Hear that giant sucking sound? that's the sound of Massachusetts money going down the Connecticut casino drain. You're against gambling? Then shut down the Mass lottery - it's more regressive than casinos. Just don't take local aid to your city or town and then say you're against gambling.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MA Casino Developments

- Thread starter TheRifleman

- Start date

Beton Brut

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,382

- Reaction score

- 338

In this scenario, I think the prospect of voter passage is actually less. I think once the liberal sensibilities of JP/South End, plus the general patrician attitudes of Beacon Hill and the Back Bay become involved - the road toward passage gets a lot muddier.

There's more than a kernel of truth in this observation.

I still want to know what happens if Suffolk decides to locate the entire gaming facility on the Revere side of the property. As a Revere resident, I can't envision any scenario where Revere would vote this down. As an added quirk, Suffolk also owns the Wonderland property. If the vote in Eastie/Boston fails and the Revolution soccer stadium proves a bust - Wonderland could be their Ace in the hole - pun intended.

We've posed this question to the Gaming Commission; they've yet to respond.

In my opinion, the Wonderland property lacks the acreage to build at the scale to make the investment worthwhile for Caesars. It's also an infrastructure nightmare. You are correct to assume that the thugs who govern Revere are licking their chops...

...you better have this avenue covered. Jdrinboston brings up a real good point about how Revere could be the Ace of spades.

The organized opposition has taken root in Revere as well.

You're against gambling? Then shut down the Mass lottery - it's more regressive than casinos. Just don't take local aid to your city or town and then say you're against gambling.

To be clear, I'm not against gambling; I'm against the content of the legislation (i.e. the way it was written) and the way it was brought into law (i.e. on Beacon Hill instead of at the ballot box).

I've heard your argument about the Lottery for quite some time. For every dollar spent on the Lottery, $0.22 comes back to cities and towns. The projected aggregated return via the gambling legislation is roughly $0.07. You're a sharp guy, Jon -- don't you think that the introduction of casinos into the "gambling landscape" will cannibalize the Lottery? What happens when that $0.22 is reduced? Who makes up the difference? The taxpayers do...

I agree and also feel a casino is not good for any part of the city and any nearby cities/towns. I personally don't want a casino within 128, but that's just me.

Get a mitt and get in the game. If you wanna help, PM me.

Last edited:

TheRifleman

Banned

- Joined

- Sep 25, 2008

- Messages

- 4,431

- Reaction score

- 0

^^^^^^^^^^^^

How you like them APPLES?

How you like them APPLES?

To be clear, I'm not against gambling; I'm against the content of the legislation (i.e. the way it was written) and the way it was brought into law (on Beacon Hill instead of at the ballot box).

I don't see why this would have to go to the ballot box. This sounds like a perfect solution for the representative democracy we have set up.

Ron Newman

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 30, 2006

- Messages

- 8,395

- Reaction score

- 13

(regarding the proposal for a casino on Route 99 in Everett)

It's about a mile from I-93 (and from Sullivan Square T station, though that's an unpleasant walk). Suffolk Downs is much further away from any expressway.

Riff is right on this one - so little infrastructure. Road access from Boston is poor. No transit. No expressway access.

It's about a mile from I-93 (and from Sullivan Square T station, though that's an unpleasant walk). Suffolk Downs is much further away from any expressway.

(regarding the proposal for a casino on Route 99 in Everett)

It's about a mile from I-93 (and from Sullivan Square T station, though that's an unpleasant walk). Suffolk Downs is much further away from any expressway.

True that it is near Sullivan. That would require much transportation mitigation to make Sullivan Sq. navigable/manageable for the users. See this thread: http://www.archboston.org/community/showthread.php?t=1849&highlight=sullivan+square&page=4. Not sure how Boston would accept that if they lost the casino at Suffolk Downs, though.

AmericanFolkLegend

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jun 29, 2009

- Messages

- 2,214

- Reaction score

- 248

I think a lot of people aren't against gambling per se. They're against an urban casino (as opposed to a destination casino).

Beton Brut

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,382

- Reaction score

- 338

I don't see why this would have to go to the ballot box. This sounds like a perfect solution for the representative democracy we have set up.

Representative Thugocracy, featuring:

Happy reading...

KentXie

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,195

- Reaction score

- 766

I think a lot of people aren't against gambling per se. They're against an urban casino (as opposed to a destination casino).

This.

