Re: W Hotel

[size=+2]Starting slow, finishing fast[/size]

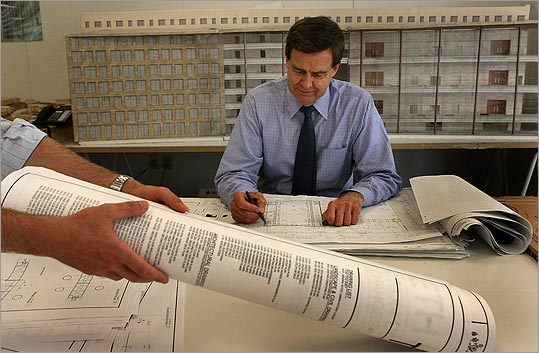

[size=+1]William Rawn?s circuitous route to architecture made him a keen listener - and an award winner[/size]

By Sam Allis, Globe Staff | July 5, 2009

Bill Rawn talks down to you as an equal. Almost 6 feet 8, he glides through a room like an elegant giraffe. You learn when you engage him that he is a listener, not a talker. He absorbs far more than he emits.

It is this listening skill, along with great talent, that has helped make him a stunning success as an architect.

?Listening is a problem for architects,?? Rawn says. ?In architecture school, we do our own projects. There is no client, no budget. You?re doing it all by yourself. You find your own voice, which is good, but you don?t learn to listen to other people.??

Unlike architects with defiant signature styles, he does not design Statements.

?He is modern and contemporary, but not Frank Gehry off-the-wall,?? says Winthrop Wassenar, former director of facilities at Williams College and project manager for Rawn?s ?62 Center for Theatre and Dance which opened in Williamstown in 2005.

Rawn is all listener when he starts a project. He and his associates will spend three days at the site before the design process begins. The firm will set up shop on campus and conduct interviews with students, faculty, administrators. There will be open studio sessions allowing clients of all stripes to follow and comment on the models and sketches. Rawn will repeat this process five or six times.

Last month, Architect magazine named William Rawn Associates, Architects, Inc., the top architectural firm in the country. While all such lists should be treated with skepticism, it?s nicer to be at the top of one than not.

And while the honor is bound to bring him more business, there were no paper streamers on the floor of the sunlit offices above Post Office Square to mark the occasion. Rawn simply maintained his cruising speed - calm, focused, intense - that sets the tone at the 32-person operation.

But then at 66, William R. Rawn III is no secret. He gave us Seiji Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood in Lenox, the soon-to-open W Hotel in Boston?s theater district. His firm has won 81 American Institute of Architecture awards, including nine national honors, since he opened for business in 1983.

He began as a solo act in a tiny office above Tremont Street, much like Philip Marlowe behind a frosted glass door, and since then has completed 138 projects. Fame first came to him in the mid-?80s as the architect-hero in Tracy Kidder?s nonfiction bestseller ?House.?? Kidder provided a blow-by-blow account of how Rawn designed a Greek Revival house for friends near Amherst and then oversaw its construction.

?Bill is pretty amazing,?? says Kidder. ?Architects and builders have a long history of contentiousness, but Bill got along fine.??

No one quite knows how to describe Rawn the architect. You hear the words ?elegant?? and ?understated?? a lot. Some call him conservative, but compared to what? He is no hidebound proponent of red brick. He prefers the word ?contemporary,?? and that sounds right.

?I?ve given up things?

By today?s standards, when balance in life is supposed to be the key to happiness, Bill Rawn is a failure.

He works deep into the evening five days a week and then repairs on weekends to his place in Provincetown to read, swim, and regroup. He calls this balance, but few others would.

During the week, he spends close to three hours at the end of each day with his two partners, Clifford Gayley and Douglas Johnston, discussing projects and architecture in general. (He always says ?we?? rather than ?I.??) Then he?ll usually continue working after that.

?Without those extra hours, we would not be where we are today,?? Rawn says. ?These are the demands of a professional life. And we try hard to get everything 97 or 98 percent right.??

This schedule has cost him, but he?s comfortable with the arrangement. ?I?ve given up things,?? he concedes. ?I don?t have as many close friends as I want. I lose tertiary friends. Close friends visit me at the Cape on weekends.??

More often than he?d like, he finds himself giving up the season tickets to the Boston Symphony Orchestra that he has held in the second balcony for 30 years. ?A movie??? he says. ?That?s two hours out of my life.??

