Yawkey Center?s invigorating, optimistic effect

New Dana-Farber building puts a beauty mark on Brookline Avenue

Dana-Farber?s new building is the best piece of architecture I?ve seen in Boston?s medical area, a neighborhood that often feels dismal and crowded.

The building?s proper name is Yawkey Center for Cancer Care. But it?s more than that. It?s also the new address, the emblematic front door, for the whole of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute?s cluster of buildings. Yawkey is the outpatient treatment site for the leading cancer center.

There are at least three ways any building can be good. First, it can be a wonderful place to inhabit, to live in or work in, or maybe see a performance in. Second, it can be a beautiful object as viewed from outside, a kind of sculpture, like the Taj Mahal or Hancock Tower. Or third, it can take on the tougher job of helping to shape and invigorate a larger public space.

The Yawkey Center scores well on all three criteria. But it?s the third that matters to the general public. Good cities are made of good streets. Looked at this way, the role of urban buildings is to make the walls that shape the street spaces. Streets are the public rooms in which we spend much of our lives, moving through them as we drive, bus, bike, walk, shop, gather, or just people-watch.

Think of Commonwealth Avenue, where the house facades wear stiff and fancy architectural uniforms and are lined up on both sides like troops on parade. As architecture Commonwealth Avenue is pretty good, but as urban design it?s magnificent. The facades function as the paneled walls of a world class urban room.

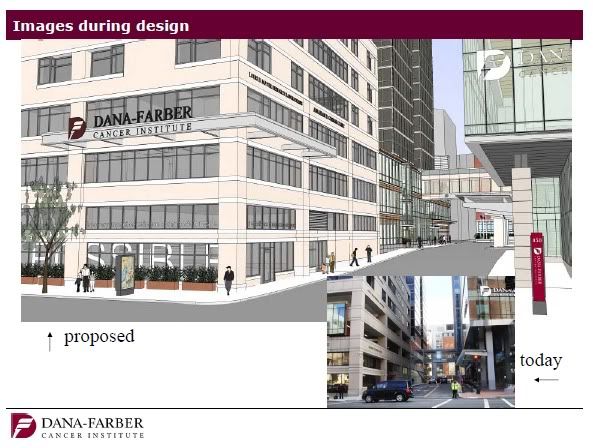

Back to Yawkey. It stands at 450 Brookline Ave., in the middle of the medical area. Brookline is never going to challenge Comm. Ave. as a tourist mecca, but Yawkey gives it a vitality it has never had before.

The design architect was Bob Frasca of the national firm ZGF (formerly Zimmer Gunsul Frasca). The day I visited Yawkey with Frasca, it happened to be raining. All around, large older concrete buildings on the narrow streets were soaking up the rain, turning into the visual equivalent of massive heaps of wet cardboard. Yawkey, by contrast, was looking great. Its materials ? glass, mostly, and panels of reddish terra cotta ? don?t absorb water. The building looked freshly washed.

Yawkey does a lot more than deal well with rain. It?s a big building, 13 stories, yet nothing about it overwhelms the pedestrian. The fa?ade is broken up into a lively variety of shapes, angles, and materials, relieving any sense of massiveness. A few of those shapes have the proportions of floating townhouses, but they never look arbitrary or pasted on. What you see on the fa?ade is always an expression of the different activities that are taking place inside.

Public and private worlds interpenetrate. The sidewalk seems to flow through the glass doors into the entry lobby. Glass canopies reach out to welcome you. Yawkey?s lower two floors are pulled back from the street, creating a wider sidewalk, where a row of planter boxes and trees shield you from traffic. Soon there will be a small cafe, spilling outside with chairs and tables.

At the entry corner, a handsome, boldly graphic signpost stands on the sidewalk like a sentry, flagging your attention and informing you about the building?s activities. A sculpture by artist Howard Ben Tr? is also planned. And there?s a unique place-making feature: a graph inlaid in the sidewalk, depicting the route of the Pan-Massachusetts Challenge bike-a-thon, an annual event that raises money for Dana-Farber.

It?s all simple enough. There?s no egotistic architecture. But taken as a whole, Yawkey succeeds in giving the street an edge of energy and life. Could this be the beginning of a great Brookline Avenue?

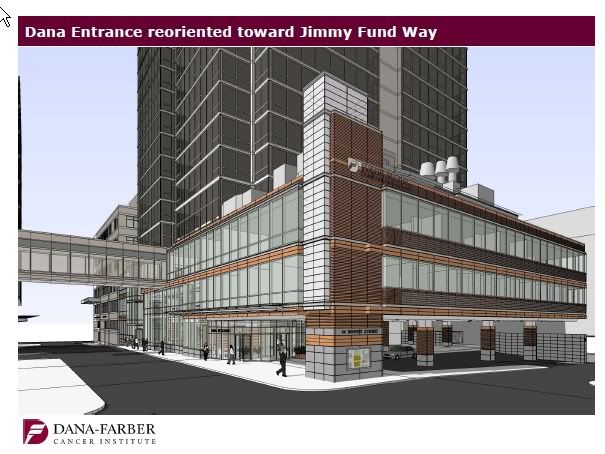

There are seven levels of parking underground, but there?s no vehicle ramp to break the sidewalk. Cars slip quietly up Jimmy Fund Way next door, where they?re greeted underground by valet parking attendants. Valet service is free. When you?re ready to leave the building, you pay your medical bill, and the swipe of your credit card alerts the parking staff down in the garage. They meet you with your car.

I?m pretty much ignoring the Yawkey Center?s interior, which is spacious and thoughtful. There?s a lot of daylight and a lot of warm natural cedar, cherry, and mahogany. Artworks seem to concentrate the atmosphere of air and light, especially an ingenious mobile of birdlike cutouts by Ralph Helmick, a Newton artist.

Like most good designs, the interior was a collaboration. Patients helped choose the chairs and commented on the layout of a mock-up treatment room. Part of the architect?s commitment is to return to the building in one year to perform an evaluation, assessing what?s working and what might need rethinking.

Few buildings this good get built without plenty of money. Yawkey?s total development cost was a hefty $330 million, taken from the $1.2 billion Dana-Farber raised in its last campaign. Boston architects Miller Dyer Spears did preliminary planning and later worked closely with ZGF. Another key player was the Boston Redevelopment Authority, where planners have long sought to improve the public friendliness of buildings in the medical area.

Frasca says he had two goals. One was to give Dana-Farber a visible presence in the city, or as he puts it, ?To plant the flag on Brookline Avenue.?? (In the past, the main entrance to Dana-Farber was on a narrow street at what is now Yawkey?s rear, next to a row of waste containers.) The other aim, he says, was to make ?optimistic?? architecture for this hospital for the seriously ill.

Yawkey proves that even at high densities, in places like the medical area where many buildings crowd into a limited space, it?s possible to build well.

The other lesson of Yawkey is simple. Good cities, as noted above, are made of good streets. The buildings that shape our streets must respond to that imperative.

Robert Campbell, the Globe?s architecture critic, can be reached at

camglobe@aol.com.