I think a lot of people aren't against gambling per se. They're against an urban casino (as opposed to a destination casino).

That's my thinking. I have zero issues with casinos coming to Mass, just wish the Pols would be a bit smarter about where they want to put them.

Also, will the alcohol situation and pricing be an issue? I thought I remember reading some bar owners were annoyed that the casino(s) would be able to offer drink specials.

I've heard your argument about the Lottery for quite some time. For every dollar spent on the Lottery, $0.22 comes back to cities and towns. The projected aggregated return via the gambling legislation is roughly $0.07. You're a sharp guy, Jon -- don't you think that the introduction of casinos into the "gambling landscape" will cannibalize the Lottery? What happens when that $0.22 is reduced? Who makes up the difference? The taxpayers do...

.

With casinos in state, money stops bleeding across the border. Money spent out of state is pure loss. Jobs are created. And by the way - the same people who go to Foxwoods buy scratch tickets - write it down.

And this: "Who makes up the difference? The taxpayers do... "

So in other words, you like this regressive tax - better it comes out of the working class than Bo-bos who sniff their noses at lottery tickets. By 'the taxpayer' you mean people like yourself, right? Personally, I'm against taxes like the lottery, just like I'm against alcohol and cigarette taxes. All taxes should be broad based. If the state can only raise taxes by sticking it to smokers and taking advantage of working poor dreams, then they shouldn't spend the money.

And while you may not be against gambling in principle, the anti-casino crowd in this state certainly is.

SeamusMcFly

Senior Member

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2008

- Messages

- 2,050

- Reaction score

- 110

I think a lot of people aren't against gambling per se. They're against an urban casino (as opposed to a destination casino).

By destination casino I take that to mean something like Foxwoods that is all inclusive. Personally I am against that, and the incredible amount of acreage used to support this. I much prefer the urban concept where most of the amenaties and infrastructure already exist or new amenities would benefit the City and its residents.

Last edited:

AmericanFolkLegend

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jun 29, 2009

- Messages

- 2,214

- Reaction score

- 248

By destination casino I take that to mean something like Foxwoods that is all inclusive. Personally I am against that, and the incredible amount of acreage used to support this. I much prefer the urban concept where most of the amenaties and infrastructure already exist or new amenities would benefit the City and its residents.

I appreciate what you're getting at, but I don't think most of the amenities associated with a casino benefit "the City and its residents" anyway. What are those amenities that the average Bostonian would benefit from? Free cocktails?

The benefits of a destination casino (at least for me) are:

1. Destination casinos are a less regressive form of taxation than urban casinos.

2. The externalities of a destination casino can be (at least partially) contained.

You mention a destination casino as being a poor use of land (presumably because it's spread out). But if that's your concern, that can be addressed by zoning. I think a much poorer use of land is a 100K SF gaming floor in the middle of a dense city.

SeamusMcFly

Senior Member

- Joined

- Apr 3, 2008

- Messages

- 2,050

- Reaction score

- 110

I appreciate what you're getting at, but I don't think most of the amenities associated with a casino benefit "the City and its residents" anyway. What are those amenities that the average Bostonian would benefit from? Free cocktails?

The benefits of a destination casino (at least for me) are:

1. Destination casinos are a less regressive form of taxation than urban casinos.

2. The externalities of a destination casino can be (at least partially) contained.

You mention a destination casino as being a poor use of land (presumably because it's spread out). But if that's your concern, that can be addressed by zoning. I think a much poorer use of land is a 100K SF gaming floor in the middle of a dense city.

By amenities I meant restauants, clubs, music venues that if on the block or the next block would be used by residents, visitors to the area, and gamblers, but do not need to be contained within the casino proper. Destination casinos typically wrap all of this into one big structure. When externalized into an urban environment, this can turn a neighborhood into a 24/7 neighborhood versus one 24 hour building.

I will never bite on the gambling is a tax on the poor line. It may be a tax on the stupid, or a fun way to win or lose money for those who can afford such luxuries.

It's hard to provide parking, hotels, etc. at a destination casino without using a heap of land. On the other hand, the 100k sf of gaming space can be hidden pretty well in a podium in an urban area, and that podium can serve as the base for multiple, separate towers for hotels. This breaks up the superblockery of the development while providing interconnectability of the complex (think more along the lines of city center in Vegas than Marina Bay Sands.)

