1. tree grows, pulls massive amounts of carbon from the air.... ...man (#deplorables) burns tree in his mancave. puts some carbon back in the air. New tree grows (wood cultivated by man or nature for future generation/s).... pulls carbon back out of the air...

#burning wood is 100% solar energy.

2. tree grows, pulls massive amounts of carbon from the air ....tree dies, rots, puts carbon, gasoil, wood esters, etc back in the air while new tree grows....

esters released to atmosphere found to harm ozone layer.

Gretch at rennlist P&C said:

21 days..............left. It has been a long and painful 8 years.

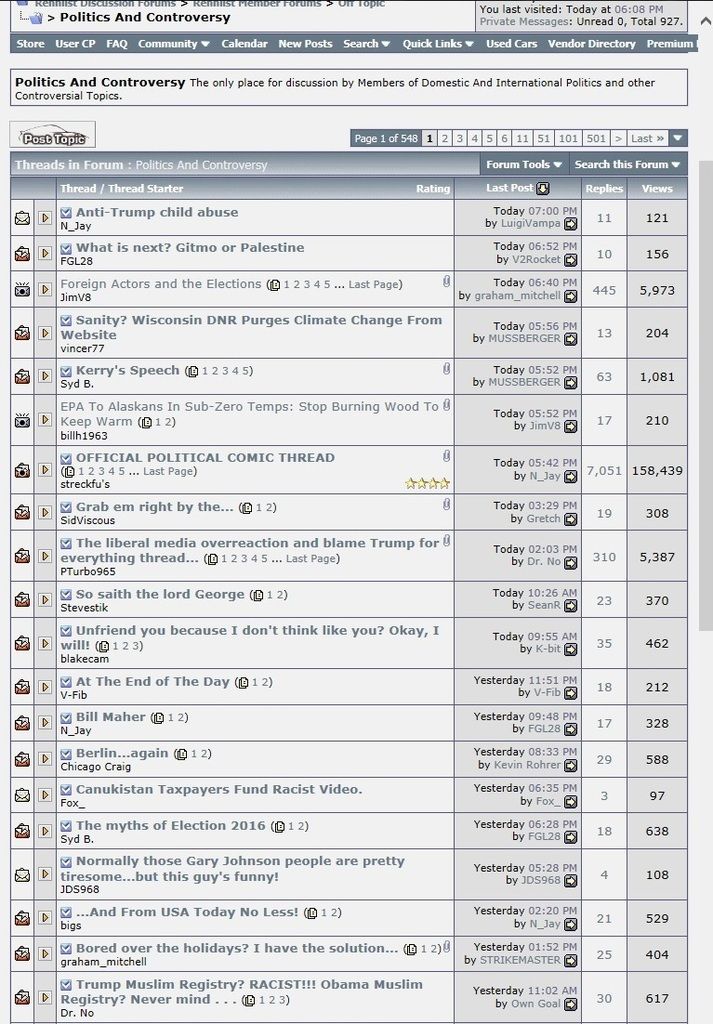

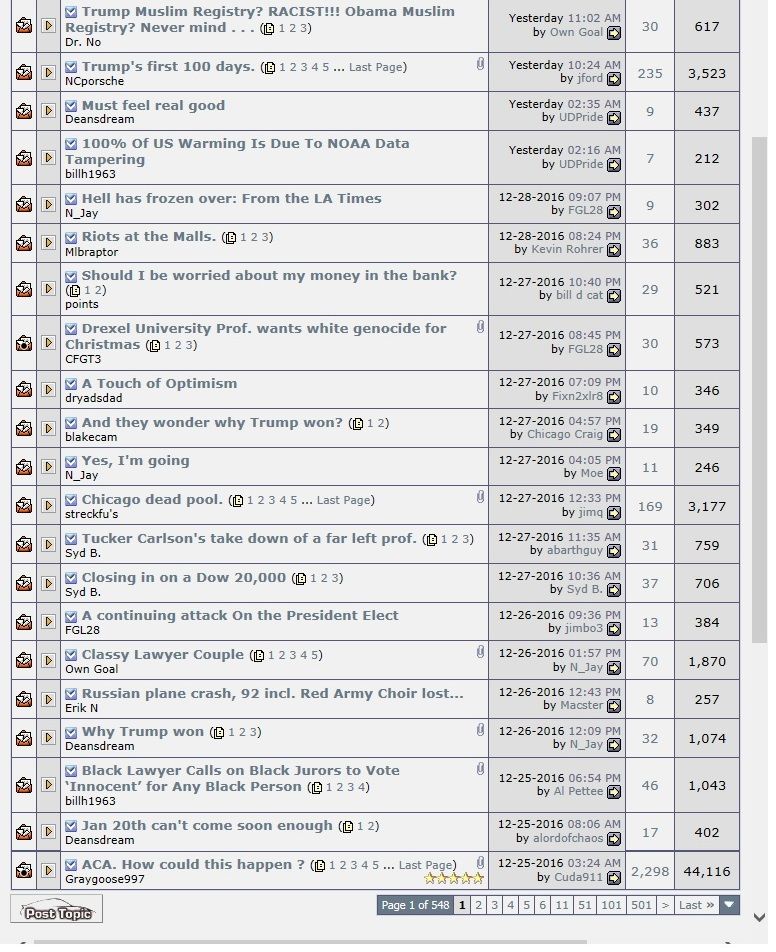

billh1963 at rennlist P&C said:

Another example of how many government agencies are populated by incompetent morons and why many should be scaled back, realigned....

Trump!

http://thefederalist.com/2016/12/30/epa-alaskans-sub-zero-temps-stop-burning-wood-keep-warm/

EPA To Alaskans In Sub-Zero Temps: Stop Burning Wood To Keep Warm

In Alaska’s interior, where it can reach -50 degrees Fahrenheit in winter, the EPA wants people to stop burning wood. But it's just about their only feasible way to stay warm.

