The Seaport district plan, a kind of owner's manual for development of the South Boston waterfront, arrived at City Hall from the printer yesterday amid high expectations that the glossy bound document will guide building on Boston's new frontier for decades to come.There are few surprises in the 115-page booklet beyond what Mayor Thomas M. Menino previewed Jan. 5 at a Parkman House news conference. The plan calls for 5,000 to 8,000 units of housing, small-scaled city blocks and generally low-level buildings, along with parks and civic destinations to be funded by the developers of hotels, office buildings, condominiums, and restaurants.

But now that city officials have the actual planning document in hand, the focus is expected to turn to specific projects. The plan will be tested for the first time in coming weeks when the Chicago-based Pritzker family, owners of the Hyatt hotel chain, unveils plans for a hotel, office, retail, condo, and office complex on Fan Pier, between the new federal courthouse and Anthony's Pier 4 restaurant.

The Pritzkers and local partners Spaulding & Slye will be asked to transform the outer reaches of Fan Pier -- now rubble-strewn or used for parking -- into a waterside park and public destination point, according to the plan. Other landowners farther back from the water's edge will be required to contribute to a central fund for public amenities both in the Seaport and the Harbor Islands. The Pritzker project will also be a test case for the mix of uses, and the density and height of waterfront development that city planners say they will allow.

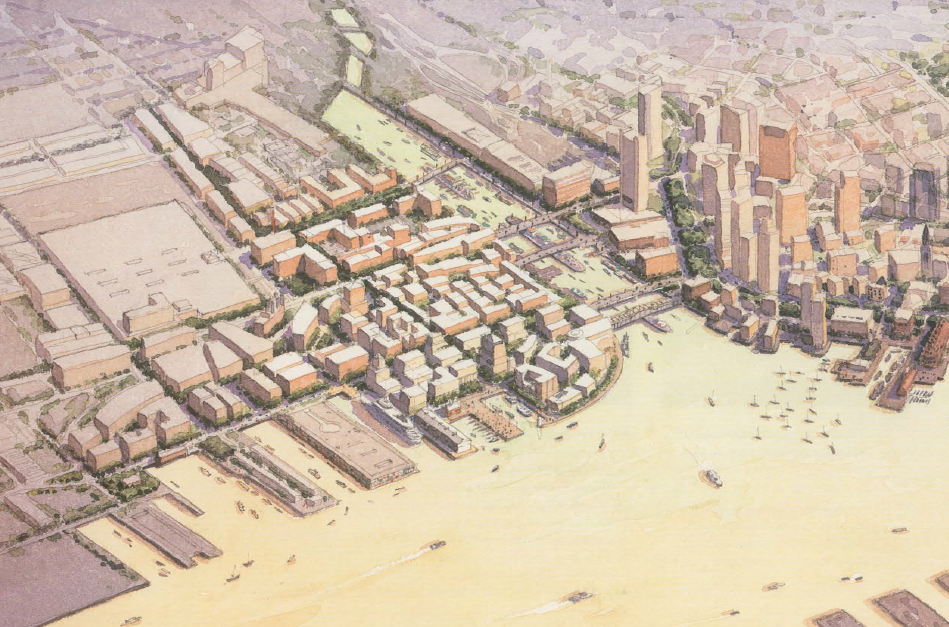

The original Pritzker plan for Fan Pier called for tall buildings, raising fears that the harbor could be walled off to pedestrians. The city's new master plan encourages such buildings away from the water, concentrated in the area between New Northern Avenue and Summer Street; the heights of buildings will then "slope down" in all four directions from that concentration of development, according to the plan.

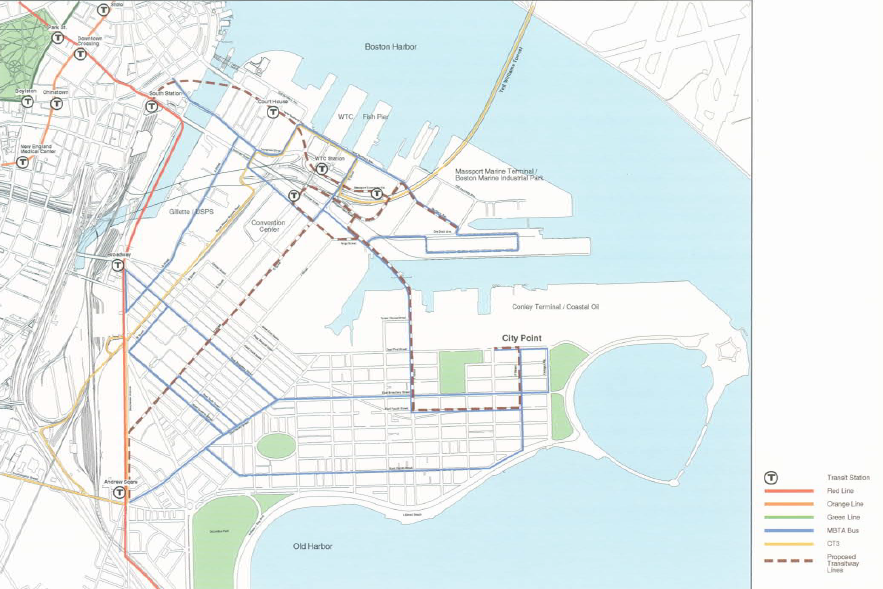

The Seaport document itself, which includes aerial photos, maps, and artist renderings of what the future waterfront could look like, contains no strict zoning rules, but rather lays out general guidelines for developers. In fact, it is titled the "Seaport Public Realm Plan" and not "master plan," underscoring the Boston Redevelopment Authority's attempt to lay down only a basic foundation for future construction. Urban design guidelines and specific zoning regulations are due out later this year.BRA director Thomas N. O'Brien said yesterday the plan represents a consensus from hundreds of community meetings and consultations with private urban planners and design professionals. "It's something that when you stand back, all of us, and anybody who really cares about this area, can really be proud of. We took in a lot of comments that didn't always match up with each other, and tried to sort it all out."

The Seaport is universally regarded as the last major expanse of developable land close to the core of Boston, with some of the most prized real estate on the East Coast, commanding spectacular views of the city skyline. It is also expected to be a major economic engine; planners anticipate up to 20 million square feet of development in the 1,000-acre area, producing 16,000 construction jobs and 30,000 permanent new jobs.

Disagreement about several key aspects of the plan remain. For example, while the BRA wants to create a "24-hour neighborhood," City Council President James M. Kelly has said he wants to see no more than 4,000 housing units in the Seaport. Open space advocates say there is insufficient land set aside for parks. Supporters of the blue-collar jobs in the working port remain skeptical that trucks will be able to get in and out of what in 20 years will resemble Back Bay, as the western sections ofthe waterfront are gentrified.