Beton Brut

Senior Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 4,382

- Reaction score

- 338

The New York Daily News said:Gambling away our cities

Why New Yorkers must fight the drive to legalize full-scale gaming

BY RICHARD FLORIDA / NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 25, 2012

Early in September, Sheldon Adelson, the 79-year-old founder of The Sands (and a lavish political donor — he contributed more than $50 million to help Mitt Romney and other Republicans get elected), announced that Madrid will be home to a massive EuroVegas gambling and entertainment complex. When construction is completed in about 10 years, there will be six casinos with 18,000 slot machines and a dozen hotels with 36,000 rooms.

Adelson would like to do something similar in New York City, on the site of the Jacob K. Javits Center on the West Side. As New York State begins the process of amending its constitution to allow up to seven new full-scale private casinos, eager gaming interests have flooded the state with lobbying money and campaign contributions, according to a report by Common Cause New York.

In Miami, the Genting Group — the same Malaysian company that operates the casino at Aqueduct — has proposed a $3 billion plus city-within-a-city on the site of the Miami Herald building, which it has already purchased for $236 million. The project would include two condo towers, four luxury hotels, 50 restaurants, 60 luxury shops and a yacht marina.

Casinos have either been built or proposed in Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, Boston, Toronto and countless other cities across the United States and the world.

This “casinoization” of just about everywhere has been going on for some time. Three decades ago, only three American cities — Las Vegas, Reno and Atlantic City — had casinos. Today, gambling is legal in more than 40 states, and roughly 2,000 gambling venues can be found across America.

Gambling generates about $90 billion in revenues annually, a figure that is projected to expand to $115 billion by 2015. A third of this flows from casinos.

For politicians, casino money is a powerful allure. Casinos offer a potent triple whammy of big ground-breakings; new jobs in construction, hospitality and gaming tables; and substantial new sources of public revenue. “t’s important to look at other sources other than taxing people to death,” Florida City’s Mayor Otis Wallace (whose city just proposed a 25-acre horse racing, jai alai and casino complex), told the Miami Herald.

While politicians and casino magnates seek to sell gambling complexes to the public as magic economic bullets, virtually every independent economic development expert disagrees — and they have the studies to back it up.

More than a decade ago, the bipartisan National Gambling Impact Study Commission’s Final Report concluded that while the introduction of gambling to highly depressed areas may create an economic boost, it “has the negative consequence of placing the lure of gambling proximate to individuals with few financial resources.”

When gambling is added in more prosperous places, “the benefits to other, more deserving places are diminished due to the new competition. And as competition for the gambling dollar intensifies, gambling spreads, bringing with it more and more of the social ills that led us to restrict gambling in the first place.”

In his 2004 book “Gambling in America: Costs and Benefits,” Baylor University economist Earl Grinols totaled the added costs that cities must pay in increased crime, bankruptcies, lost productivity and diminished social capital once they introduce casinos to their economic mix. He found that casino gambling generates roughly $166 in social costs for every $54 of economic benefit. Based on this, he estimates that the “costs of problem and pathological gambling are comparable to the value of the lost output of an additional recession in the economy every four years.”

Atlantic City’s first legal casino opened in 1978 amid expectations of economic spillover in the form of retail businesses, restaurants, rising property values and jobs. But a study conducted 13 years later found that any “anticipated multiplier effect has not moved much beyond the core industry . . . Half of the population still receives public assistance, and city services continue to be substandard. Social problems, including increased crime and prostitution, are worse than ever. Since most people holding the better casino jobs live in Atlantic City suburbs, they contribute little directly to the city.”

Casino cities are “dual cities” defined by “two-tiered economies,” according to John Hannigan of the University of Toronto. “[C]rack cocaine-addled prostitutes struggle to survive in the underground economy that flourishes . . . in close proximity to the glittering casinos.”

The typical customer of an urban casino is neither a tourist nor a deep-pocketed whale, but a local of modest means. Dave Jonas, president of Philadelphia’s Parx Casino, told the Pennsylvania Gaming Congress in 2010 that his typical customer spends $25 or $30 dollars a visit — and many of them return three, four and five times a week.

Much of the tax revenue produced by gambling comes out of their pockets. A “tax on ignorance” is what Warren Buffett once called it.

“I find it socially revolting when a government preys on the weakness of its citizenry rather than serving them,” he added.

Even the profits from vice are subject to diminishing returns. According to a report from the University of Las Vegas’ Center for Gaming Research released in March 2012, Atlantic City’s gambling revenues have fallen by more than 36% since 2006, when the first casino in nearby Pennsylvania opened its doors.