In Jack London’s famous short story, “To Build A Fire,” a man freezes to death because he underestimates the cold in America’s far north and cannot build a proper fire. The unnamed man—a chechaquo, what Alaska natives call newcomers—is accompanied by a wolf-dog that knows the danger of the cold and is wholly indifferent to the fate of the man. “This man did not know cold. Possibly, all the generations of his ancestry had been ignorant of cold, of real cold, of cold 107 degrees below freezing point. But the dog knew; all its ancestry knew, and it had inherited the knowledge.”

If only the bureaucrats in Washington DC knew what the wolf-dog knew. But alas, now comes the federal government to tell the inhabitants of Alaska’s interior that, really, they should not be building fires to keep themselves warm during the winter. The New York Times reports the Environmental Protection Agency could soon declare the Alaskan cities of Fairbanks and North Pole, which have a combined population of about 100,000, in “serious” noncompliance of the Clean Air Act early next year.

Like most people in Alaska, the residents of those frozen cities are burning wood to keep themselves warm this winter. Smoke from wood-burning stoves increases small-particle pollution, which settles in low-lying areas and can be breathed in. The EPA thinks this is a big problem. Eight years ago, the agency ruled that wide swaths of the most densely populated parts of the region were in “non-attainment” of federal air quality standards.

That prompted state and local authorities to look for ways to cut down on pollution from wood-burning stoves, including the possibility of fining residents who burn wood. After all, a declaration of noncompliance from the EPA would have enormous economic implications for the region, like the loss of federal transportation funding.

The problem is, there’s no replacement for wood-burning stoves in Alaska’s interior. Heating oil is too expensive for a lot of people, and natural gas isn’t available. So they’ve got to burn something. The average low temperature in Fairbanks in December is 13 degrees below zero. In January, it’s 17 below. During the coldest days of winter, the high temperature averages -2 degrees, and it can get as cold as -60. This is not a place where you play games with the cold. If you don’t keep the fire lit, you die. For people of modest means, and especially for the poor, that means you burn wood in a stove—and you keep that fire lit around the clock.

As Necessary As Food And Water

Growing up in Alaska, I learned this from an early age. (My father, in fact, was a chechaquo. As a white kid growing up in Alaska native villages in the 1950s, the native kids would call him and his siblings chechaquos as a kind of juvenile epithet.) Like many families in Alaska, then and now, we weren’t wealthy and had no other means of staying warm besides burning wood. As kids, my brothers and I would spend long hours stacking cords of wood and, when we were older, felling trees, cutting them into logs, and hauling them back to the house. It wasn’t romantic, it was simply part of life in the far north: firewood was as natural and necessary as food and water.

For most Alaskans, it still is. Replacing wood-burning stoves, especially in the state’s interior, isn’t easily done. Ever since the EPA’s ruling in 2008, local and state efforts to address air pollution caused by wood stoves hasn’t solved the problem. As the editors of the Fairbanks newspaper recently noted, “The borough faces two unpalatable alternatives: More stringent restrictions on home heating devices that could impact residents’ ability to heat their homes affordably, or choosing to stand pat and accept a host of costly economic sanctions and health effects to residents.”

Local residents have been assured that of course the government means well. According to the Times, the EPA official in charge claims that “his agency was definitely not trying to take away anyone’s wood stove, or make life more expensive.” But he also said the EPA’s job is to enforce air quality standards set by the Clean Air Act. The implication is clear: these wood stoves are going to be a problem.

This of course is a ridiculous situation. The EPA has no business telling Alaskans they shouldn’t burn wood to keep warm in the depths of winter. For one thing, concern over air pollution from wood smoke is misplaced. The high levels of particulate matter in places like Fairbanks in January are not the same thing as smog in Los Angeles. The areas affected by pollution from wood stoves are relatively small because they’re the result of something called inversion. At -30 degrees Fahrenheit, smoke doesn’t rise. It drops down to ground level and settles in low-lying areas. But this doesn’t happen city-wide, it happens on a single block or street.

That doesn’t mean people living on that street aren’t affected. But it does mean we aren’t talking about pollution-laced fog descending on an entire city; we’re talking about burning wood to stay warm. If that means you must endure some air pollution from the smoke from time to time, then that’s the price of living in a place like Alaska’s frozen interior. (Full disclosure: I plan to build a cabin in Alaska someday, and I plan to heat it with a wood stove, fully aware that doing so might sometimes subject me to higher levels of particulate pollution. I say it’s worth the risk.)

The problem with the EPA bullying the people of Fairbanks about their wood stoves is that the federal government thinks this is a problem that can be solved. What would the EPA have Alaskans do, use solar panels to heat their homes in winter?

In his story, Jack London wrote of the chechaquo that “The trouble with him was that he was without imagination.” That is, he simply didn’t understand the cold, or where exactly he was:

He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significances. Fifty degrees below zero meant 80 odd degrees of frost. Such facts impressed him as being cold and uncomfortable, and that was all. It did not lead him to meditate upon his frailty as a creature of temperature, and upon man’s frailty in general, able only to live within certain narrow limits of heat and cold; and from there on, it did not lead him to the conjectural field of immortality and man’s place in the universe.

Of the earnest bureaucrats at the EPA fretting over the smoke from Alaskans’ wood stoves in the dead of winter, we might say something similar: they understand facts but not the significance of them. Burning wood when it’s -20 degrees outside will indeed cause the smoke to descend, and breathing such air is admittedly not very healthy. What the EPA doesn’t accept, or even grasp, is man’s place in the universe: in the face of Alaska’s deadly cold interior, there’s only so much we can do. So we build a fire.