Plan to untangle avenue divides Charlestown

Uploaded with

ImageShack.us

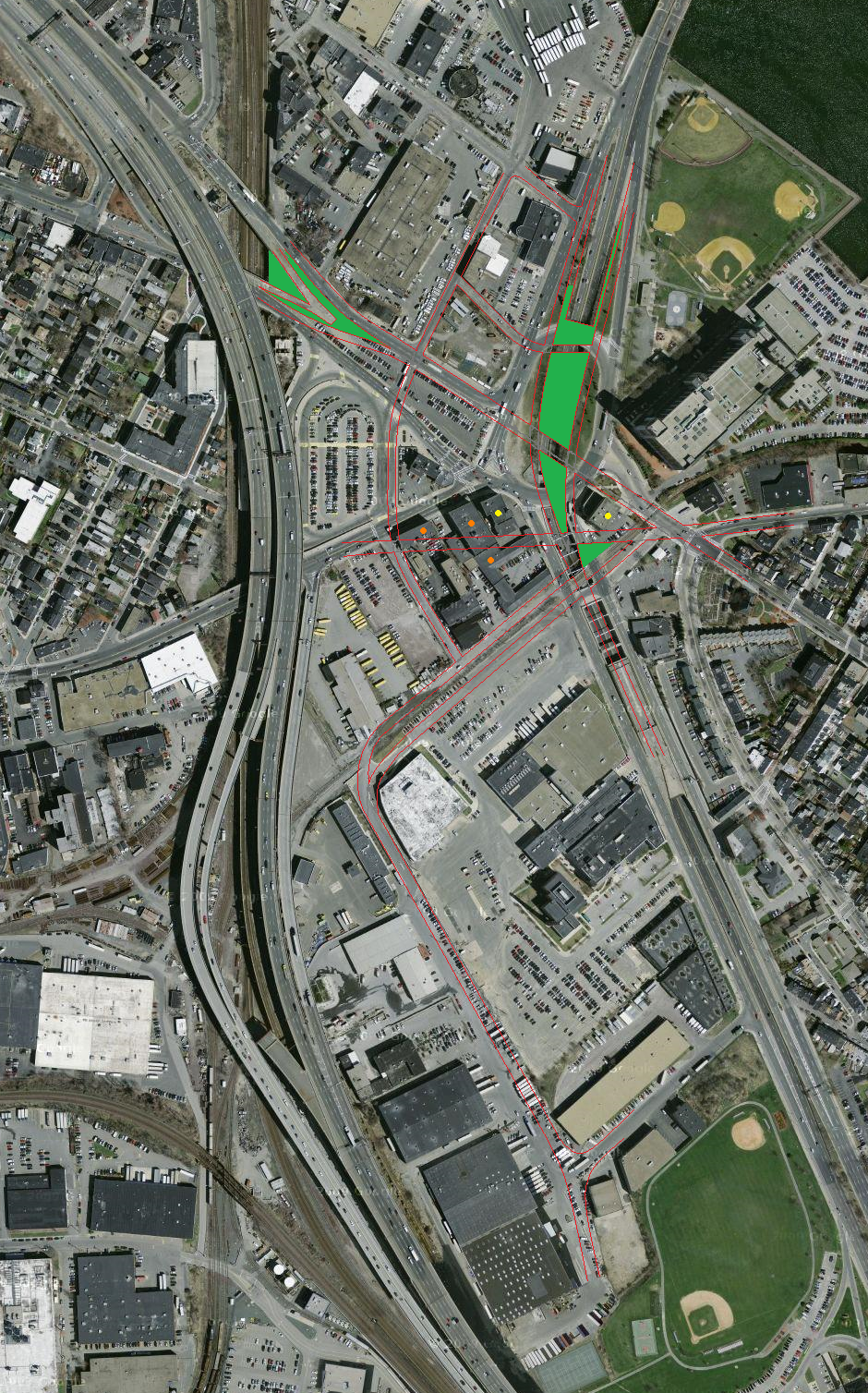

Charlestown’s Rutherford Avenue is a city street masquerading as a highway, a mid-20th-century relic scarred with chain-link fence, orange barrels, and Jersey barriers. Swelling to 10 lanes, split by a median, and nearly free of traffic lights, it invites speeds well over 50 miles per hour. Pedestrians and bicyclists approach at their peril.

On this much, nearly all agree: Rutherford is ugly, crumbling, and must be rebuilt. But the decision on how much it should resemble its old self is roiling the community. Three years into the planning, the debate is as pitched as ever.

Some want Rutherford to become a cross between Commonwealth Avenue and Southwest Corridor Park, a leafy boulevard flanked by a recreational path. Others want it kept mostly as is but rebuilt to last another 50 years and polished around the edges.

Advocates of the leafy option say it would be safer, prettier, livelier, and cheaper to build ($71 million versus $83 million) and maintain. They say it would also knit together divided neighborhoods.

Opponents say it will send drivers scurrying down side streets, seeking detours around the traffic lights.