The city had been plowing $100 million into restoring its vaunted Steel Pier, upgrading its beach and boardwalk, making improvements to the Atlantic City Historical Museum and the Atlantic City Arts Center — efforts that suffered a devastating setback from superstorm Sandy last month.

Competition from Bay Area tribal casinos has taken a devastating toll on Reno, which has seen its gambling revenues fall by a third since 2000. Its leaders hope that a $1 billion Apple data center and a 78-lane National Bowling Stadium will help revitalize the city.

Meanwhile, Las Vegas is trying to reduce its dependence on casinos, transforming itself into part clubland, part Disneyfied family resort destination — and is emerging as the world’s leading destination for high-end business conferences. The city is working to create mixed-use urban living around the huge City Center complex on the Strip, while Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh has invested $350 million in a live-work-play district in the area surrounding the old city hall, where he has opened his new corporate headquarters.

It’s ironic: Even as America’s original gambling resorts seek to remake themselves, countless struggling cities are looking to gamble their way out of these tough times.

The late Susan Strange read the writing on the wall in her landmark 1986 book “Casino Capitalism,” in which she compared the whole economy to a giant game of Snake and Ladders: “This cannot but have grave consequences,” she wrote. “When sheer luck begins to take over . . . then inevitably faith and confidence in the social and political system quickly fades.”

The recent surge in gaming across American cities is an outgrowth of this system of casino capitalism, which, as Daniel Denvir wrote in Salon last March, “feeds on America’s job insecurity; people, whether gambling or seeking employment, have fewer viable ways to make good money.” Indeed, casino capitalism has given way to casino fiscalism.

While gamblers might fool themselves into thinking that they can get something for nothing, public officials and civic leaders should know better. “I don’t think the state should be in the position of selling the needle,” Buffett said.

“When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino,” John Maynard Keynes famously wrote in “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money,” “the job is likely to be ill-done.”

It could be the punch line of a joke, if it weren’t so tragic.

Richard Florida is director of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto, Global Research Professor at NYU and senior editor at The Atlantic, where he co-founded Atlantic Cities.

.

JohnAKeith

Senior Member

- Joined

- Dec 24, 2008

- Messages

- 4,337

- Reaction score

- 82

Sounds like a perfect idea!

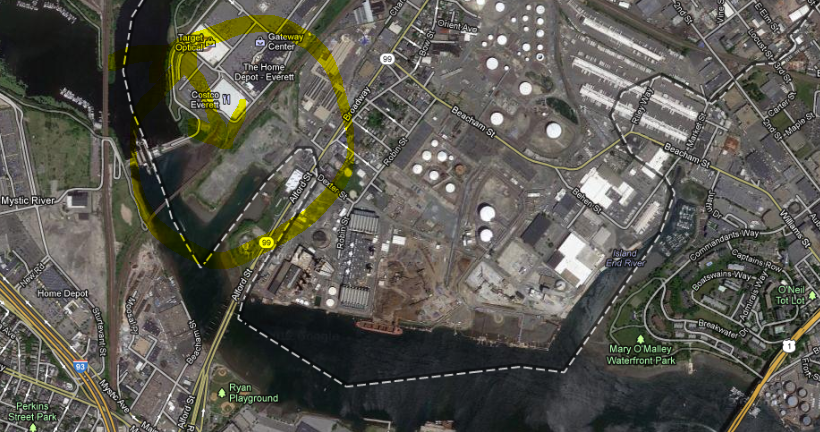

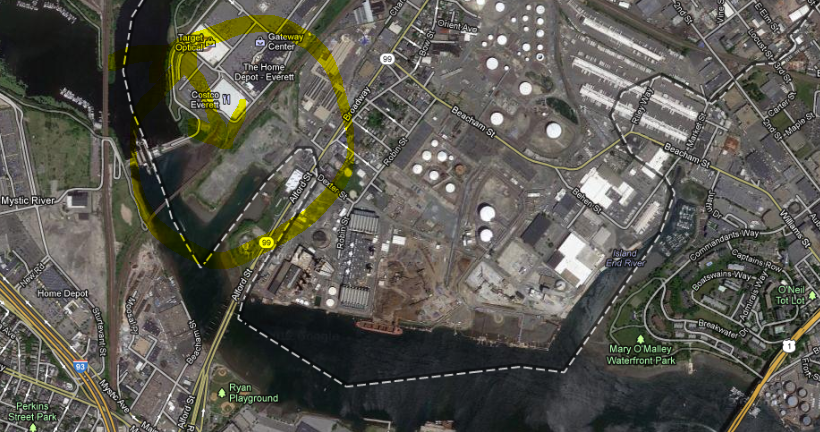

Where is this, specifically? Is it here?

