Mass. Pike and Western Avenue and near St. Anthony's Catholic Church.

The Boston Landmarks Commission reviews the razing of any building more than 50 years old. But commission member Bill Marchione, who also is president of the Brighton Allston Historical Society, acknowledges "there's not much we can do under the Landmarks Act" to halt development, other than invoke the city's 90-day demolition delay.

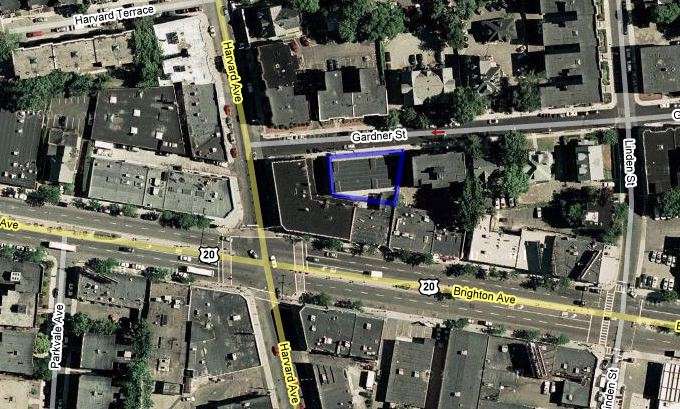

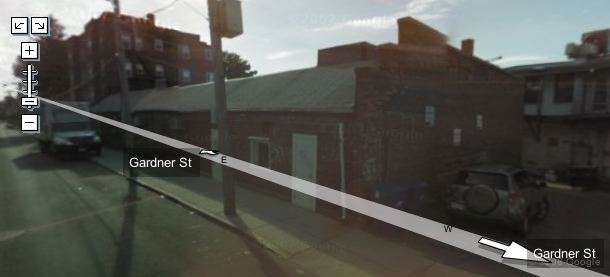

Case in point: 34 Raymond St. in North Allston. Identified by the Allston Civic Association as one of the oldest houses in the neighborhood, the single-family Victorian at the corner of Westford had a large lawn and mature trees when it was bought last year for $950,000 and torn down over neighborhood protests.

Going up on the site are two three-unit town houses that look like they'll occupy most of the lot. Although developments of this type sometimes require zoning variances, Inspectional Services Department records show that these structures can be built without zoning relief.

Berkeley said his civic association was looking at getting some kind of neighborhood historic designation that might slow demolitions beyond the 90-day delay provided by the city ordinance.

In addition to historic concerns, residents' complaints focus mostly on building density. "The frustration is that we have zoning in the neighborhood, but probably two-thirds of these buildings, by my guess, violated zoning," said Vasiliades, the Oak Square resident and Brighton Allston Historical Society vice president. But he said developers receive zoning variances anyway.

According to Berkeley, "Variances are supposed to relieve hardship. But more often they are granted for economic development because otherwise the developer isn't getting a reasonable return on his investment."

Derric Small, principal administrative assistant to Boston's Board of Appeal, said that each case depends on the character of the neighborhood. A single-family house surrounded by three-deckers can be converted to a three-family without a variance, for instance. The side-yard requirement for West Roxbury is probably 10 feet between houses, Small said, while it would be more like 2 feet in the North End.

He acknowledged that the zoning board is flexible in granting relief. "It's fairly easy to get a variance, depending on how minor it is, of course." But he understands that neighbors might be starting to feel squeezed as larger yards disappear around multifamily homes.

"They shouldn't feel alone," Small said of Allston and Brighton neighbors. "It's happening all over the city."

? Copyright 2008 Globe Newspaper Company.