“There’s nothing more important than this project in . . . making a difference for the neighborhood and making a difference for the city,’’ said Elizabeth Levin, speaking as a Charlestown resident, not in her capacity as a member of the board that oversees the state Department of Transportation. “And yet we don’t seem to be able to take that opportunity . . . because, for some reason, the change makes people nervous.’’

Neighborhood disagreement is common whenever plans emerge about reducing car lanes to accommodate bicycles and pedestrians, even when it involves aging, hulking urban highways like Rutherford, known to outsiders as the anonymous road that barrels past Bunker Hill Community College.

A similar debate flares in Forest Hills, where the state is considering removing the Casey Overpass. There, as with Rutherford, traffic engineers say a better-designed grid of streets and carefully timed lights can handle as much traffic as their counterparts, but residents are dubious.

The Charlestown debate has an added layer, falling roughly along “Townie versus Toonie’’ lines, dividing those raised in Charlestown and recent arrivals who have driven up home prices, those who pronounce it “Rootherford’’ and those who don’t.

Many skeptics have long memories, recalling past instances when government claimed to know best for the people of Charlestown: busing, urban renewal, construction of the towering, and lead-painted Tobin Bridge.

They say the more dramatic Rutherford revision is a ploy to open parcels hemmed in or covered by the existing road for development, generating city taxes while bringing more change - and traffic - to Charlestown.

At a recent meeting, the loudest applause came when Gerard Doherty, an octogenarian former legislator, compared the city’s windy, statistics-heavy defense of the reimagined Rutherford to Communist propaganda.

“Liars figure and figures lie,’’ said Doherty, who managed Edward M. Kennedy’s first Senate race in 1962. “We’re not going to leave - and we’re not going to leave this town - and we’re going to fight and do everything we possibly can!’’

The lack of consensus and distrust of the city has confounded supporters of the more dramatic redesign, which requires faith in traffic engineers. The plan would fill in Rutherford’s two underpasses - where some of its lanes dip below cross streets at Sullivan Square and again by the college - and reconfigure Sullivan’s rotary as a more orderly grid.

That plan appeared to prevail as the community’s choice in January 2010, after more than two dozen meetings with residents during 18 months. The Boston Transportation Department provided seed money for conceptual planning and intended from there to seek federal funds to refine the design and bid for construction.

Then opponents began rallying support - largely among those who had missed the planning sessions - and US Representative Michael Capuano, who represents Charlestown and sits on the House Committee on Transportation, weighed in with concerns of his own.

On its face, narrowing Rutherford and eliminating underpasses would seem to worsen traffic, especially with Sullivan Square already chaotic.

But, since completion of the Big Dig made Interstate 93 more attractive, Rutherford has four times as many lanes as needed even at rush hour, according to Mike Hall, traffic engineer with consultant Tetra Tech Rizzo.

Congestion instead is a result of a pinch point between two other streets merging at the rotary.

Meanwhile, the 2009 closing of the outbound side of the decaying Rutherford underpass also forced traffic into the rotary. A grid, plus improvement of roads in the lightly used industrial-commercial area around Sullivan Square, could ease traffic at Sullivan, said Hall and city officials.

“It’s a complicated thing,’’ said Mark Rosenshein, a member of the elected Charlestown Neighborhood Council, a City Hall advisory board. He is an architect who moved to town in 1998. “It’s not something you can sit down and listen for 10 minutes and get.’’

Bill Galvin, part of a minority on the Neighborhood Council opposed to the plan, said the city has rigged the process to produce results that will be cheaper to maintain and allow more development.

“I have a very, very healthy skepticism of government-hired - or anyone-hired - experts,’’ said Galvin, 68, a lawyer and third-generation Townie. “They have slanted everything to the surface option because that’s what they want.’’

Capuano’s staff participated in the planning process, but he did not raise issues until after it was over, when he approached the city with concerns the plan would worsen traffic. He convened his own meeting last spring that drew more than double any of the earlier planning sessions and gave a second wind to those who want to keep the underpasses.

That frustrated those who hoped he would press for what they view as a progressive plan.

But Capuano, whose support is key to winning federal dollars, said his role is to maximize constituent input. “Being involved is a good thing - as I am - but it doesn’t mean that the people who don’t go to every meeting get ignored,’’ he said.

Capuano said he hopes a compromise can be reached to preserve underpasses while also improving bike and pedestrian options. He bristled at the idea of outsiders claiming to know best.

“I wouldn’t like people from Charlestown coming to Winter Hill and telling me how to do traffic flow,’’ the former Somerville mayor said.

Boston Transportation Commissioner Thomas J. Tinlin said he understands if supporters of the more dramatic redesign feel fatigued, but the city wants to include everyone.

“This has been a long and sometimes arduous process, and tough slogging on occasion,’’ Tinlin said. “One thing I’ve learned in this city is I don’t think the process is really ever over until dirt is moved.’’

Eric Moskowitz can be reached at

emoskowitz@globe.com.