How would this figure in to the Green Line extension to Medford? That's more to the southwest?

But you could build a spur off of the Orange Line at Sullivan Square (or, a commuter rail stop) and make it convenient!

Vegas mogul Steve Wynn pursuing Everett casino site

By Mark Arsenault, Globe Staff

Mark Arsenault can be reached at marsenault@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @bostonglobemark

Where is this, specifically? Is it here?

How would this figure in to the Green Line extension to Medford? That's more to the southwest?

But you could build a spur off of the Orange Line at Sullivan Square (or, a commuter rail stop) and make it convenient!

Vegas mogul Steve Wynn pursuing Everett casino site

By Mark Arsenault, Globe Staff

Las Vegas casino mogul Steve Wynn, who failed to persuade Foxborough to accept a lavish $1 billion gambling resort, is investigating land on the Mystic River for a possible casino bid in Everett, which would create a clash among gambling titans for the state’s most lucrative casino license.

Wynn, the creator of iconic hotels on the Vegas Strip, such as Bellagio, the Mirage, and Treasure Island, is expected in Everett this week to personally view the site, Mayor Carlo DeMaria’s office confirmed to the Globe this afternoon. The mayor’s office would not say when Wynn is to arrive, but another source said the casino billionaire is due in Everett on Wednesday.

A top Wynn Resorts executive, Kim Sinatra, viewed the land, known as the former Monsanto Chemical site, within the past few weeks.

Wynn’s return to the Massachusetts market would create a competition for the sole greater Boston casino license between two of the biggest names in casino gambling. Suffolk Downs, in partnership with casino giant Caesars Entertainment, has already applied for casino development rights for the track in East Boston.

Under the 2011 Massachusetts casino law, the state gambling commission can issue up to three licenses for resort-style casinos, no more than one in each of three regions of the state.

Competition has been robust in Western Massachusetts, with three proposals for Springfield, one for Palmer, and a new prospect in Holyoke. Commercial casino development is on hold in the southeast to allow the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe time to make progress on a tribal casino, approved under federal law.

The greater Boston area has only one formal applicant, Suffolk Downs and Caesars; the gambling commission has been trying to encourage competition.

Mark Arsenault can be reached at marsenault@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @bostonglobemark

BostonUrbEx

Senior Member

- Joined

- Mar 13, 2010

- Messages

- 4,340

- Reaction score

- 130

Perfect excuse to get Urban Ring going. Start with Phase I: heavy rail from Airport to Sullivan Square via Chelsea. Also pushes forward on opening up the Amelia Earheart dam to pedestrian/bike traffic, and getting the Northern Strand Community Trail extended over the Mystic, perhaps.

I wonder if Wynn knows how contaminated this parcel is. The Mystic View mall/Target had some serious cleanup and a cap. This is part of the same Monsanto plant, I believe. I expect that there is a pretty strong Activity and Use Limitation. I will spend more time looking at the 21e DEP site to find it.

Perfect excuse to get Urban Ring going. Start with Phase I: heavy rail from Airport to Sullivan Square via Chelsea. Also pushes forward on opening up the Amelia Earheart dam to pedestrian/bike traffic, and getting the Northern Strand Community Trail extended over the Mystic, perhaps.

How about the developer/owner kicks in some money as well.

AmericanFolkLegend

Senior Member

- Joined

- Jun 29, 2009

- Messages

- 2,214

- Reaction score

- 248

Yeah, that's right John. There was talk (in BBJ I think) about a direct ramp to the parcel from I-93. Because trying to put all that traffic on 99 is really a non-starter as far as I'm concerned.

On contamination: we did some utility work for NSTAR over there. Basically ran a high voltage underground line from the power plant to a substation over by the commuter rail tracks. I'm pretty sure we weren't technically even on the Monsanto site, and all the dirt was so contaminated it had to be shipped out of state.

On contamination: we did some utility work for NSTAR over there. Basically ran a high voltage underground line from the power plant to a substation over by the commuter rail tracks. I'm pretty sure we weren't technically even on the Monsanto site, and all the dirt was so contaminated it had to be shipped out of state.