Rawn?s path to architecture was a curious one. Born in Berkeley, Calif., and raised among the leafy streets of San Marino, outside Los Angeles, he put out his own little newspaper for a few years starting when he was 12. He graduated from Yale in 1965 as a political science major and then ended up at Harvard Law School, of all places. He practiced law for two years in Washington and then bowed out of the field.

How did the experience influence his architecture? Not a whit.

What did change his life were the four years he spent as assistant to the president and then assistant chancellor for physical planning at the University of Massachusetts Boston. This experience led him to the MIT School of Architecture + Planning.

It was at UMass that he honed his listening skills. ?I learned to listen to neighborhood groups,?? he says. ?I learned that those community groups knew what they needed more than I did.??

Rubbing shoulders

Today, Rawn is the go-to architect by elite colleges and universities for performance centers and dormitories. What he is most proud of are his repeat clients, such as Dartmouth, Williams, Swarthmore, and MIT.

His buildings are easy on the eye, and they wear well. He incorporates natural light whenever he can with extensive use of glass. Many of his buildings are LEED certified (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) for environmental sustainability. In renovating an ancient swimming pool building at Bowdoin into a recital hall, he used a geothermal system to heat and cool the place.

Rawn refuses to name his favorite work, but Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood, summer home of the Boston Symphony, comes up most often. Opening in 1994, it was the breakthrough project that catapulted him into the first rank of American architects.

The hall is known for its soft, convex roof and the gorgeous interior use of Alaskan yellow cedar, teak, and Douglas fir. There?s the giant door in the rear of the building that opens to a grass slope and magnificent view. At night, the space glows from the outside. Acoustically, it is ranked the second-best music hall built in America in the last 50 years.

Rawn is always consumed with details, but he outdid himself with Ozawa Hall. He and his staff spent two hours one day on the Boston Common rolling wine glasses down a grass hill to learn at what angle they would remain upright. He envisioned picnics on the Tanglewood grass for those sitting outside and wanted to make sure they could put a glass down in safety.

His range locally includes the West Campus at Northeastern University, fronted by the shimmering Building H along Huntington Avenue, which won the 2005 Harleston Parker Award as the most beautiful building in Boston. In October, his huge new Cambridge Public Library will open. Also opening this fall is the 26-story W Boston Hotel and Residences, for which he was the lead architect in conjunction with Jung|Brannen.

Elsewhere, he garnered high praise for his theater at Williams and for The Music Center at Strathmore in Bethesda, Md. the second home of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra that opened in 2005. But his range extends to a horticultural center at Mount Auburn Cemetery, a synagogue in Wellesley, a federal courthouse in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and a luminous little fire station in Columbus, Ind.

What do they have in common? Rawn is a design democrat with a small ?d?? who likes to put people from all walks of life close together, ?rubbing shoulders,?? as he puts it. Things can get tight, as in the Williams theater lobby, which is fine with him. He believes in density.

Civically engaged

Rawn has been deeply involved in Boston?s urban design for two decades. He remains the last of the first crop of members of the Boston Civic Design Commission, created in 1989. The BCDC advises the Boston Redevelopment Authority on new real estate projects and their impact on the city. He?s good at it, and his opinion is prized.

When he looks back at all he?s brought to Boston, Rawn speaks with great affection about the three affordable housing projects he designed here early in his career.

They were 20 units of row houses near Andrew Square, another 50 in the Charlestown Navy Yard, still another 165 in the area behind Mission Hill, all done for the international bricklayers and masons union. The Navy Yard project won him his first AIA national award.

The goal, he says, was to design a long, strong building in keeping with the ones leading to the water elsewhere in the yard. Yet he wanted to make clear his building was a modern one, so he applied two-tone brick stripes along the exterior. He notes proudly that 47 of the 50 units have a water view.

?We worked busily trying to upset the apple cart,?? he says.

His career flourishing, Rawn points out that architects reach their peak in their 50s and 60s. Or older. Frank Lloyd Wright was over 80 when he designed the Guggenheim Museum in New York. It takes years of experience to learn what works and what doesn?t, to be ready for big projects.

So what?s next for Bill Rawn? ?I will always be open to new building types,?? he says, referring to the Mount Auburn project and the synagogue in Wellesley.

At the top of his wish list is a museum. He has never been approached to design one. Whatever he pursues, the man will continue to do what he does best: listen.

Sam Allis can be reached at

allis@globe.com.

For a gallery of his Rawn's work, http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_arts/gallery/rawnonline/